Daughters of the KGB (38 page)

Read Daughters of the KGB Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Modern, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Intelligence & Espionage

Working in France at the time of Pacepa’s defection was a 30-year-old agent of the Directia Informatii Externe (Foreign Intelligence Directorate of the Securitate). Born Matei Hirsch, but using the name of Matei Haiducu, he was the privileged son of a high official in Ceausescu’s Interior Ministry, whose task was to steal French technology, especially in the realm of nuclear research. However, in January 1981, Haiducu received an order from Bucharest to assassinate two Romanian émigré writers living in France named Virgil Tanase and Paul Goma. In a sense it was a repeat of the Markov murder, with a different method, because the two intended victims had irritated Ceausescu – in Tanase’s case by describing the dictator as ‘His Majesty Ceausescu the First’. Instead of doing that, Haiducu reported his orders to DST, the French counter-espionage service. With Gallic subtlety, they let him squirt poison from an adapted fountain pen into a drink that was to be swallowed by Goma, but he ‘accidentally’ spilled the poisoned chalice. They then assisted Haiducu to stage the kidnapping of Tanase in front of witnesses on 20 May 1982, after which he was spirited away to a quiet hotel in Britanny with Goma. With French President François Mitterrand in on the act, a press conference was called to protest at the flagrant outrage, and Mitterrand cancelled a scheduled visit to Romania to add verisimilitude. This enabled Haiducu to return as a hero to Bucharest and be rewarded with promotion and the rare privilege of a holiday abroad with his family, from which they did not return home.

6

By the 1980s Romania had the lowest standard of living and the most appalling food shortages of the satellite countries. In an attempt to pass the buck, the Securitate arrested 80,000 peasants as ‘saboteurs’ who had obstructed the infallible dictates of the government.

7

Photographs of the time show peasants in shabby clothes riding on horse-drawn carts along unmade roads in scenes where little had changed since the previous century. Nothing worked. No home was anyone’s castle: forcible entry was routine, as was the planting of hidden microphones.

The collapse of the regime was inevitable in 1989. It began on 14 December in Timisoara, a major city in the west of the country, where Securitate officers attempted to arrest a Hungarian pastor named László Tokes. Encouraged by the news from the other satellite states, his parishioners made a human chain around his house. Most unusually, local Romanians joined in the struggle until it seemed the whole population was engaged. After three days, Ceausescu ordered soldiers and police to shoot the demonstrators to ‘restore order’. The Securitate and some soldiers did so; other soldiers refused to obey the order. Tokes was arrested after 100-plus people had been killed and many wounded. Returning from a state visit to Iran on 21 December, Ceausescu ordered a massive rally in Bucharest to endorse his authority. Televised live, its great surprise was the booing from younger people in the crowd, swiftly followed by a roar of anger from most of the people. The screen faded to black as Securitate snatch squads dived into the crowd to arrest the ringleaders. Incredulous at meeting resistance, they began shooting wildly, reportedly killing several hundred people. Ceausescu ordered Minister of Defence General Vasile Milea to send troops against the people. Milea refused and committed suicide, or was murdered. The army then went openly over to the side of the protesters.

On 22 December an enormous crowd stormed the Central Committee building in Bucharest. The president and his wife escaped from the roof in a helicopter that landed about 60 miles to the north-west, near Târgoviste, where they were recognised and arrested by soldiers. Meanwhile Securitate riot police were launching three days of civil war against the people and army units, in which 1,140 people were killed and more than 3,000 wounded. Their main target was the state television building, where the National Salvation Council of dissidents, students and officials who had fallen foul of the dictator was announcing live to Romanians and the world what was happening.

On 25 December a show trial was filmed, with the president and his wife helped from an armoured car in which they had been held for three days, moving continuously from place to place to prevent a rescue by Securitate shock troops. The kangaroo court, held in a barracks at Târgoviste, heard no witnesses, just a succession of accusations. Ceausescu seemed too stunned to protest much, in contrast to his wife, who screamed at the guards when the impromptu court, after a 90-minute deliberation, ordered a squad of paras to execute the couple immediately. Caught on film, they were shot in a courtyard and shown lying in pools of their own blood. The film was repeatedly broadcast on television, and may be viewed on YouTube. In one Western television interview, several respectable-looking ladies in Bucharest said that they had watched it many times in the days following the execution. The site of the execution – bullet holes still visible in the wall – is now a tourist attraction.

Such was the speed of this bloody revolution that many people believed it must all have been agreed in advance with Moscow. The Securitate snipers stopped shooting people after a few days, but that the organisation was merely dormant – even continuing to occupy the same premises as before the revolution – became clear in June 1990 when the new government ordered Securitate units into the streets again to beat up students occupying Bucharest’s University Square. Scuffles turned into a riot, with cars set on fire and overturned, windows smashed and public buildings occupied. Figures of those killed and wounded vary widely. The government then sent trains to ferry Ceausescu’s rent-a-mob of miners to the capital, so they could teach the students a lesson. The miners ran wild for three days of terror, beating up intellectuals, students and people with foreign contacts.

As in the other former satellites, one difficult problem for the new government was what to do with the Securitate archive containing millions of files. The majority were placed in the care of the new internal security service Serviciul Rôman de Informatii (SRI) and some, presumably relating to foreign espionage of the Ceausescu years, given to Serviciul de Informatii Externe (SIE), the new foreign intelligence service. This proved not to be a good idea: many files were leaked for political reasons or in return for favours or protection, and so the archives were deposited in a specially created body, Conciliul National pentru Studearea Archivelor Securitâtii (CNSAS). Theoretically, this body works like the BStU in Berlin, granting access to personal files for Romanian citizens who can prove their identity and entitlement to see them. It is, however, widely believed that, like Orwell’s pigs, some politicians and officials have more rights to poke their snouts into the archive trough than has the general population.

Notes

1

. Dallas,

Poisoned Peace

, p. 360

2

. This shocked Western leaders, who were still expecting Stalin to abide by the terms of the Yalta conference

3

. Brogan,

Eastern Europe

, p. 220

4

. Sudoplatov,

Special Tasks

, p. 232

5

. Applebaum,

Iron Curtain

, p. 296

6

. Dobson and Payne,

Dictionary of Espionage

, pp. 347–8

7

. Brogan,

Eastern Europe

, p. 220

21

F

ROM

S

ERFDOM TO THE

S

IGURIMI

S

ECRET

P

OLICE

The break-up of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War has had long-term impact throughout the Balkans, where the mutual hatred of population groups defined by language or religion had been held in check by Constantinople’s hegemony. It unleashed a struggle which still continues a century later with minorities fighting to join their kindred in neighbouring countries, to dominate their ethnic or religious enemies and/or fight off attempts by other peoples to take them over. Nowhere were the consequences worse than in ancient Illyria – modern Albania, whose native name, Shqiperia, is translated as ‘land of eagles’ – which has all the ingredients of medieval struggle and bloodshed.

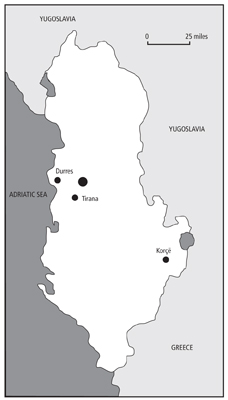

After the First World War, attempts by its immediate neighbours Yugoslavia and Greece to bite off respectively the northern and southern provinces were frustrated by US President Wilson’s policy of national independence. National integrity notwithstanding, Albania was the most backward and undeveloped country in Europe. Its mountainous terrain made the construction of a modern infrastructure of roads and railways virtually impossible, given the resources available at the time. Outside the capital, Tirana, and the main port, Durrës, much of the land remained the legendary ‘land of eagles’, where peasants laboured in medieval serfdom on estates owned by local lordlings, who pursued blood feuds known as

gjakmarrja

through the generations. Although a superficial semblance of parliamentary democracy existed in the main cities, even in the corridors of government buildings assassins lurked and claimed their victims. A member of a wealthy land-owning family, educated in Istanbul, Ahmet Muhtar Bej Zogolli was elected prime minister in 1922. In 1923 he was shot and wounded in the parliament building by a man whose death he arranged shortly afterwards. After another enemy was assassinated, Zogu – the prime minister had modified his name to make it sound more Albanian – and his followers were forced to leave the country by a leftist uprising. They returned to grab power with help from White Russian troops of General Pyotr Wrangel and the government of neighbouring Yugoslavia, which was rewarded for its help with some frontier adjustments. Surviving some fifty assassination attempts, Zogu was understandably paranoid and never seen in public unless surrounded by bodyguards. Preparation of all his food was in the hands of his mother, the only cook he trusted.

On 1 February 1925 Zogu’s political astuteness and ruthlessness saw him installed as Albania’s first president. Three years after that he was named King Zog I – modifying his name again to the Albanian for ‘bird’, so that his full title read ‘Bird I, King of the Sons of the Eagle’. As king, he reigned for eleven years, until driven out by Mussolini’s invasion of 1939. Having stashed at least $2 million in accounts at Chase Manhattan Bank, Zog and his Hungarian-American consort left the country, taking care to remove a disputed amount of portable valuables from the royal palace and bullion from the state treasury. Probably no one except their immediate household mourned their departure. In keeping with the prevailing political climate, on arrival in Britain they and their infant son – they had left within hours of his birth – were hailed as victims of fascism, which, in the commentary of a contemporary newsreel, was ‘defiling civilisation’.

However, during Zog’s presidency and reign some attempts at modernisation had taken place with the aid of Italian loans; serfdom was eliminated and Albanians

began

to think of themselves as citizens of a nation, rather than as subjects of a local lordling. To force these measures through against the resistance of landlords, Zog did not need to suspend civil liberties, because they had never existed in Albania, so there was nothing to stop him installing a nationwide secret police. With himself as supreme commander of the armed forces, his country was a military dictatorship, with all political opponents driven abroad, incarcerated or executed. So the scene was set for what happened after the Second World War, during which there was internecine fighting between the communist and other resistance organisations fighting at first the Italian occupation and then the Germans, who were finally driven out in November 1944.

The seed was sown in November 1941 when Yugoslav Communist partisan chief Josip Broz Tito was ordered by Moscow to send two party commissars into occupied Albania, where they formally established Partia Komuniste e Shqipërisë (PKSh) – the Albanian Communist Party – under the leadership of Enver Hoxha, a teacher from Korçë in the south-east of the country, near the Yugoslav border. He, ironically, had become a Communist when sent by his wealthy father to study in France in 1930, at the age of 18. Literally from the last day of the German occupation, Albania had its new dictator.

Albania after 1945.

The title of PKSh was changed in 1948 to Partia e Punës e Shqipërisë (PPSh) or Albanian Workers’ Party, but the name was unimportant since all other parties were swiftly banned. Unlike in the Central European satellite states, which had enjoyed strong commercial and cultural links with Western Europe before the war, there was no need to pretend democracy in a country that had never known it, but Hoxha took the title of prime minister, later adding those of foreign minister and defence minister – and governed what vaguely resembled a coalition until only the PPSh was left.