Damn His Blood (30 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

For Peel a murder

9

case was to be treated and examined carefully before any speculative conclusions could be made. He had a tidy administrative mind. ‘There is nothing like a fact,’ he declared in 1814, a theme he returned to two years later, when he reaffirmed his belief that ‘facts are ten times more valuable than declamations’. These views were entrenched in his political philosophy, and for William Smith they would be a stumbling block. Smith’s letter had declared much but proved nothing. To Peel at the Home Office it appeared amateurish, hasty and speculative, traits that he instinctively shied away from and qualities that he was actively trying to dispel from England’s policing system.

About four months earlier, on 29 September 1829, Peel’s police force – the first of its kind in England – had been deployed in parishes within a 12-mile radius of Charing Cross in London. Four months on, Peel was still caught up in the introduction and workings of the new body, which had faced stiff opposition and contempt from the beginning. The policemen, dressed in blue, were derided as spies and snitches and – worst of all – a standing army released onto the streets of the capital. An unflattering crop of nicknames had arisen in the few months since Peel’s police had been operational. Peel’s Bloody Gang, the Plague of Blue Locusts, the Blue Devils and Raw Lobsters were all insults circulating in the streets and printed in the newspapers.

fn1

But for Peel the introduction of such a body was a necessity in a rapidly developing society in which crime, so he argued, was rising sharply. He considered the old system of policing, which had its roots in the Middle Ages, unfit to deal with the challenges posed by innovative nineteenth-century felons. In a society where criminals could make use of swift modes of travel and fast transmission of information, there needed to be a trained, professional force that was equal to them. Peel’s police were to be a disciplined and effective tool of the state in this new modern age. They were expected to react to crime intelligently, to protect and pursue.

This was the climate in which Smith’s letter from Worcester was received. And for Peel in Whitehall it contained several flaws. First, although it appeared the skeleton belonged to Heming, there was no firm proof that this was the case. For a positive identification to be made a new inquest would have to be held, and after the passage of so many years it was uncertain that the bones could be shown to be Heming’s. Second, Peel was more accustomed to corresponding with magistrates, whose role it was to investigate cases and apply to the Home Office for support. He was not just a man of detail but also a man of form, and to receive a request for the royal pardon from a coroner was irregular and an example of just the type of unregulated procedure that annoyed him.

In his reply the home secretary mingled inquisitiveness with non-commitment. He assured Smith that he understood both the gravity and significance of his letter, but he implored him to investigate the matter further. Peel ignored the coroner’s request for a royal pardon entirely and instead asked Smith to keep him abreast of any further developments, pointedly asking for the name of the local magistrate at Oddingley. It was a typical, ponderous response.

While Peel remained sceptical, others took far less convincing. By 24 January reports of Burton’s find were sweeping across Worcestershire. It was a news report like no other, as if a story had been plucked deliciously from the past to tantalise imaginations and set conversation alight. Those under the age of 25 would have only known the tale through local rumour or taproom gossip; for the older generation it would have been a misty memory, jumbled with other tales from the war years. Others who remembered Parker’s murder well were now among the elderly and many of those directly involved in the manhunt were dead. Everyone, though, now returned to the story afresh and conjecture flared. Was this second killing the work of a single man or a band of murderers? How many of those implicated were still alive? Would they be finally brought to justice?

Following the exhumation, Pierpoint had spent Saturday evening at his home carefully reassembling the skeleton to complete a more detailed analysis. By Sunday morning he was able to present Smith with a list of further observations. Once again they matched Heming’s profile. Without doubt, Pierpoint said, the bones were those of a man aged between 30 and 50 years of age. Having examined the fracture on the forehead more closely, he now declared the skull to have been shattered into twenty or more pieces. It was a fearsome injury, he said, ‘quite sufficient to produce instantaneous death’.

11

Although Pierpoint was sure that the man had been bludgeoned, he had no idea what kind of weapon could have caused such fractures. He told Smith that it must have been something very blunt and heavy but was certainly not a pistol, as the coroner had initially speculated. He was also sure that it was not a self-inflicted wound, which ruled out suicide. To cause such an injury several blows would have been required. It was murder, of that he was certain.

As Matthew Pierpoint continued with his assessment of the skeleton, in the villages and towns that surrounded Worcester, Droitwich and Oddingley rumours started to circulate. It was well known that at the time of Heming’s disappearance Thomas Clewes had been the master of Netherwood Farm. Clewes had cursed Parker with Evans and Barnett in the months before the murder. He had been seen at Heming’s home in Droitwich, and his subsequent troubles with money and alcohol were well documented. That a grave could be concealed at Netherwood without Clewes’ knowledge or approval seemed impossible.

Within days the newspapers were speculating, too. They focused their attentions on the barn, hoping that a careful description and analysis of the structure or the identification of an unusual feature might expose another of its secrets.

Berrow’s Worcester Journal

dwelt on the geography of the fold-yard, ‘the spot chosen for the grave

12

being close to a pool which received the drainings of the fold-yard, appears to have been selected in the expectation that its contiguity to the pool would hasten the decomposition of the body’.

The use of ‘selected’ lent an eerie note of premeditation to the piece. To dispose of the body in the dampest corner of the barn demonstrated either a thorough knowledge of the farm, or sheer good luck. That Thomas Clewes must have been involved was also inferred by Charles Burton, who noted that access to the barn came from two strong double doors. The pair in the fold-yard were secured by a padlock, he said; the others opened out into the bridle path and were held shut with a strong wooden pole. Burton argued that nobody could have entered the barn without first acquiring the key, which, Henry Waterson explained, was always kept in the house.

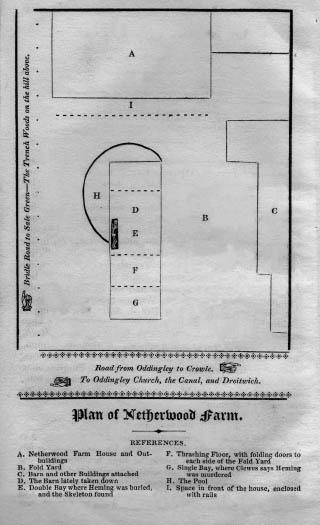

On Sunday 24 January the number of curious locals who wandered into frozen Netherwood Lane to see the site for themselves rose from a steady trickle to a small crowd. The farm was surrounded by snowy meadows that behind the farmhouse sloped gently upwards towards Trench Wood, where Thomas Clewes now lived with his family. But Clewes was not yet the object of their attentions. Instead they looked at the small damp plot where the barn had so recently stood. The building had been rectangular, a little over 20 yards by four across, and split into three distinct sections: a single bay at the front, a threshing floor in the middle and at the rear a large double bay. It was in this part of the barn that the skeleton had been found, not ten seconds’ walk from the farmhouse door.

Like Parker’s glebe, Netherwood’s barn had become a place of horror, its very ordinariness lending it a disturbing quality. But while the skeleton suggested much, it proved very little. In his office at Worcester this fact was troubling William Smith, who had thrown all his energies into arranging an inquest. For twenty-three-and-a half years secrets had festered beneath conversations just as the bones had been hidden beneath the ground. Almost all attempts to extract the truth had been met with blank denials and stony faces. Now, though, things felt different. Smith hoped the skeleton would prove more than a wondrous find, a cause of fantastical imaginings in the parishes and the newspapers, but rather a catalyst to loosen unwilling tongues.

Smith consulted Pyndar’s notes and began to draw up a list of all of those involved, however slightly, in the events of 1806. Thomas Clewes, the previous master of Netherwood Farm, was his first name, but also on the list were John and William Barnett, both of whom were still farming in the parish. He also wrote to Elizabeth Newbury, John Rowe and John Perkins, and began a search for the two butchers – Thomas Giles and John Lench – who had disturbed Heming in Parker’s glebe over two decades before. Smith invited each of these individuals to Worcester the following Tuesday morning, where a second inquest would commence – this time on the Netherwood skeleton. Several men, though, would elude the coroner’s summons. One of them, by just seven months, was Captain Samuel Evans.

fn1

Raw lobsters are generally blue, the colour of the police uniform. But when placed in boiling water they turn red, the colour of the army tunic.

CHAPTER 14

Extraordinary and Atrocious Circumstances

Worcester, 25–31 January 1830

AT A QUARTER to eleven on the morning of Monday 25 January, a clear, frosty winter’s morning with the remnants of a new moon fading in the sky above, William Smith prepared to open the inquest on the Netherwood skeleton at the Talbot Inn in Worcester. The Talbot lay near the end of a little row of pleasant Georgian houses which lined the Tithing, a long thoroughfare that snaked from the north into the city centre towards the cathedral. It was an impressive hostelry, an elegant assembly of gleaming red brick, ancient beams and pretty dormer windows. It stood three storeys tall and was lit from the outside by the glow of two gas lamps that arched imperiously over its oak entrance door.

Smith had considered Oddingley an unsuitable location for the inquest. Not only was it a small parish and therefore ill equipped for the anticipated influx of visitors, but it seemed improper to continue the investigation in a place which for so long had shielded the truth. As a statement of intent, Smith had taken the unusual step of drawing the inquiry out of the village and forbidding Oddingley parishioners from serving on the coroner’s jury. Instead the evidence was to be laid before 23 men from the surrounding area: six from Crowle, six from Claines, four from Tibberton and the remaining seven from Himbleton. Like any parish, Oddingley was accustomed to administering its own business. Now it would be judged by its neighbours.

Long benches had been pulled across a large room to the rear of the building, which jutted back into the stable yard. The makeshift courtroom was filled with Oddingley men, many of them familiar to one another yet this time drawn together in an unusual environment. There was Thomas Clewes and the two Barnett brothers. Charles Burton was there along with other farmhands – James Tustin, William Chellingworth and George Day, Parker’s old tithe boy. The occasion had the air of a reunion, nearly a quarter of a century having passed since the events they had been summoned to recall. There was also a hint of paradox. Smith was about to stir memories of a warm and lively June afternoon in Oddingley’s airy fields in the cold bleak atmosphere of a city courtroom. The witnesses were not wearing smock frocks, but were wrapped tightly in thick greatcoats and over-cloaks, warm breeches and riding boots. At the head of the room the coroner and his jury huddled about a long rectangular table. The skeleton, now cleaned and glimmering brightly in the dim light, lay like a macabre trophy before them.

A plan of Netherwood Farm in January 1830. Published by E. Lees, an innovative Worcester printer

The jury was sworn in at 11 o’clock. Smith welcomed the men to the inquest and invited them to examine the bones. Then the first witness was called. Charles Burton narrated his movements over the past month and explained how he had discovered the skeleton ‘on Thursday last’. He told the jury that Heming was his brother-in-law and he suspected the shoes found belonged to him. The shoes were exhibited, and Burton was asked whether he recognised them. ‘These shoes now produced are as near as the size of Heming’s as possible. I believe them to have been his,’ Burton replied.

Burton’s evidence was illuminating and precise, but at times it was also faintly speculative, as if he had already settled on his own theory. When a plan of the barn was produced and he was asked to indicate the location of the skeleton, he did so, pointing to the double bay while repeating several times that the barn was situated ‘near to the house’.