Dawn of the Unthinkable (35 page)

Read Dawn of the Unthinkable Online

Authors: James Concannon

Tags: #nazi, #star trek, #united states, #proposal, #senator, #idea, #brookings institute, #david dornstein, #reordering society, #temple university

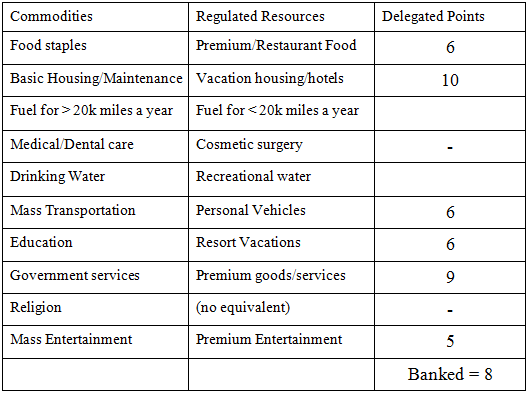

He looked at his chart and was satisfied

that it would suffice for the first rudimentary design of the

system. Each category’s ten levels would be ranked from one to ten,

and with ten categories of regulated resources, a person could

combine the levels in any combination up to fifty points. The goal

of each person would be to be awarded additional life points each

year through achievements to eventually reach one hundred points,

at which time he could “graduate” to the next level. The goal of

society would be to eventually raise the quality of each level,

starting with the bottom levels and working up. He thought he would

try to design several lifestyles to start using his variables. He

picked someone he knew intimately, himself, to decide what he would

want out of life and what he felt he deserved. Here was his

profile:

Age: 39 (Used only to project most likely

health needs)

Sex: Not relevant for determining “package”

of goods

Race: same as above

Marital status: Married

Number of children: 2

Major Life Achievement: Family, Ph.D.

Job Status: Senior Professional

Practicing Religion?: Yes (Used to allocate

donations for religious organization)

Salary Band: Upper Middle Class to Lower

Upper Class

Based on the proposal, his salary band

allowed him a few more options than lower levels, but not as many

as higher levels. For example, he might be able to choose a BMW,

but not a Ferrari. The voting would determine how many point he

would have to delegate for Regulated Resources. With a maximum of

100 points, he determined it was a safe bet to allocate himself 50

points for this exercise. He decided that housing was more

important to him than his vehicles. As there were ten levels of

housing in his mid-range lifestyle band (

That would be the third

level out of five

, he thought.), he would use ten points to get

the best house available in his band. That left him forty points to

spread over the remaining eight categories. He didn’t think he or

anybody in his family would need cosmetic surgery, so that left

forty points over seven categories. He didn’t really care much

about cars, so three points would get him comfortable but basic

transportation, times two so his wife could have a car, also. That

left thirty-four points. He liked premium food and classical music,

so he would allocate six on food and five on premium entertainment,

leaving twenty-three. He liked high-end stereo and personal

computers, and golfing, so nine points would be spent on premium

goods and services, leaving fourteen. He didn’t take many

vacations, being a bit of a workaholic, so only six would be

devoted to that, leaving eight in the “bank.” The banked points

could be used to raise the level of categories when the need or

desire arose. This way if he developed a taste for really fine

wine, he’s have some extra points to satisfy his desire.

He looked at the lifestyle package he had

designed for himself, and while it had limitations, it would be

acceptable if it improved everybody in America’s lot. It was of no

concern to him whether the people who had mansions and boats could

live with it, as it was not his job to convince them. He simply had

to design a computer system model that would show whether this

man’s idea was feasible, not whether it was good or bad, smart or

stupid. The relative certainty of feasibility appealed to Charlie

Lao’s precise brain. The fact that the idea of eliminating poverty

and racism in determining standards of living appealed to him,

also. While he prided himself as being an objective scientist who

let the facts take him where they may, he also knew that models

could be manipulated to show positive results. He decided that this

project might just get a little bit of a helping hand from him. He

was not sure if his father, who had been sent to an American

internment camp for Japanese during WWII, would approve of any

variations from the absolute truth. But Lao was American enough to

know how the game was played. And in Washington, people never let

the facts get in the way of a good story. He chuckled to himself.

If nothing else, this plan was a good story.

He hummed a merry little tune as he set

about designing the system. In this realm, he was a mighty general

who could make his troops of numbers march in a dazzling

formation.

Summer 1994

Wayne Cunningham saw the article. His mind

raced trying to imagine all the permutations of launching the media

campaign in this manner. He had wanted to try to hold back until he

had a read on which way Kennedy was going to go, but that was hard

considering how many Wobblies had been brought on board. He

suspected that one of them had caught this reporter’s ear and from

there on to Ryan. But he had hoped for a more auspicious roll out

than a lifestyle blurb.

Oh, well, what’s done is done

, he

thought, and now he had to plan how to make the best of it.

He decided that he better let Karen Strock

know, not because the senator’s name was mentioned, but just

because the story might start to heat up a little now. He called

her and had her look for the story in the

Times

, where

mercifully it hadn’t appeared. So unless people were really looking

hard for it, there probably wouldn’t be much notice. Of course,

there was no telling at this point as to how interested the

reporter was or whether he would keep trying to follow up.

Cunningham made a note to look into that. Strock was not overly

concerned; she said she had called the Brookings Institution and

they said they were about three weeks away from issuing their

report to Kennedy, and that he and her staff might take another

week or so after that to determine their response. She said the

best thing to do would be to lay low and to try not to have any

more press contacts. If the senator was going to go for it, they

would coordinate press releases from thereon and get the coverage

onto the serious news pages where it belonged. If he passed on the

idea, they were naturally free to pursue it in any way they saw

fit. From her perspective, she preferred to continue to examine the

idea without the prying eyes of the press.

Cunningham assured her they would do their

best to avoid media contact in the future, but that it was

difficult with so many people already aware. He promised to call if

anything else came up and hung up. Now he had to figure out what to

say to Ryan, who was probably worried about what he said and what

Cunningham would say to him and also what to do about Palma who was

trying to sit on some rather skittish colts. He also felt he should

clue the university in because it appeared that something was going

to happen, if not what he hoped. He would take care of Ryan first

and placed the call. Ryan answered, and Cunningham could hear the

tension in his voice.

He tried to put on his usual jaunty act by

saying, “Yo, professor, what’s up?” but Cunningham knew he was

nervous.

“Easy, big fellow, no irreparable harm has

been done. It wasn’t your fault that this guy was such a

third-stringer that he ends up in the lifestyle page. I already

called Kennedy’s office, and they’re not concerned but asked that

we not have any more articles come out until they’re done with

their review, which should take about another three to four weeks.

Do you know if this guy planned any follow up?”

Ryan answered, “I don’t know, but he seems

to sense something big here, and I don’t think he’s been allowed to

cover anything like this for quite a while. So I think he’s going

to be on my ass pretty good, but I’ll just keep telling him

nothing’s happening. What do you think of that?”

Cunningham paused and thought. “Okay, let’s

see how that works, but if he starts nosing around for more, let me

know. I guess we could throw him some more scraps and hope it

doesn’t appear in the gardening section.” They both had a laugh at

that, and Cunningham was pleased he managed to relieve his friend.

There would be enough stress soon.

He next called Palma and got the picture of

how the story was leaked to begin with. The leaker was a lonely guy

down south who nobody paid much attention to, and this was his

moment of glory. Not much could be done about that, but now Palma

was trying to walk a fine line between keeping the members’

enthusiasm high for being a part of something big while not letting

them actually do anything about it. As his people were mostly

independent cusses who weren’t fond of taking direction, this was

like trying to herd Jell-O uphill. He warned Cunningham that three

weeks was about the outside limit that he could keep the lid on,

and that gave them an idea. Three weeks would take them up to the

Fourth of July; why not shoot for announcing it then? With or

without Kennedy, they could announce the Wobblies’ participation

and see how people reacted. They could also test all of their

abilities to work as a team out in public because everything so far

had been out of view. Cunningham and Palma agreed that this was a

good idea, so they called Ryan and let him know. He agreed as well,

so it was set, and the three became very excited.

Cunningham was elated. This was a real, live

social experiment that he was right in the middle of, and it was so

much more thrilling to be a part of it than just relating it to

bored freshmen. Now he had some idea of how Dr. King felt, using

ideas to spur people to action. He wondered if he himself would go

down in history as a beloved revolutionary or as a despotic

crackpot? He grinned at the last image; people in general had such

a bad image of black people, was he going to make it worse? Oh,

well, he was in up to his nose now. No turning back even if he

wanted to.

Now would come the hard part—informing his

dean. He could hardly wait to see what his reaction would be; they

had granted him tenure very reluctantly. Now he would be proving

their worst fears about rampant activism. While there were no rules

against becoming involved in politics, business, or causes, it was

frowned upon as removing the objective basis one needed to be a

skilled observer and commentator on the modern condition. Some of

his fellow professors seemed to have an inordinate amount of free

time. They used stagnant syllabi, regardless of the changing times

and technologies, and employed grad students to grade papers.

Cunningham never took advantage of that perk, remembering his old

days of slave labor for maniacal professors who didn’t want to do a

scrap of work. Besides, some of the students’ work was quite

interesting and even innovative, as Ryan’s paper had shown.

Professors were expected to publish quite frequently, and in a

perverse way, this became more valued than the ability to teach.

While a well-taught course could enlighten thirty to forty-some

students a semester, a well-received book or article with the

university’s name attached could reach thousands. So from an

economic standpoint, the university became more interested in the

writing ability of the professor and was content to let the grad

student teach from the professor’s notes. It didn’t matter too much

to the school that the student was being short-changed by not being

exposed to the professor who helped give the school its good

reputation. Once they had his or her money, the actual content of

the education was not always quality controlled.

All this aside, they still paid him every

two weeks, so he had some degree of loyalty to the place. And now,

he was going to tell them he was trying to rearrange the fabric of

life.

This should go over like the proverbial flatuance in a

house of worship

, he thought. He went to the dean’s office and

checked in with his pleasant but overworked secretary to see if he

could spare him a few minutes. She glanced at the dean’s

appointment book and said if he could be brief, he could sneak in

at the end of the phone conversation he was on. Cunningham lied and

said that he would be brief and sat down to wait. On the waiting

room coffee table were education magazines booming the latest

teaching methods or professor’s accomplishments. He had the feeling

he was going to blow that category wide open.

The dean got off the phone and came out of

his office for a quick stretch and cup of coffee. His eyes widened

in surprise when he saw Cunningham sitting there, as they did not

usually have many one-on-one meetings. He tried to hide his

discomfort, but Cunningham caught it, as he had seen it on so many

white faces in his life.

He put on a false bonhomie, saying heartily,

“Wayne, good to see you, man. Our paths don’t cross much, do they?

How are you doing? How’s the wife and kids?”

Cunningham could see he could not remember

whether he even had a wife and kids, let alone what their names

were. Cunningham didn’t care; he would never count this man as a

friend, just one of the facts of his life. He replied, “They’re

fine, Harry. Growin’ like weeds, and Nancy’s fine.” He said this

last to test his theory about the dean not remembering his wife’s

name.