Damn His Blood (46 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

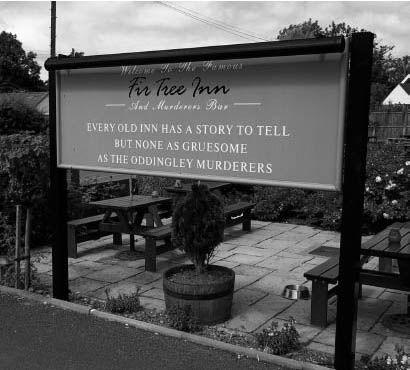

The story as remembered today at the Fir Tree Inn in Dunhampstead, on the edge of Oddingley parish, where Thomas Clewes was once the landlord

Artefacts from the Oddingley case have dispersed, some of them into public libraries and others into private collections. The Fir Tree Inn in nearby Dunhampstead, where Thomas Clewes once served as landlord, displays a shrine to events. There is a ‘Murderers’ Bar’ replete with a flintlock shotgun hanging malevolently from a beam, a copy of one of the ballads, a parochial map and a black and white photograph, supposedly of the tithe barn. Outside a sign stands in the car park: ‘Every old inn has a story to tell but none as gruesome as the Oddingley murderers.’ The history has been harnessed well here, yet the shotgun is not the murder weapon. That has long since disappeared, last sighted in the hands of Richard Barneby in 1830. Also vanished without trace are Richard Heming’s bones and James Taylor’s blood stick, both of which were last displayed publicly at the Guildhall in 1830.

For more than a century local researchers have returned to the story, drawing out details and lingering on the finer points of the case. One of these was Reverend Sterry-Cooper, who lived and worked in Droitwich in the first half of the twentieth century. On 14 July 1939 Sterry-Cooper received a letter from Captain Berkeley. ‘I am 75¼, I am probably near the end,

1

but must show you the site of the robber’s cave (now a hole) in the Trench Wood,’ he urged. Ten years had passed since Berkeley had ventured into the wood, and when Sterry-Cooper joined him to search the following week it was without success. The den

Berrow’s Journal

had described so eagerly in 1805 had gone, either overgrown or filled in, and over the next decade it would be followed by much of Trench Wood, which was clear-felled during the 1940s, with many oak, elm and ash trees being replaced by other species designed to yield quick timber for paintbrush and broom handles.

Sterry-Cooper’s interest, though, extended beyond Trench Wood: he delved into details of the tithe dispute and explored the finer points of law. The clergyman hoped to prove that the Oddingley case was a catalyst for the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836. This was a grand thesis and difficult to justify, but it brought Sterry-Cooper back to Oddingley again and again. On these visits he befriended locals, scribbled notes and, intriguingly, produced a set of atmospheric, grizzled black and white photographs which now provide something of a window into the village’s past.

In one picture there stands the ghostly figure of a matriarch, hands on hips, outside Park Farm. She glares into the lens suspiciously from a distance of 15 yards. The brick farmhouse, several barns and a little slatted wooden fence stand behind her, but the picture still feels sparse and lonely. Another is taken on a dry winter’s day at the village crossroads. A girl stands pencil-straight on the verge outside Pound Farm; a spry terrier dances at her feet. In the background the hedgerow is neatly trimmed and the half-timbered farmhouse stands proudly, its three great chimney stacks rising high into the sky. It was a century since the Barnetts had given their orders in the fold-yard, and in that time the property had shifted from farmhouse to poor house then back into private ownership. At one point the building also served as the village inn, being known as the Bricklayer’s Arms. During this time a cryptic warning hung from its sign: ‘Blazing fire, here lies danger. A friend must pay as well as a stranger.’

Pound Farm in the 1930s, taken by Reverend Sterry-Cooper.

2

The farm is almost unchanged from how it was a century earlier when Barnett and Parker clashed in the fold-yard

Sterry-Cooper’s photographs give one of the earliest glimpses of Oddingley, an empty place of wizened oaks, overgrown gardens, abandoned buildings and outhouses. There are only fleeting traces of the farmhands, dairymaids, shepherds and drovers and there is little sense of action, movement or purpose. There’s an elusive quality that seems to befit the Oddingley story, where the complete picture is always obscured. In the years after the trial, the nineteenth century would come into sharper focus with a new-found thirst for statistical data and record-keeping, and the invention of photography. From 1841 onwards, increasingly detailed censuses recorded more facts than ever before about the lives of British subjects. The landscape was captured, too, by a wave of tithe commissions that trawled the country in the 1840s, noting down the names of buildings, fields, woods, hills, roads and streams. The Oddingley Murders languish in the shadows of nineteenth-century history, just before this new modern age. Only the single untrustworthy woodcut of Parker and Heming remains, and there are no pictures of Clewes, Barnett or Banks. When he died in 1850, Robert Peel would be the last prime minister not to be photographed. Like Sterry-Cooper’s black and white images of Oddingley in the 1930s, the surviving documents suggest much but they don’t reveal all.

In the nineteenth century the Oddingley case had a long afterlife. Nine months after the assize trial finished

The Age

magazine included the story in its annual round-up, alongside the accession of William IV and the eruption of Mount Etna. A decade on, in 1842, Erskine Neale’s

The Bishop’s Daughter

was published, and later in the century Theodore Galton wrote

Madeline of St Pol

. Both fictionalised retellings of the story which drew on the authors’ local connections and knowledge. Thomas Hardy, a habitual note-taker, included a nimble description of the Oddingley affair among his research papers: ‘Murder of clergyman planned by several villagers,

3

because he was obnoxious to them by rigid manner in wh. he exacted his tithes &c. Murder carried out by one named Heming. Heming soon after disappears – It is found years after that a reward being offered the planners feared H wd. not stand it & murdered him in barn – Skeleton found there, a 2ft rule beside it. He was a carpenter.’

But as the century wore on, Britons busied themselves with a fresh set of horrible yet fascinating crimes. George Orwell would later describe the second half of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth as an ‘Elizabethan Period’

4

in English murder, citing the cases of Dr Palmer the Rugeley Poisoner, Jack the Ripper, Dr Neill Cream and Dr Crippen as examples. And as each new case emerged, its details were reported in increasingly intense and complex ways by a more professional press, whose coverage had evolved to include photographs of suspects, victims, crime scenes and crowds – jeering, hissing or sobbing – outside the courtroom.

These fresh scandals and sensations overtook the Oddingley affair, which dwindled into shy obscurity in the early years of the twentieth century, a position it has retained ever since. And even when set beside contemporary stories like the Ratcliffe Highway Murders, John Thurtell, the Red Barn Murder and, at a stretch, Eugene Aram, it feels somehow lost, often absent from period articles or anthologies of nineteenth-century crime. Perhaps because no one was ever successfully prosecuted for either murder – most sensational criminal investigations concluded with an execution, a climactic moment in the arc of the story. The Oddingley case did not.

Long into the nineteenth century thousands of spectators of all classes gathered to witness the execution of a murderer. An estimated 7,000 turned up to see William Corder hanged in Suffolk in 1828 and an enormous assembly of between 30,000 and 50,000 watched the final moments of the notorious Frederick and Maria Manning at Horsemonger Lane in Southwark in 1847. On these occasions a diverse and fantastic array of memorabilia was offered for sale, including scraps of the hangman’s rope, pieces of the condemned felons’ clothes, transcripts of their last confessions and even, on special occasions, limited-edition medallions struck by enterprising local mints. In high-profile cases a second wave of mementos would follow the first: engravings of the scene, public waxworks and death masks and other macabre relics from the anatomised bodies.

However narrowly, Thomas Clewes, George Banks and John Barnett avoided such a fate. The law had declared them innocent, and they were free to merge back into society, thus robbing the press of a dramatic conclusion and the public of an awful spectacle. Perhaps this goes some way to explaining why the Oddingley case was later overshadowed by others. Had Clewes, Banks and Barnett been executed, the sheer density of tangible objects recording their fate – the chapbooks, the pottery figures, the artistic recreations would have been far greater. All of these objects would have served as tactile little hooks, catching over and over again in people’s minds and dragging their memories and imaginations back to the case anew.

In Worcestershire, however, the story has always been remembered with strength and feeling. When Mary Pyndar, the youngest daughter of the Reverend, died in 1894 at the great age of 98, she left a bequest of ‘letters, papers, memoranda, notes of evidence, and copies of the local newspaper’ to the county records office, all of them concerning her father’s role in the original investigation. It was an extraordinary collection, and its receipt was announced in an article that reminded readers of the importance of the case. The piece began darkly, ‘Perhaps no event in the catalogue of crime

5

ever occasioned more horror and excitement in this part of the country than the double murder at Oddingley.’ Its author enthused, the ‘circumstances of this frightful occurrence have so often been narrated that it was by no means expected that anything hitherto untold with regard to it would turn up, especially after a lapse of nearly a century’. It was a matter of profound interest, then, that these papers had come to light, all of them ‘relating to the awful tragedy which has made the little village of Oddingley unenviably conspicuous ever since’.

And at intervals, like a periodic comet, the Oddingley story has returned to delight new audiences. In 1901 E. Perronet Thompson wrote a long essay for the

Gentleman’s Magazine

documenting the peculiarities and legal implications of the case. In 1960 David Scott Daniel published

Fifty Pounds for a Dead Parson

, a novel loosely based on the events, and in 1975 Angela Lanyon composed a play entitled

The Oddingley Affair

. The first faithful recreation of the murders would be published in America in 1991 by a American historian named Carlos Flick. His book

The Oddingley Murders

carried the tale across the Atlantic to a new readership, 185 years after Heming had supposedly made the journey himself.

It is Easter time in Oddingley now, and the verges are dotted with daffodils and dandelion. A gentle spring breeze blows from the Malvern Hills to the south-west. There is blackbird song, and lambs play in the pastures. Half a mile away Trench Wood looms on the escarpment above Netherwood Farm, where primroses, bluebells and pink campion are rising in the glades. In the sky a solitary buzzard circles over the young crops, its eyes fixed on the ground below.

Author’s Note

Damn His Blood

is a true story. This account is based entirely on contemporary and near-contemporary evidence of events in Oddingley and Worcester during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. All speech is drawn directly from source material – court reports, private letters, newspaper articles, printed chapbooks and pamphlets, and witness testimony.

Although written English was fast becoming standardised at this time, there are still variations in the spelling of several characters’ names. In particular Richard Heming was often recorded as ‘Hemming’ and George Banks often written as ‘Bankes’. I have chosen to drop one ‘m’ from Heming and the ‘e’ from Banks.