Daughter of Time: A Time Travel Romance (2 page)

Read Daughter of Time: A Time Travel Romance Online

Authors: Sarah Woodbury

“

Dw i'n dy garu di.”

“I love you too.” I held out a hand to Anna.

She turned over on her stomach, letting her legs dangle over the

edge of the cushion, slid down from the couch, and ran to me. I

bundled her into her coat, put her on my hip, and reached for my

purse again. “We’ll be back.”

“Bye,” Elisa and

Mom

said in unison.

Anna waved as she always did, her little

fist opening and closing. “Bye.”

Once in my little blue Honda, with Anna

buckled into her car seat in the middle of the back seat, I allowed

myself a deep breath. I leaned my head against the seat rest.

We’ll be okay.

I buckled myself in, started the car, and

headed away from my mother’s house.

It was only four miles to the ice cream

parlor. I took the turns carefully, reliving again, as I did in my

dreams, what must have happened to Trev that night. Halfway there,

I realized we were approaching the spot where he died. I’d been

avoiding it the whole week. How could I have forgotten to take a

different route this time? The intersection lay ahead of us. My

stomach clenched.

I come home from my job at the library on

campus. I’d been able to put Anna in bed before I left, but as I

push open the kitchen door at midnight, I can see through the space

between the kitchen counter and the cupboards into the living room,

which is dark except for the flickering light from the television.

There she is, lying on the couch with her eyes open, watching

something that looks like Jaws 17. I set my books on the kitchen

counter and Trev twists in his armchair. He has a beer in one hand

and a lit cigarette in the other.

I just stand there, staring at him, anger,

recriminations, and hatred boiling up inside me. There’s a moment

when I try to stop them, knowing it’s pointless to complain, trying

to make allowances for the crappy upbringing he had that led him to

this moment. But then they spill out. “Trev,” I say, trying to keep

my voice down and reasonable-sounding. “I’ve asked you not to smoke

in the house. It’s bad for Anna.”

“

It’s fucking cold out there!” he said,

hitching himself higher in the chair. He’s lost so much weight, his

body doesn’t have the mass to stay fixed in the seat anymore and

keeps sliding down it. “I’ll fucking die if I go out

there.”

“

Trev,” I say again. “You’re

smoking.”

“

And I’m fucking dying anyway. Shit,” he

says, getting angry between one instant and the next. He reaches

beside him and throws the pillow in his chair across the room like

a frisbee. It hits the television, which fizzles out. We’ve never

been able to afford a better TV and in that moment, I’m glad. But

Trev is mad.

He pushes out of his chair and approaches

me, taking small mincing steps. He changes his voice to something

whiny and high, a supposed imitation of my own. “Trev,” he says.

“Trev don’t smoke. Trev, you’re keeping Anna awake. She needs her

sleep. Trev, you shouldn’t be drinking while you’re on your

meds.”

I back away, glancing at Anna to see how

she’s taking this. Her eyes are closed. I hope that she really is

asleep, now that the glare from the television is gone, but I don’t

see how she could be.

“

Trev,” I say, one more time.

“Don’t.”

“

Don’t fucking say my name!” He backhands

me across the face before I can get out of the way. I fall against

the kitchen table and onto the floor, and then crab-walk backward,

hurrying before he can hit me again. He stumbles forward and leans

down, getting right in my face, his hand fisted. “I’ll do what I

please in my own house!”

Then he straightens. He’s breathing hard;

this has taken more out of him than it used to. He staggers as he

makes his way to the kitchen door and opens it. I don’t say

anything and neither does he as he walks away from me, into the

night.

When the police officer came to the house,

he told me that Trev hadn’t braked at a stop sign where the road

teed. Instead of turning right or left as required, he’d driven

straight ahead into a tree. Facing that same junction, I eased up

on the gas. My eyes blurred as we approached it and I fought back

the tears, wiping at my cheeks with the back of one hand while the

other clenched the steering wheel. I pressed the brake hard, as I

knew he had not—but then . . .

I’m not stopping!

“Anna!” Her name came out a shriek as the

car skidded sideways on the black ice I’d not known was there. I

swung the wheel, struggling to correct our course. I managed to

alter it enough to avoid the tree on which Trev had lost his life,

but slid instead toward the twenty-foot high roadcut to its left

which was fronted by a shallow ditch. Time hung suspended during

that half second before impact, stretching before me. My hands

whitened on the wheel, my throat tightened from unshed tears, and

Anna cried in the back seat, frightened by the panic in my

voice.

Then everything speeded up as the car slid

into the cut

and then through it.

An abyss opened before me—a yawning

blackness that gave me the same hollow rushing in my ears I’d felt

in the morgue. A lifetime later, we were through it or across

it—whatever

it

was. I registered gray-blue sky and sea

before the car bounded headfirst down an incline and skidded into a

marsh. It came to an abrupt halt as the world flipped forward.

Instinctively, I threw up my hands to protect my head but the

steering wheel rushed at my face. I tasted plastic and blood—pain,

and then nothing.

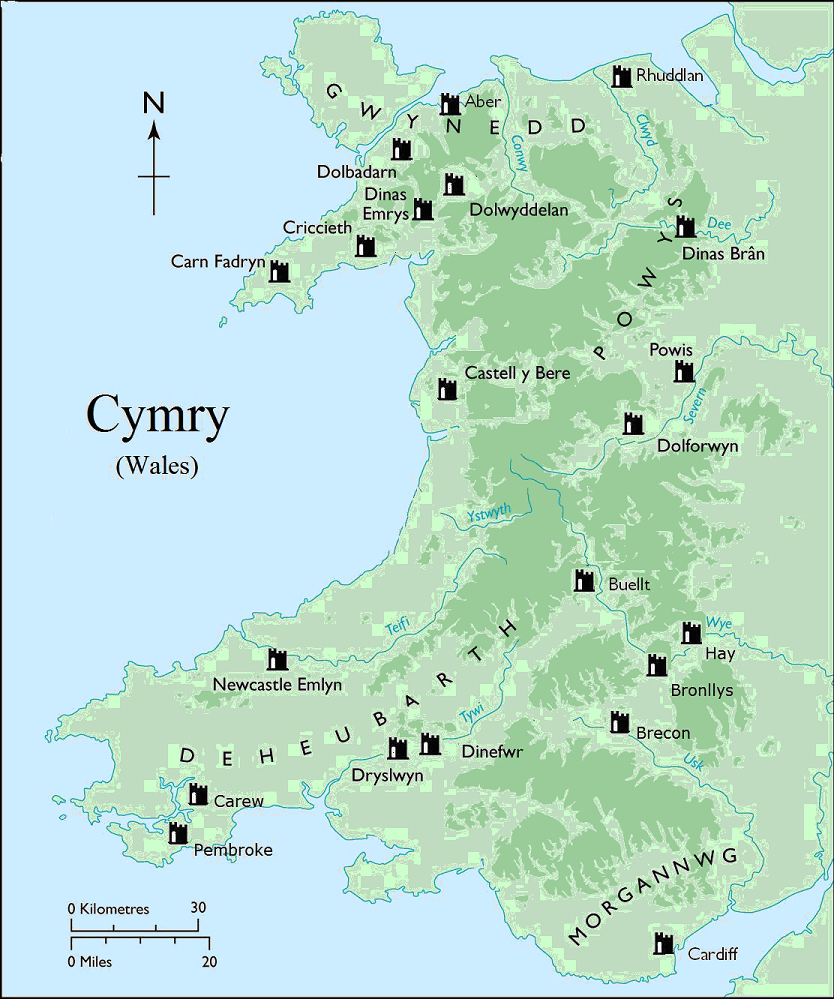

Llywelyn

I

n the year of

our Lord, twelve hundred, and sixty-eight.

May God go with

you.

The priest’s parting invocation for the close of evening

mass echoed in my head as I took the steps two at a time up to the

battlements of Castell Criccieth. Darkness was coming on and I was

looking forward to seeing the sun set over the water to the

southwest. They say that we, the Welsh, are always caught between

the mountains and the sea. On a day like today, with the wind

whipping the sea into a froth and the snow-covered peak of Yr

Wyddfa—Mt. Snowdon—towering above the castle, both tugged at

me.

I breathed in the salty air, feeling its

humid scent. In truth, I loved it all. It was as if my boots had

been planted in the soil of Wales and no power in heaven or earth

could move me from this spot.

My small corner of Europe had been

threatened, encircled, and enslaved by kings of many nationalities

since Caesar first crossed the channel into England over a thousand

years before. Throughout it all, we Welsh had, in turn, fought and

run, thrown ourselves upon our enemies, and hidden in our

mountains. Each foreign king had eventually discovered that our

resistance to his rule was as inevitable as the rain, and our place

in Wales as permanent as the rock on which we stood.

And now King Henry of England knew it too.

The triumph of my ascendancy was like a fire in my belly that would

not go out. Every month that passed allowed me to more strongly

grasp each hamlet, each pasture and village in Wales as my own.

As I stood on the battlements, the wind in

my hair, the words my bard had pronounced at the New Year’s feast

rang again in my ears, each stanza crashing over me like the waves

that hit the shore below:

There stands a lion, courageous and

brave . . . Llywelyn, ruler of Wales.

Was I too proud, too full

of hubris, that I heard these words, long past the ending of the

feast?

The sun was reddening as it lowered in the

sky and I turned my back on it to look up at Yr Wyddfa, its snowy

peaks now pink from the reflected light. It had been a sunny day,

unusual for January, and this was a rare treat. I was just turning

to look northeast again, when a—

what is that thing!

—surged

out of the trees that lined the edge of the marsh abutting the

seashore to the west of the castle, beacons shining from the front

of it, and buried itself headfirst in the marsh.

Stunned, I couldn’t move at first, but the

unmistakable wail of a small child, faint at this distance, rose

into the air. Afraid now that the—

thing? chariot?—

would sink

into the marsh before I could reach it, I ran across the

battlements to the stairs, down them, out a side door of the keep,

and into the bailey. I spied Goronwy ap Heilin, my longtime

counselor and friend, just coming into the castle from under the

gatehouse and I strode toward him.

“My lord!” He checked his horse, concern

etched in every line of his squat body. He was dressed in full

armor, his torso made more bulky by its weight. His helmet hid his

prematurely gray hair.

I hesitated for a heartbeat and then threw

myself onto the horse behind him. Goronwy gathered his reins and

chose not to argue, even though he had to know that his horse

couldn’t carry the two of us for long.

“We must hurry,” I said.

Goronwy spurred his horse back the way he’d

come, out the gate and down the causeway that led from the castle

to the village. We trotted through the village and turned left,

trying to reach the point where the vehicle had gone in.

While Castell Criccieth itself was built on

a high rock that could be reached by a narrow passage, the marsh

associated with it was legendary. The pathway fell off dangerously

into a sucking swamp, fed by an unnamed underground stream that

seeped its way to the sea. I’d not lost anyone in it recently and

didn’t want to lose anyone now, but as we came to a sudden halt

along the road as it turned, I wasn’t sure what to do.

The wail of the child was more evident the

closer we got, though it was no longer constant but punctuated

every now and then by silence. Perhaps he was tiring, too exhausted

to maintain his cries. I could imagine him gasping for air between

breaths as a child does, especially when he is unsure if anyone is

coming to help.

“By all that is holy!” Goronwy said, seeing

the vehicle for the first time. “What is it?”

“I don’t know. A chariot of some kind,

carrying two from the looks.” It had four wheels, as wagons do, two

of which spun slowly, high in the air. The vehicle had moved so

fast and without any visible means of propulsion that I couldn’t

imagine what had thrown it out of the forest and into my marsh in

the first place. It was coated in a sturdy material that wasn’t

wood, and was, unaccountably, blue in color.

Goronwy took in the situation in a glance

and gestured to the point where the chariot had driven into the

marsh. “By the trees, my lord,” he said. “It looks as if the ground

is more solid there.”

“Yes. Keep going.”

We continued on the road until it reached

the trees and then along their edge until we stopped only a few

yards from the chariot. The sun was nearly down now and I cursed

myself for forgetting a torch. We dismounted and I took a step

toward the chariot, but my foot immediately stuck a few inches into

the mud. To put my weight down further would ensure the loss of my

boot.

“Careful, my lord,” Goronwy said.

I stepped back. “We’ll find another

way.”

Goronwy spied several fallen logs in the

woods that edged the marsh and we lugged them towards the marsh to

act as a bridge between us and the chariot. Urgency filled both of

us so with me in the lead, we stepped carefully across them to the

chariot. I touched one of the side walls of the vehicle, hesitant,

noting that it curved away from me, smooth as the water in my

washing basin.

“Now what?” Goronwy said. “Do you need my

help to get them out?”

Goronwy was concerned because the narrow

bridge we’d built was sinking into the marsh under our combined

weight. For us to stand together on one end might doom the both of

us. I peered through the clear glass that separated me from the

baby in the rear of the vehicle and from the woman in the front

seat. The light of the setting sun reflected off the glass and I

could see fingerprints smudging the window. The sight struck me as

so

commonplace

that it gave me confidence.

“No. Stay where you are.”

I surveyed the expanse of incredibly worked

metal of which the vehicle was composed. As I studied it, I

realized it was not all one piece as I’d first thought. It had been

put together in sections, and then the pieces of metal attached

together. Still, except for two black elongated objects aligned

with each other half way down the sides, there was nothing to hold

onto. I grasped one of them, hoping it was what it looked like: a

latch.

I pulled on it and miraculously, the door to

the chariot opened. I had to duck into the doorway since the

chariot had a roof that was two feet less than my height. The girl

slumped over a wheel affixed to the wall in front of her. I pulled

her back into her seat and frowned at the line of blood across her

forehead. Except for the one wound, I couldn’t see any other

injuries. Her eyes were closed, however, and she was unconscious.

It surprised me, in that half a second it took to look her over,

that she was an ordinary girl, admittedly dressed strangely and

half my age, but there was nothing about her that told me why she

would be driving this incredible chariot.