Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe

Read Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe Online

Authors: Simon Winder

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Austria & Hungary, #Social History

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

Place names

»

The Habsburg family

Tombs, trees and a swamp

»

Wandering peoples

»

The hawk’s fortress

»

‘Look behind you!’

»

Cultic sites

»

The elected Caesars

The heir of Hector

»

The great wizard

»

Gnomes on horseback

»

Juana’s children

»

Help from the Fuggers

»

The disaster

‘Mille regretz’

»

‘The strangest thing that ever happened’

»

The armour of heroes

»

Europe under siege

»

The pirates’ nest

»

A real bear-moat

The other Europe

»

Bezoars and nightclub hostesses

»

Hunting with cheetahs

»

The seven fortresses

A surprise visit from a flying hut

»

‘His divine name will be inscribed in the stars’

»

Death in Eger

»

Burial rites and fox-clubbing

»

The devil-doll

»

How to build the Tower of Babel

Genetic terrors

»

The struggle for mastery in Europe

»

A new frontier

»

Zeremonialprotokoll

»

Bad news if you are a cockatrice

»

Private pleasures

Jesus vs. Neptune

»

The first will

»

Devotional interiors

»

The second will

»

Zips and Piasts

The great crisis

»

Austria wears trousers

»

The Gloriette

»

The war on Christmas cribs

»

Illustrious corpses

»

Carving up the world

‘Sunrise’

»

An interlude of rational thoughtfulness

»

Defeat by Napoleon, part one

»

Defeat by Napoleon, part two

»

Things somehow get even worse

»

An intimate family wedding

»

Back to nature

A warning to legitimists

»

Problems with loyal subjects

»

Un vero quarantotto

»

Mountain people

The Temple to Glorious Disaster

»

New Habsburg empires

»

The stupid giant

»

Funtime of the nations

»

The deal

»

An expensive sip of water

Mapping out the future

»

The lure of the Orient

»

Refusals

»

Village of the damned

»

On the move

»

The Führer

The sheep and the melons

»

Elves, caryatids, lots of allegorical girls

»

Monuments to a vanished past

»

Young Poland

‘The fat churchy one’

»

Night music

»

Transylvanian rocketry

»

Psychopathologies of everyday life

»

The end begins

The curse of military contingency

»

Sarajevo

»

The Przemyśl catastrophe

»

Last train to Wilsonville

»

A pastry shell

»

The price of defeat

»

Triumphs of indifference

For Martha Francis

What is ‘known’ in civilized countries, what people may be assumed to ‘know’, is a great mystery.

Saul Bellow,

To Jerusalem and Back

The fat volunteer rolled onto the other straw mattress and went on: ‘It’s obvious that one day it will all collapse. It can’t last forever. Try to pump glory into a pig and it will burst in the end.’

Jaroslav Hašek,

The Good Soldier Švejk

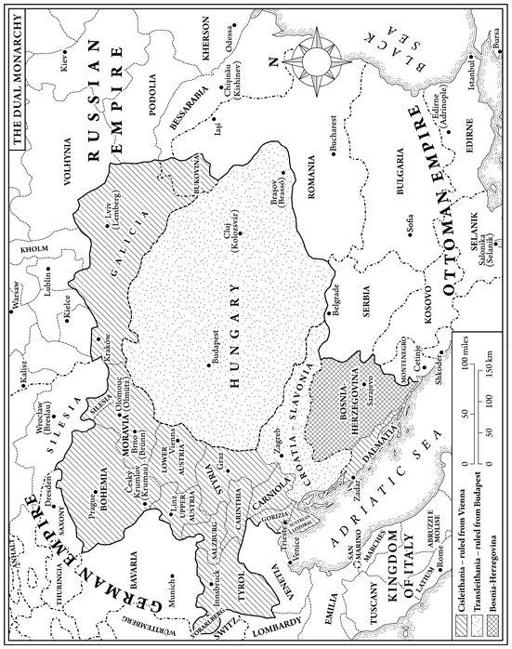

Emperor of Austria

Apostolic King of Hungary

King of Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Illyria

King of Jerusalem, etc.

Archduke of Austria

Grand Duke of Tuscany, Kraków

Duke of Lorraine, Salzburg, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, the Bukovina

Grand Prince of Transylvania

Margrave of Moravia

Duke of Upper & Lower Silesia, Modena, Parma, Piacenza, Guastalla, Auschwitz, Zator, Teschen, Friuli, Ragusa, Zara

Princely Count of Habsburg, Tyrol, Kyburg, Gorizia, Gradisca

Prince of Trent, Brixen

Margrave of Upper & Lower Lusatia, in Istria

Count of Hohenems, Feldkirch, Bregenz, Sonnenberg, etc.

Lord of Trieste, Kotor, the Wendish March

Grand Voivode of the Voivodship of Serbia, etc. etc.

Franz Joseph I’s titles after 1867, some of which are more in the nature of brave assertions than indicators of practical ownership

Maps

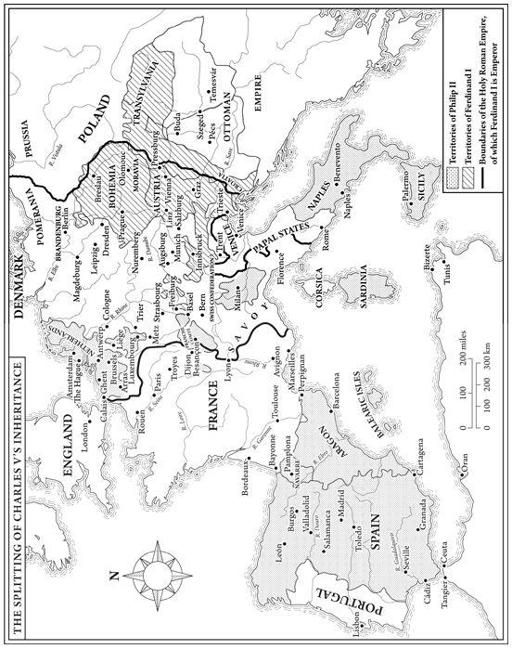

1. The splitting of Charles V’s inheritance

2. The Habsburg Empire, 1815

3. The Dual Monarchy

4. The United States of Austria

5. Modern Central Europe

Introduction

Danubia

is a history of the huge swathes of Europe which accumulated in the hands of the Habsburg family. The story runs from the end of the Middle Ages to the end of the First World War, when the Habsburgs’ empire fell to pieces and they fled.

Through cunning, dimness, luck and brilliance the Habsburgs had an extraordinarily long run. All empires are in some measure accidental, but theirs was particularly so, as sexual failure, madness or death in battle tipped a great pile of kingdoms, dukedoms and assorted marches and counties into their laps. They found themselves ruling territories from the North Sea to the Adriatic, from the Carpathians to Peru. They had many bases scattered across Europe, but their heartland was always the Danube, the vast river that runs through modern Upper and Lower Austria, their principal capital at Vienna, then Bratislava, where they were crowned kings of Hungary, and on to Budapest, which became one of their other great capitals.

For more than four centuries there was hardly a twist in Europe’s history to which they did not contribute. For millions of modern Europeans the language they speak, the religion they practise, the appearance of their city and the boundaries of their country are disturbingly reliant on the squabbles, vagaries and afterthoughts of Habsburgs whose names are now barely remembered. They defended Central Europe against wave upon wave of Ottoman attacks. They intervened decisively against Protestantism. They came to stand – against their will – as champions of tolerance in a nineteenth-century Europe driven mad by ethnic nationalism. They developed marital or military relations with pretty much every part of Europe they did not already own. From most European states’ perspective, the family bewilderingly swapped costumes so many times that they could appear as everything from rock-like ally to something approaching the Antichrist. Indeed, the Habsburgs’ influence has been so multifarious and complex as to be almost beyond moral judgement, running through the entire gamut of human behaviours available.

In the first half of the sixteenth century the family seemed to come close – as the inheritances heaped up so crazily that designers of coats of arms could hardly keep up – to ruling the whole of Europe, suggesting a ‘Chinese’ future in which the continent would become a single unified state. As it was, the Emperor Charles V’s supremacy collapsed, under assault from innumerable factors, his lands’ accidental origins swamping him in contradictory needs and demands. In 1555, Charles was obliged much against his will to break up his enormous inheritance, with one half going to his son, Philip, based in his new capital of Madrid, and the other going to his brother, Ferdinand, based in Vienna. At this break-point I follow the story of Ferdinand’s descendants, although the Madrid relatives continue to intrude now and then until their hideous implosion in 1700.