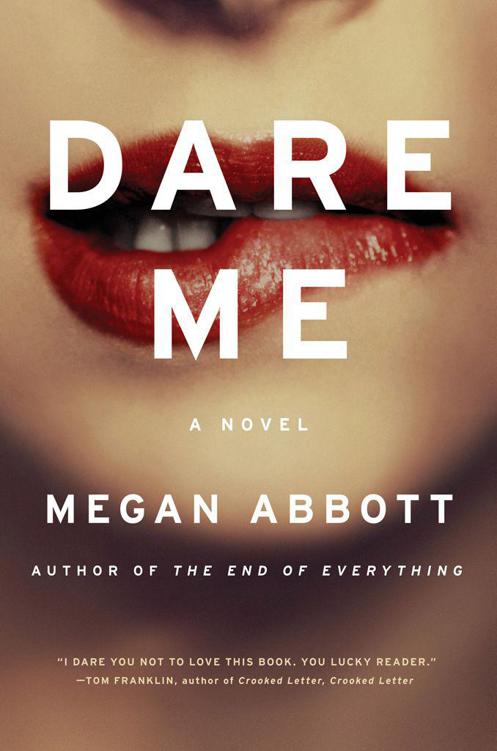

Dare Me

Authors: Megan Abbott

Tags: #Thrillers, #Coming of Age, #Suspense, #Azizex666, #Fiction

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For my parents, who taught me ambition

The curse of hell upon the sleek upstart

That got the Captain finally on his back

And took the red red vitals of his heart

And made the kites to whet their beaks clack clack.

—John Crowe Ransom

“Something happened, Addy.

I think you better come.”

The air is heavy, misted, fine. It’s coming on two a.m. and I’m high up on the ridge, thumb jammed against the silver button: 27-G.

“Hurry, please.”

The intercom zzzzzz-es and the door thunks, and I’m inside.

As I walk through the lobby, it’s still buzzing, the glass walls vibrating.

Like the tornado drill in elementary school, Beth and me wedged tight, jeaned legs pressed against each other. The sounds of our own breathing. Before we all stopped believing a tornado, or anything, could touch us, ever.

“I can’t look. When you get here, please don’t make me look.”

In the elevator, all the way up, my legs swaying beneath me, 1-2-3-4, the numbers glow, incandescent.

The apartment is dark, one floor lamp coning halogen up in the far corner.

“Take off your shoes,” she says, her voice small, her wishbone arms swinging side to side.

We’re standing in the vestibule, which seeps into a dining area, its lacquer table like a puddle of ink.

Just past it, I see the living room, braced by a leather sectional, its black clamps tightening, as if across my chest.

Her hair damp, her face white. Her head seems to go this way and that way, looking away from me, not wanting to give me her eyes.

I don’t think I want her eyes.

“Something happened, Addy. It’s a bad thing.”

“What’s over there?” I finally ask, gaze fixed on the sofa, the sense that it’s living, its black leather lifting like a beetle’s sheath.

“What is it?” I say, my voice lifting. “Is there something behind there?”

She won’t look, which is how I know.

First, my eyes falling to the floor, I see a glint of hair twining in the weave of the rug.

Then, stepping forward, I see more.

“Addy,” she whispers. “

Addy

…is it like I thought?”

FOUR MONTHS AGO

After a game,

it takes a half hour under the showerhead to get all the hairspray out. To peel off all the sequins. To dig out that last bobby pin nestled deep in your hair.

Sometimes you stand under the hot gush for so long, looking at your body, counting every bruise. Touching every tender place. Watching the swirl at your feet, the glitter spinning. Like a mermaid shedding her scales.

You’re really just trying to get your heart to slow down.

You think,

This is my body, and I can make it do things. I can make it spin, flip, fly.

After, you stand in front of the steaming mirror, the fuchsia streaks gone, the lashes unsparkled. And it’s just you there, and you look like no one you’ve ever seen before.

You don’t look like anybody at all.

At first, cheer was something to fill my days, all our days.

Ages fourteen to eighteen, a girl needs something to kill all that time, that endless itchy waiting, every hour, every day for something—anything—to begin.

“There’s something dangerous about the boredom of teenage girls.”

Coach said that once, one fall afternoon long ago, sharp leaves whorling at our feet.

But she said it not like someone’s mom or a teacher or the principal or worst of all like a guidance counselor. She said it like she

knew,

and understood.

All those misty images of cheerleaders frolicking in locker rooms, pom-poms sprawling over bare bud breasts. All those endless fantasies and dirty boy-dreams, they’re all true, in a way.

Mostly it’s noisy and sweaty, it’s the roughness of bruised and dented girl bodies, feet sore from floor pounding, elbows skinned red.

But it is also a beautiful, beautiful thing, all of us in that close, wet space, safer than in all the world.

The more I did it, the more it owned me. It made things matter. It put a spine into my spineless life and that spine spread, into backbone, ribs, collarbone, neck held high.

It was something. Don’t say it wasn’t.

And Coach gave it all to us. We never had it before her. So can you blame me for wanting to keep it? To fight for it, to the end?

She was the one who showed me all the dark wonders of life, the real life, the life I’d only seen flickering from the corner of my eye. Did I ever feel anything at all until she showed me what feeling meant? Pushing at the corners of her cramped world with curled fists, she showed me what it meant to live.

There I am, Addy Hanlon, sixteen years old, hair like a long taffy pull and skin tight as a rubber band. I am on the gym floor, my girl Beth beside me, our cherried smiles and spray-tanned legs, ponytails bobbing in sync.

Look at how my eyes shutter open and closed, like everything is just too much to take in.

I was never one of those mask-faced teenagers, gum lodged in mouth corner, eyes rolling and long sighs. I was never that girl at all. But I knew those girls. And when she came, I watched all their masks peel away.

We’re all the same under our skin, aren’t we? We’re all wanting things we don’t understand. Things we can’t even name. The yearning so deep, like pinions over our hearts.

So look at me here, in the locker room before the game.

I’m brushing the corner dust, the carpet fluff from my blister-white tennis shoes. Home-bleached with rubber gloves, pinched nose, smelling dizzyingly of Clorox, and I love them. They make me feel powerful. They were the shoes I bought the day I made squad.

FOOTBALL SEASON

Her first day.

We all look her over with great care, our heads tilted. Some of us, maybe me, even fold our arms across our chests.

The New Coach.

There are so many things to take in, to consider and set on scales, tilted always toward scorn. Her height, barely five-four, pigeon-toed like a dancer, body drum-tight, a golden collarbone popping, forehead high.

The sharp edges of her sleek bob, if you look close enough, you can see the scissor slashes (did she have it cut this morning, before school? she must’ve been so eager), the way she holds her chin so high, treats it like a pointer, turning this way and that, watching us. And most of all her striking prettiness, clear and singing, like a bell. It hits us hard. But we will not be shaken by it.

All of us, slouching, lolling, pockets and hands chirping and zapping—

how old u think? looka the whistle, WTF

—the texts flying back and forth from each hiccupping phone. Not giving her anything but eyes glazed, or heads slung down, attending to important phone matters.

How hard it must be for her.

But standing there, back straight like a drill officer, she’s wielding the roughest gaze of all.

Eyes scanning the staggered line, she’s judging us. She’s judging each and every one. I feel her eyes shred me—my bow legs, or the flyaway hairs sticking to my neck, or the bad fit of my bra, me twisting and itching and never as still as I want to be. As she is.

“Fish could’ve swallowed her whole,” Beth mutters. “You could’ve fit two of her in Fish.”

Fish was our nickname for Coach Templeton, the last coach. The one plunked deep in late middle age, with the thick, solid body of a semi-active porpoise, round and smooth, and the same gold post earrings and soft-collared polo shirt and sneakers thick-soled and graceless. Hands always snugged around that worn spiral notebook of drills penciled in fine script, serving her well since the days when cheerleaders just dandled pom-poms and kicked high, high, higher. Sis-boom-something.

Her hapless mouth slack around her whistle, Fish spent most of her hours at her desk, playing spider solitaire. We’d spot, through the shuttered office window, the flutter of cards overturning. I almost felt sorry for her.

Long surrendered, Fish was. To the mounting swagger of every new class of girls, each bolder, more coil-mouth insolent than the last.

We girls, we owned her. Especially Beth. Beth Cassidy, our captain.

I, her forever-lieutenant, since age nine, peewee cheer. Her right hand, her

fidus Achates.

That’s what she calls me, what I am. Everyone bows to Beth and, in so doing, to me.

And Beth does as she pleases.

There really wasn’t any need for a coach at all.

But now this. This.

Fish was suddenly reeled away to gladed Florida to care for her teenage granddaughter’s unexpected newborn, and here she is.

The new one.

The whistle dangles between her fingers, like a charm, an amulet, and she is going to have to be reckoned with.

There is no looking at her without knowing that.

“Hello,” she says, voice soft but firm. No need to raise it. Instead, everyone leans forward. “I’m Coach French.”

And you ma bitches,

the screen on my phone flashes, phone hidden in my palm. Beth.

“And I can see we have a lot to do,” she says, eyes radaring in on me, my phone like a siren, a bull’s-eye.

I can feel it still buzzing in my hand, but I don’t look at it.

There’s a plastic equipment crate in front of her. She lifts one graceful foot under the crate’s upper lip and flips it over, sending floor-hockey pucks humming across the shiny floor.

“In here,” she says, kicking the crate toward us.

We all look at it.

“I don’t think we’ll all fit,” Beth says.

Coach, face blank as the backboard above her, looks at Beth.

The moment is long, and Beth’s fingers squeak on her phone’s pearl flip.

Coach does not blink.

The phones, they drop, all of them. RiRi’s, Emily’s, Brinnie Cox’s, the rest. Beth’s last of all. Candy-colored, one by one into the crate. Click, clack, clatter, a chirping jangle of bells, birdcalls, disco pulses, silencing at last upon itself.

After, there’s a look on Beth’s face. Already I see how it will go for her.

“Colette French,” she smirks. “Sounds like a porn star, a classy one who won’t do anal.”

“I heard about her,” Emily says, still giddy-breathless from the last set of motion drills. All our legs are shaking. “She took the squad at Fall Wood all the way to state Semis.”

“Semis. Semi. Fucking. Epic,” Beth drones. “Be the dream.”

Emily’s shoulders sink.

None of us really cheer for glory, prizes, tourneys. None of us, maybe, know why we do it at all, except it is like a rampart against the routine and groaning afflictions of the school day. You wear that jacket, like so much armor, game days, the flipping skirts. Who could touch you? Nobody could.

My question is this:

The New Coach.

Did she look at us that first week and see past the glossed hair and shiny legs, our glittered brow bones and girl bravado? See past all that to everything beneath, all our miseries, the way we all hated ourselves but much more everyone else? Could she see past all of that to something else, something quivering and real, something poised to be transformed, turned out, made? See that she could make us, stick her hands in our glitter-gritted insides and build us into magnificent teen gladiators?