Cyclopedia (6 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

BOBET, Louison

Born:

St Méen le Grand, France, March 12, 1925

St Méen le Grand, France, March 12, 1925

Â

Died:

Biarritz, France, March 13, 1983

Biarritz, France, March 13, 1983

Â

Major wins:

World road race, 1954; Tour de France 1953â55, 11 stage wins; King of the Mountains 1950; MilanâSan Remo 1951; Tour of Flanders 1955; ParisâRoubaix 1956; Giro di Lombardia 1951; BordeauxâParis 1959

World road race, 1954; Tour de France 1953â55, 11 stage wins; King of the Mountains 1950; MilanâSan Remo 1951; Tour of Flanders 1955; ParisâRoubaix 1956; Giro di Lombardia 1951; BordeauxâParis 1959

Â

Nickname:

the Baker of St. Meen

the Baker of St. Meen

Â

Further reading:

Tomorrow We Ride

, Jean Bobet, Cordee, 2008

Tomorrow We Ride

, Jean Bobet, Cordee, 2008

Â

First man to win the TOUR DE FRANCE in three consecutive years (1953â55); the Breton was a tenacious cyclist who learned his trade alongside FAUSTO COPPI in Italy and was also capable of major one-day wins such as MILANâ

SAN REMO (1951), the TOUR OF LOMBARDY (1951), PARISâROUBAIX (1956), and the world road title (1954).

SAN REMO (1951), the TOUR OF LOMBARDY (1951), PARISâROUBAIX (1956), and the world road title (1954).

Bobet is also famous for a curious episode in the 1955 Tour when he refused to put on the yellow jersey because it was made of synthetic material; he was worried it might irritate his skin. Perhaps his nerves were understandable: he completed the Tour with a severe saddle boil, which was operated on after the race; he came back to competition too soon and was never the same again (see SADDLE SORES for other nether nasties).

Bobet was celebrated for his determination and ended his career with perhaps the bravest final act cycling has seen. In the 1959 Tour he was ill and suffering but forced himself to complete much of the race, finally riding to the top of the highest pass in the event, the Col de l'Iséran (see ALPS to find out how high and hard this one is relative to other

cols

). There he climbed off his bike, never to race again.

cols

). There he climbed off his bike, never to race again.

BONESHAKER

Generic term for early front-wheel bicycle similar to the machines invented in 1861 by the Frenchman Pierre Michaux and his son Ernest, not dissimilar to the DRAISIENNE, but it was powered by pedals on the axle of the front wheel, “like the crank handle of a grindstone” as Pierre put it; in 1865 his company turned out 400 of the things in their workshop near the Champs-Elysées. They were unforgiving and hard to steer, but they were also simple to use and speedy compared to walking.

Generic term for early front-wheel bicycle similar to the machines invented in 1861 by the Frenchman Pierre Michaux and his son Ernest, not dissimilar to the DRAISIENNE, but it was powered by pedals on the axle of the front wheel, “like the crank handle of a grindstone” as Pierre put it; in 1865 his company turned out 400 of the things in their workshop near the Champs-Elysées. They were unforgiving and hard to steer, but they were also simple to use and speedy compared to walking.

Michaux understood the value of publicity; he supplied a bike to the French head of state Napoleon III and supplied JAMES MOORE with one for the first official cycle race in 1868. With some outside investment from Olivier Brothers, his company pushed up production to 200 a day; there were by now 60 other boneshaker makers in the capital and upmarket models were being

made with steel frames, ebony wheels, and ivory grips on the handlebars.

made with steel frames, ebony wheels, and ivory grips on the handlebars.

In November 1869 the first cycling magazine,

Le Vélocipede Illustré

, and Olivier Brothers ran the ParisâRouen race, won by Moore (see ROAD RACING) using the machines. By now race meetings were drawing up to 300 competitors, including women, and as many as 10,000 spectators. The vogue for the machines spread rapidly, to Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Britain, and the US. In France, however, velocipede use stuttered with the onset of the FrancoâPrussian war in 1870, and the political turmoil that followed.

Le Vélocipede Illustré

, and Olivier Brothers ran the ParisâRouen race, won by Moore (see ROAD RACING) using the machines. By now race meetings were drawing up to 300 competitors, including women, and as many as 10,000 spectators. The vogue for the machines spread rapidly, to Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Britain, and the US. In France, however, velocipede use stuttered with the onset of the FrancoâPrussian war in 1870, and the political turmoil that followed.

In Britain the Midlands, and Coventry in particular, rapidly became the center for velocipede production. Gradually, the design changed: the unpowered back wheel of the Michaux-type machines was shrunk, to save weight, frames became more nimble, and the front wheel grew, to a limit set by the inside leg of the rider. The boneshaker disappeared, and the HIGH-WHEELER was born.

BOOKSâFICTION

A subjective selection in no particular order

Â

The Wheels of Chance

, H.G. Wells

, H.G. Wells

Hard-to-find turn-of-the-century novel in which Wells's hero, Hoopdriver, undertakes a 10-day cycle tour of Britain's South Coast and falls in love with a fellow cyclist, one of many women given freedom by their newfound mobility. Beautiful portrait of cycling in the formative years of the pastime, with acute observation of the blurring of class distinctions the bicycle brought with it.

Â

Cat

, Freya North

, Freya North

Since its publication in 1999 this chick-lit tale of bedhopping on the Tour (as the author puts it, “big egos and bigger bulges in the lycra shorts”) is probably the biggest selling cycling fiction work ever: 10 years later, almost every British thrift store and teenage female babysitter seem to have a copy. Tour journos who were on the 1998 race when La North was researching the work are known to scrutinize the book closely trying to figure who is who. Trivia lovers note: there is a William Fotheringham in the pages, but he's sports editor of the

Guardian

. We emphasize that it is fiction.

Guardian

. We emphasize that it is fiction.

Â

Bad to the Bone

, James Waddington

, James Waddington

Surreal novel published by happy coincidence in 1998, the year of the Festina scandal, in which top cyclists in the TOUR DE FRANCE are offered a Faustian pact by a sports doctor: a wonder drug which will make them unbeatable, but which has horrendous side effects. It's fiction. Honest. Pro cyclists would never go so farâwould they?

Â

The Rider

,

Tim Krabbe

,

Tim Krabbe

Cult novella with a popular English translation from 2002. Goes inside one rider's mind during a fictional race somewhere hilly in the South of Franceâthe only issue being that if any cyclist actually thought that much he'd be too

distracted to compete. Totally compulsive: you either love it or it leaves you cold.

distracted to compete. Totally compulsive: you either love it or it leaves you cold.

Â

The Yellow Jersey

, Ralph Hurne

, Ralph Hurne

Possibly the least politically correct cycling work ever, what with the big-breasted, topless lady (alongside the Condor bike) on the Pan paperback, and the constant references to potential sexual partners as “it.” Get past that and this 1973 novel is a hilarious, racy, suspenseful gem: you can't help but get drawn in as Terry Davenport,jaded ex-pro and womanizer, gears up for one last Tour and suffers like hell in the process. The bit where the top five riders in the race all test positive is amusingly prescient. Written with two endings, one for the British market, one for the US.

Â

The Big Loop

, Claire Huchet Bishop

, Claire Huchet Bishop

Published in 1955, offering a Parisian teenager's view of a cycling career from aspirant without a bike to Tour winner. It has a certain charm as a portrait of French cycling in the glory days of Bobet and Robic, but is unlikely to cut much ice with the PlayStation generation.

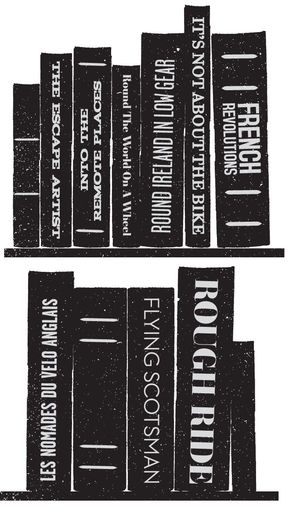

BOOKSâNONFICTION

The Great Bike Race

, Geoff Nicholson

, Geoff Nicholson

Masterly history of the Tour de France crafted around the 1976 race, oozing humor and glorious detail without a hint of self.

Nicholson, God rest his soul, was a writer who topped the Galibier while the others were toiling up the Télégraphe. His sequel,

Le Tour

, did not quite hit these heights.

Le Tour

, did not quite hit these heights.

Â

Wide-Eyed and Legless

, Jeff Connor

, Jeff Connor

No journalist will ever get as close to a team as Connor got to ANC-Halfords in the 1987 Tour de France, and no squad will want them to, given the stuff he picked up thanks to his inimitable eye for detail. The gradual implosion of the first British trade team to ride the Tour is dissected in all its quarrelsome, anarchic glory. Connor's attempt to ride a Tour stage is the hilarious high point.

Â

Lance Armstrong's War

, Daniel Coyle

, Daniel Coyle

The best way to learn about LANCE ARMSTRONG and 21st century pro cycling, through the eyes of a wry outsider given inside access to Planet Lance. Brilliantly observed, hilariously written, but above all dispassionate, neither for nor against the controversial Texan.

Read and judge Le Boss for yourself.

Â

Major Taylor

, Andrew Ritchie

, Andrew Ritchie

Ritchie set the standard for cycling biography with this account of the life of one of America's first nonwhite sports stars. Impeccable research and a lively re-creation of cycling's HEROIC ERA.

Â

Kings of the Road

, Robin Magowan and Graham Watson

, Robin Magowan and Graham Watson

This 1985 opus is the best integrated words-and-pictures book about professional cycle racing. Some of the content is dated but GRAHAM WATSON's photos and the pen-portraits of ROBERT MILLAR, SEAN KELLY, PHIL ANDERSON, and GREG LEMOND are timeless.

Â

Kings of the Mountains

, Matt Rendell

, Matt Rendell

Exhaustive and intense investigation into cycling in COLOMBIA. Like Ritchie's

Major Taylor

, it extends way beyond things two-wheeled and offers a superb insight into a controversial, colorful nation.

Major Taylor

, it extends way beyond things two-wheeled and offers a superb insight into a controversial, colorful nation.

Â

Greg Lemond: The Incredible Comeback

, Samuel Abt

, Samuel Abt

The best work from one of the great cycling writers of the last quarter-century. This 1990 account of LeMond's return from near-death to win the best Tour de France ever is as good at it gets.

Â

Sean Kelly: A Man for All Seasons

, David Walsh

, David Walsh

The definitive account of the great man's rise in the early 1980s; Walsh is superbly observant, can work out the deals his fellow Irishman is striking, and benefits from unlimited access. Those were the days.

BOOKSâMEMOIRS/AUTOBIOGRAPHY

It's Not About the Bike

, Lance Armstrong

, Lance Armstrong

Love or loathe Lance Armstrong, you can't ignore one of the biggest-selling cycling books ever, because of the visceral emotions it brings. The detail is telling, most notably the scene where Armstrong has to masturbate into a cup so that he can bank sperm before his testicular cancer operation. A key element in the Big-Tex myth.

Â

Flying Scotsman

, Graeme Obree

, Graeme Obree

For my money the rawest and best cycling autobiography. Graeme Obree tells his story uncut, without the intermediary of a ghost writer, and tells of sexual abuse and attempted suicide with not a hint of self-pity. Alongside this the film of the same name is distinctly insipid.

Â

Rough Ride

, Paul Kimmage

, Paul Kimmage

As with Armstrong, you swoon or swear at this up and (let's face it, mainly) down account of Paul Kimmage's career as a pro in the mid-1980s. Great inside stuff, but his drug “revelations” seem timid now, though at the time they were scandalous. No one describes suffering on a bike quite so well; brutally debunked the “glamour” of pro life, even if it is a bit Gone with a Whinge.

The Escape Artist

, Matt Seaton

, Matt Seaton

Elegiac telling of Matt Seaton's discovery of cycling against a background of serious “stuff of life,” namely his wife's death of cancer. Beautifully written, elegantly crafted, tugs at the heartstrings, and sums up why we all ride bikes.

Â

A Dog in a Hat

, Joe Parkin

, Joe Parkin

The life and times of a mediocre American pro in Belgium is one of the most compelling memoirs of its time, mainly because of Parkin's sheer love of Flandrian cycling culture and the pure weirdness of pro racing. The high point comes early on, when Parkin reads the lyrics to “Jumping Jack Flash” handwritten on Bob Roll's tires.

Other books

Promise by Dani Wyatt

Fangtabulous by Lucienne Diver

WhiteSpace: Season One (Episodes 1-6 of the sci-fi horror serial) by Platt, Sean, Wright, David

The Cold Beneath by Tonia Brown

A Flame Run Wild by Christine Monson

Hostile engagement by Jessica Steele

Fabled by Vanessa K. Eccles

The Extinction Switch: Book three of the Kato's War series by Broderick, Andrew C.