Dating Your Mom (7 page)

Authors: Ian Frazier

As a child of the sixties, I never tire of attending reunions of my friends and comrades who struggled together through that exciting era. My affinity group at the march on the Pentagon, at the Chicago Convention, and at the Boston Common still gets together once a month to reminisce. The guys in my men's rap group, veterans of so many coffee-and-cigarette late-night sessions in those distant Summers of Love, meet four times a year at a restaurant in Chinatown. And as for the “heads” who went looking for America on the Merry Pranksters' busâKesey, myself, Mountain Girl, Hassler, Zonker, Speed Limit, and the restâwe convene the first Tuesday of every month, no matter the weather, at twelve noon in the lobby of the Airway Motor Inn, beside LaGuardia Airport. At all these

reunions, we sixties survivors talk, compare notes, and wonder at the odd arcs our lives have described since the days when we awoke every morning expecting to find a world transformed by love, radiant and utopian, waiting on our doorstep.

reunions, we sixties survivors talk, compare notes, and wonder at the odd arcs our lives have described since the days when we awoke every morning expecting to find a world transformed by love, radiant and utopian, waiting on our doorstep.

For the most part, we find that the years have softened us. Now we can see the gray areas, whereas, before, all we could see was black and white. We are not so much saddened by these changes as we are gently bemused. No, things didn't turn out the way we thought they would. But then neither did we. We grew, nudged by forces both inside and outside ourselves, forces that we did not take into account at the time. Personal fulfillment in such areas as love, sexuality, careers, and coping gradually overrode the slogans of the sixties. The next thing we knew, we weren't the kids anymoreâwe were the adults, with kids of our own.

These days, when we get together to marvel at the major and minor miracles that brought us from there to here, we find that our conversation always seems to return to the children. Rather than bemoaning the shattered dreams of our revolutionary youth, more and more we find ourselves amazed at the unanticipated miracle of this new generation. Sixty million Americans born since the Beatles released “Rubber Soul”! Sixty million for whom the Berkeley Free Speech Movement is a historical event as remote as the Korean War! These kids are so different from us, and yet they're so wonderful, too. They're committed, competent, hardworking, goal-orientedâall the things we weren't. So levelheaded, so matter-of-fact, so accepting of the way the world is, so undismayed.

Not for them the wild caroming from rock music to drugs to gurus to radical politics which characterized the generation of the sixties; today's kids know what they want, and they know how they're going to get it. With all they have seen, they have a wisdom that many of their parents are still seeking.

Not for them the wild caroming from rock music to drugs to gurus to radical politics which characterized the generation of the sixties; today's kids know what they want, and they know how they're going to get it. With all they have seen, they have a wisdom that many of their parents are still seeking.

I know my friends sometimes may think I'm a bit of a pain when we're trading snapshots, the way I go on about my nephews Zachariah and Noah. They're my sister's kids from her first and second marriages, and I can't help bragging about them. Those kids really keep me sane. Surprisingly, I find very often it is I who learn from

them.

They have a terrific ability to deflate their elders' pretensions and follies with a sense of humor that is refreshingly down to earth. For example, when we ride the subway I always retreat into my shell, stare at my feet, and put on a blank expression, like so many other numbed adults. Not my nephews. They'll stroll up and down the car, looking into the shopping bag of one passenger, mussing the hair of another. They'll remove the glasses from this one and then replace them upside down, or they'll pull up the shirt collar of that one and read the label. If they see an attractive woman, why, they'll give her a pinch or a pat. They're so in touch with their feelingsâtheir anger, particularly. If someone laughs at them, they'll give him a lick over the head with a golf club that they carry just for that purpose, and then take his box radio. How they come up with these things I can't imagine. They have such marvelous savvy. They know where to sell gold chains, what arcades in Times Square are best for meeting older men from New Jersey, what day of the month the Social Security checks

arrive. Being around them is a twenty-four-hour-a-day experience in wonder. I can never tell what they're going to do next. I've long ago stopped trying to figure them out. All I do is love them, watch them, listen to them, and try to let them teach me.

them.

They have a terrific ability to deflate their elders' pretensions and follies with a sense of humor that is refreshingly down to earth. For example, when we ride the subway I always retreat into my shell, stare at my feet, and put on a blank expression, like so many other numbed adults. Not my nephews. They'll stroll up and down the car, looking into the shopping bag of one passenger, mussing the hair of another. They'll remove the glasses from this one and then replace them upside down, or they'll pull up the shirt collar of that one and read the label. If they see an attractive woman, why, they'll give her a pinch or a pat. They're so in touch with their feelingsâtheir anger, particularly. If someone laughs at them, they'll give him a lick over the head with a golf club that they carry just for that purpose, and then take his box radio. How they come up with these things I can't imagine. They have such marvelous savvy. They know where to sell gold chains, what arcades in Times Square are best for meeting older men from New Jersey, what day of the month the Social Security checks

arrive. Being around them is a twenty-four-hour-a-day experience in wonder. I can never tell what they're going to do next. I've long ago stopped trying to figure them out. All I do is love them, watch them, listen to them, and try to let them teach me.

And what about us grownupsâlapsed flower children, ex-peaceniks? Do we have anything to teach the kids of today? Can we tell them how it felt to live for an idea, to stand with arms linked against oppression and racism, to sing with our brothers and sisters about the world we were going to build? Sadly, we cannotâany more than our parents could tell us about their youth. And that is the irony: that the children of the eighties should help us to understand not only our own time but also our parents' (the children of the eighties' grandparents') time; because we, the parents of today, understand better why our parents acted toward us as they did when we look at our own children and see that in twenty years, when they have children of their own, they will understand us better âthe way we now understand our parents better. And maybe then the kids of today will begin to understand the spirit of the sixties.

Composer, conductor, critic, teacher, iconoclast, and grand old man, Igor Stravinsky bestrode this century like a colossus, with feet on two different continents. Already respected and popular in Europe for writing pieces like

Le Sacre du Printemps,

he became equally if not more famous in his adopted country of America. The many friends he made here remember him as a man of breathtaking talent, whether he was composing an epochal symphony or playing shadow puppets in the candlelight after a small dinner party. Like many other geniuses, he was generous, almost profligate, with his gifts. He would write beautiful phrases of music on restaurant napkins and give them to friends, acquaintances, even passersby. Thoughts bubbled forth from him in such a torrent that often when he

was sitting in his den writing a letter to a friend he would impulsively grab for the telephone, look up his friend's number in his address book while holding the phone to his ear with his shoulder, and dial. In a matter of seconds, he would be pouring out ideas that might have required days, even weeks, to travel through the mails. At the other end of the line, the friend would listen with delight as the great man went on, humming or singing at times, until finally he was “all talked out.” Then Stravinsky would bid his grateful hearer goodbye, and, in the pleasant afterglow of inspiration, he would crumple up the unfinished letter, throw it in the wastebasket, and mix himself a cocktail.

Le Sacre du Printemps,

he became equally if not more famous in his adopted country of America. The many friends he made here remember him as a man of breathtaking talent, whether he was composing an epochal symphony or playing shadow puppets in the candlelight after a small dinner party. Like many other geniuses, he was generous, almost profligate, with his gifts. He would write beautiful phrases of music on restaurant napkins and give them to friends, acquaintances, even passersby. Thoughts bubbled forth from him in such a torrent that often when he

was sitting in his den writing a letter to a friend he would impulsively grab for the telephone, look up his friend's number in his address book while holding the phone to his ear with his shoulder, and dial. In a matter of seconds, he would be pouring out ideas that might have required days, even weeks, to travel through the mails. At the other end of the line, the friend would listen with delight as the great man went on, humming or singing at times, until finally he was “all talked out.” Then Stravinsky would bid his grateful hearer goodbye, and, in the pleasant afterglow of inspiration, he would crumple up the unfinished letter, throw it in the wastebasket, and mix himself a cocktail.

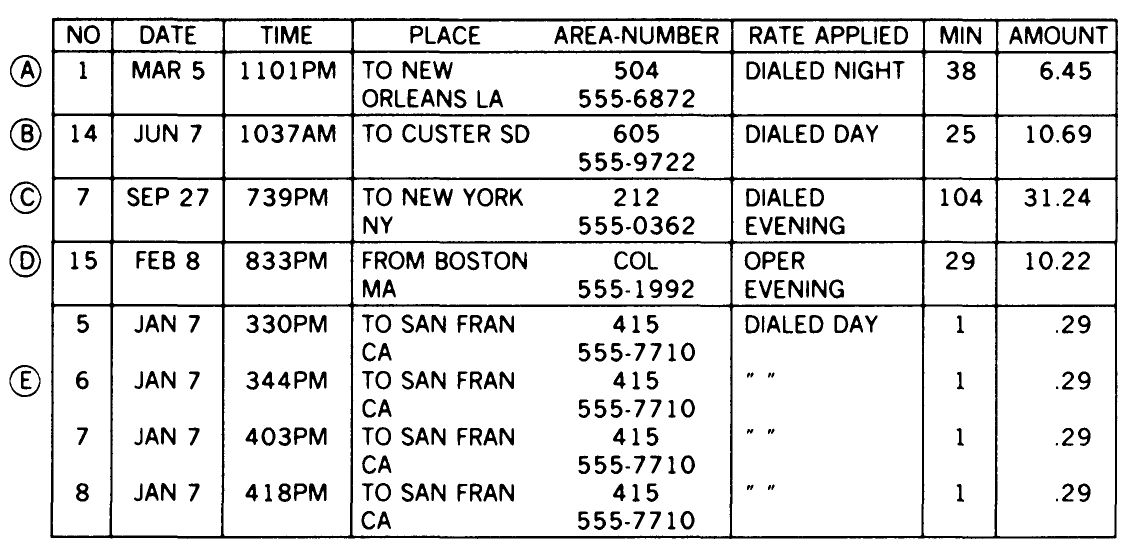

Fortunately for us, his heirs, Stravinsky was a man aware of his place in history. With careful consideration for the students and biographers he knew would follow, he saved his telephone bills from year to year, and before his death he donated the entire corpus to the K-Tel Museum of the Best Composers Ever. What a fascinating picture these phone bills paint! With their itemized lists of long-distance calls and charges, they are like paper airplanes thrown to us from the past, providing a detailed record of the seasons of Stravinsky's mind in the multihued pageant of life as he lived it on a daily basis. And what better time for a close examination of the treasures his phone bills contain than this, the year after the centennial of Stravinsky's birth? (Actually, the centennial year itself would probably have been better, but even though this year might not be as good a time as last year, still, it is almost as good.) Now let us turn to the documents:

This call, made not long after Stravinsky moved to America and had his phone hooked up, shows him adjusting quickly to the ways of his new country. With scenes of Old World poverty fresh in his memory, he has prudently waited to place the call until 11:01 p.m., the very moment when the lowest off-peak rates go into effect. Such patience and calculation indicate a call that was professional rather than social in nature. Almost certainly, the recipient was Stravinsky's fellow composer Arnold Schoenberg. It was common knowledge that Schoenberg often vacationed in New Orleans, where he enjoyed the food, the atmosphere, and the people. Stravinsky may have found out from a mutual friend where Schoenberg was staying and then surprised him with this call. Always one to speak his mind, Stravinsky probably began by telling Schoenberg that his dodecaphonic methods of musical composition were a lot of hooey. Very likely, Schoenberg would have bristled at this, and may well have reminded Stravinsky that great art, like the Master's own Sacre, need not be immediately accessible. Stravinsky then probably made a smart remark comparing Schoenberg's methods to the methods of a troop of monkeys with a xylophone and some hammers. This probably made Schoenberg pretty mad, and it is a testament to the great (albeit hidden) regard each man had for the other that the call lasted as long as it did. Possibly, Schoenberg just held his temper and said something flip to defuse the situation, and then Stravinsky moved on to another subject. Inasmuch as they never spoke again, this intense thirty-eight-minute phone conversation may represent a seminal point in the history of twentieth-century music theory.

This call, made not long after Stravinsky moved to America and had his phone hooked up, shows him adjusting quickly to the ways of his new country. With scenes of Old World poverty fresh in his memory, he has prudently waited to place the call until 11:01 p.m., the very moment when the lowest off-peak rates go into effect. Such patience and calculation indicate a call that was professional rather than social in nature. Almost certainly, the recipient was Stravinsky's fellow composer Arnold Schoenberg. It was common knowledge that Schoenberg often vacationed in New Orleans, where he enjoyed the food, the atmosphere, and the people. Stravinsky may have found out from a mutual friend where Schoenberg was staying and then surprised him with this call. Always one to speak his mind, Stravinsky probably began by telling Schoenberg that his dodecaphonic methods of musical composition were a lot of hooey. Very likely, Schoenberg would have bristled at this, and may well have reminded Stravinsky that great art, like the Master's own Sacre, need not be immediately accessible. Stravinsky then probably made a smart remark comparing Schoenberg's methods to the methods of a troop of monkeys with a xylophone and some hammers. This probably made Schoenberg pretty mad, and it is a testament to the great (albeit hidden) regard each man had for the other that the call lasted as long as it did. Possibly, Schoenberg just held his temper and said something flip to defuse the situation, and then Stravinsky moved on to another subject. Inasmuch as they never spoke again, this intense thirty-eight-minute phone conversation may represent a seminal point in the history of twentieth-century music theory. This call is of particular interest to the student because of its oddity. One is compelled to ask, “Who did Stravinsky know in Custer, South Dakota?” He never went there; none of his friends or relatives ever went there; the town has no symphony orchestra. So why did he call there? It is hard to believe that on a June morning the sudden urge for a twenty-five-minute chat with a person in Custer, South Dakota, dropped onto Stravinsky out of the blue. No, we must look elsewhere for an explanation. Two possibilities suggest themselves: (1) an acquaintance of the composer, perhaps an occasional racquetball partner, a fan, even a delivery boy from the supermarket, comes by the Stravinskys', sees no one is in, and takes the opportunity to make a long-distance call and stick someone else with the tab; or (2) the telephone company made an error. In either event, Stravinsky should not have paid the ten dollars and sixty-nine cents, and I believe it was taken from him unfairly, just as much as if a mugger had stolen it from him on the street.

This call is of particular interest to the student because of its oddity. One is compelled to ask, “Who did Stravinsky know in Custer, South Dakota?” He never went there; none of his friends or relatives ever went there; the town has no symphony orchestra. So why did he call there? It is hard to believe that on a June morning the sudden urge for a twenty-five-minute chat with a person in Custer, South Dakota, dropped onto Stravinsky out of the blue. No, we must look elsewhere for an explanation. Two possibilities suggest themselves: (1) an acquaintance of the composer, perhaps an occasional racquetball partner, a fan, even a delivery boy from the supermarket, comes by the Stravinskys', sees no one is in, and takes the opportunity to make a long-distance call and stick someone else with the tab; or (2) the telephone company made an error. In either event, Stravinsky should not have paid the ten dollars and sixty-nine cents, and I believe it was taken from him unfairly, just as much as if a mugger had stolen it from him on the street. Here we have a side of the composer's personality which we must face unflinchingly if we are to be honest. Every man has a dark side; this is his. On an evening in late September, just after dinner, Stravinsky placed a call to New York and talked for a hundred and four minutes. A

Here we have a side of the composer's personality which we must face unflinchingly if we are to be honest. Every man has a dark side; this is his. On an evening in late September, just after dinner, Stravinsky placed a call to New York and talked for a hundred and four minutes. Ahundred and four minutes!

That's almost two hours! As one ear got tired and he switched the phone to the other, he obviously did not realize how inconsiderate he was being. It was as if he were the only person in the whole world who needed to use the phone. What if his wife wanted to make a call? What if somebody was trying to call him from a pay phone, dialing every five minutes, only to hear the

busy signal's maddening refrain? Surely, after an hour or so he could have found a polite way to hang up. Surely, he could have at least made an effort to think of someone other than himself. But he didn'tâhe just kept yakking along, without a worry or a care, for over one hundred selfish minutes.

We should always remember that the perfection we demand of our heroes they cannot, in reality, ever attain.

Calling Stravinsky collect would seem to be the act of either a madman or a geniusâor both. Yet here before us is the evidence that not only did someone pull such a stunt but Stravinsky actually went along with it and accepted the charges. In all likelihood, the caller was a young admirer, possibly a music student (Boston is known for its many music schools), who found himself in the middle of a creative crisis with nowhere else to turn. It shows how nice Stravinsky could be when he wanted to be that he gave the young man a shoulder to cry on, as well as some helpful encouragement. The disconsolate youth probably said that he despaired of ever finding an entry-level position as a composer, and that even if he did he was sure he would never make very much per week. Stravinsky may have gently reminded the lad that music is not a job but a vocationâwhich its true disciples cannot denyâand he may have added that a really good composer can earn a weekly salary of from eight hundred to one thousand dollars. Comforted, the student probably hung up and returned to his work with renewed dedication, and later went on to become Philip Glass or Hugo Winterhalter or André Previn. As success followed success, the young student (now

Calling Stravinsky collect would seem to be the act of either a madman or a geniusâor both. Yet here before us is the evidence that not only did someone pull such a stunt but Stravinsky actually went along with it and accepted the charges. In all likelihood, the caller was a young admirer, possibly a music student (Boston is known for its many music schools), who found himself in the middle of a creative crisis with nowhere else to turn. It shows how nice Stravinsky could be when he wanted to be that he gave the young man a shoulder to cry on, as well as some helpful encouragement. The disconsolate youth probably said that he despaired of ever finding an entry-level position as a composer, and that even if he did he was sure he would never make very much per week. Stravinsky may have gently reminded the lad that music is not a job but a vocationâwhich its true disciples cannot denyâand he may have added that a really good composer can earn a weekly salary of from eight hundred to one thousand dollars. Comforted, the student probably hung up and returned to his work with renewed dedication, and later went on to become Philip Glass or Hugo Winterhalter or André Previn. As success followed success, the young student (nowadult) would always remember the time a great man cared enough to listen.

This delightful series of calls reveals the Master at his most puckish. The time is a drab afternoon in midwinter; Stravinsky is knocking around the house at loose ends, possibly with a case of the post-holiday blahs. Maybe he starts idly leafing through a San Francisco telephone directory. Then, perhaps, a sudden grin crosses his face. He picks a number at random and dials. One ring. Two rings. A woman's voice answers. Stravinsky assumes a high, squeaky voice. “Is Igor there?” he asks. Informed that he has the wrong number, he hangs up.

This delightful series of calls reveals the Master at his most puckish. The time is a drab afternoon in midwinter; Stravinsky is knocking around the house at loose ends, possibly with a case of the post-holiday blahs. Maybe he starts idly leafing through a San Francisco telephone directory. Then, perhaps, a sudden grin crosses his face. He picks a number at random and dials. One ring. Two rings. A woman's voice answers. Stravinsky assumes a high, squeaky voice. “Is Igor there?” he asks. Informed that he has the wrong number, he hangs up.Fourteen minutes pass. Then he calls back. In a low voice this time, he repeats his question: “Hi. Is Igor there?” Sounding a bit surprised, the woman again replies in the negative.

Other books

Mathew's Tale by Quintin Jardine

Choke by Stuart Woods

How to Be a Submissive Wife by Pearl, Jane

Chasing Fire 1: The Innocent (BDSM Erotic Romance) by Mara Stone

Souls of Aredyrah 2 - The Search for the Unnamed One by Akers, Tracy A.

Linger Awhile by Russell Hoban

The Reluctant Warrior by Pete B Jenkins

Too Close to the Edge by Susan Dunlap

The Wake (And What Jeremiah Did Next) by Colm Herron

Traffic by Tom Vanderbilt