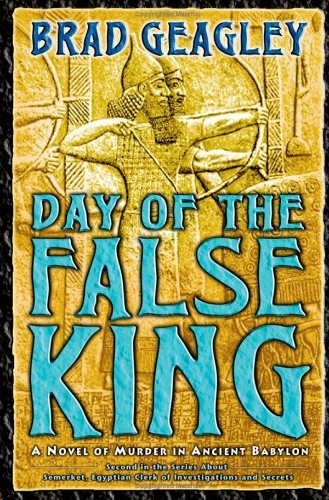

Day of the False King

Read Day of the False King Online

Authors: Brad Geagley

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary, #Genre Fiction, #Historical, #United States, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Contemporary Fiction, #American, #Literary, #Historical Fiction

Brad Geagley

For Randall R. Henderson

DAY OF THE FALSE

KING

continues the story of Semerket, Egypt’s

clerk of Investigations and Secrets. The time is approximately 1150

BCE,

and the conspirators who plotted the overthrow of Pharaoh Ramses III

have been tried and executed. But the old pharaoh has succumbed to the

wounds inflicted by his Theban wife, Queen Tiya; it is his first-born

son who now rules Egypt as his chosen successor, Ramses IV.

Day of the False King

takes place

mainly in the city of Babylon (ancient Iraq). Geographically placed at

the center of the Old World, where East literally meets West, Babylon

was the crossroads for conquering armies and adventuresome merchants,

and the prize of dynasts. From cruel tyrants to far-seeing visionaries,

an ever-changing set of rulers have claimed Babylon’s throne as their

own. But they were not god-kings as in Egypt; in fact, there was no

term for “king” in any of the Babylonian languages. Instead, they were

called simply “strong man” or “big man.” Then as now only martial

strength determined who ruled. Strangely, or perhaps inevitably, the

rights of the individual were first codified and set down as laws here.

Around the time that

Day of the False

King

occurs, the Middle East is undergoing — just as it is today —

a tortuous, protracted transformation. The old regimes have vanished,

setting the stage for the aggressive emergence of the new nations of

Phoenicia, Israel, and the Philistines; it is the fourth of these new

peoples, the Assyrians, who will achieve dominance in the years ahead.

Babylonia in particular has suffered a

series of cataclysms. The old Kassite Dynasty, themselves invaders from

the north, has been toppled. The nation of Elam (soon to be known as

Persia) has launched a massive war to conquer Babylonia from the

southeast. Native tribes in the country also see this moment as their

own chance to evict the foreigners and re-establish a dynasty of their

own.

Into this roiling alchemy Semerket’s adored

ex-wife, Naia, is thrust. She and Rami, the tomb-maker’s son, have been

banished to Babylon as indentured servants — punishment for their

accidental roles in the Harem Conspiracy against Ramses III.

As in the first novel, most of the events in

Day of the False King

actually happened, and many of the

characters actually existed. The Elamite invader King Kutir and the

native-born Marduk truly vied for the throne of Babylonia. There really

was a festival called Day of the False King, where the entire world

turned upside down for a day, when slaves ruled as masters — when the

most foolish man in Babylon was chosen to become king.

Brad Geagley

Alas my city! Alas my house!

Bitter are the wails of Ur

She has been ravaged

Her people scattered.

— The Lament for Ur,

Traditional Sumerian poem

Babylon

WAKING WITH A SHARP CRY,

HE FELT HIS

heart thump madly before he realized

that he was on his pallet in his brother’s house. Once again, he had

dreamed of his wife, Naia, slaughtered before the eyes of his wandering

night’s spirit. He sat up in the dark, rubbing his forehead. Every time

he had the dream, his old wound stung.

Throwing his mantle over his shoulders, he

slipped from the courtyard gate. He had taken to walking the Theban

streets late at night when he could not sleep, which was most nights

now. Turning from the Avenue Khnum, where the bonfires of Amun’s Great

Temple blazed, he slipped into a dank and twisting alley behind a

riverfront warehouse. Picking his way through the rot and refuse, he

came at last to a tavern. The sign hanging above its door depicted a

hippopotamus besieged by hunters.

It was very late and many of the patrons

were snoring over their cups. The Wounded Hippo was a venerable

dockside haunt, centuries old, and its brick walls were crumbling to

pieces. Unfortunately, the current owner’s apparent devotion to the

antique did not extend to the vintage he served.

He trod silently to his usual corner and

signaled the tavern’s owner.

“Wine,” he said. “Red.”

At the hearth, the innkeeper poured some

wine into a terracotta bowl and gave it to his serving wench. “See that

man over there?” he asked, keeping his gruff voice low. The woman was

recently hired, and unfamiliar with the tastes of the tavern’s regular

patrons.

She turned her head discreetly, whispering

in the same guarded tone, “A gentleman!” Her posture perceptibly

straightened so that her breasts might be displayed to better advantage

beneath her tight linen sheath. “What’s he doing

here,

I

wonder?”

The innkeeper ignored the unintentional slur

to his establishment. “Every night he comes in and wants the same

thing.”

“Well, that’s hardly strange — not much to

choose from, is there?” The wench laughed, which she often did these

days, proud of her new teeth made of elephant ivory and wired into her

mouth with copper bands. “I mean, it’s either white or red, now, isn’t

it?”

“That’s not the point.” The man’s voice fell

to a whisper. “He never drinks it.”

The woman caught herself in midchortle. The

idea of a man coming into a tavern and not drinking struck her as odd,

somehow, almost obscene. “You’re joking,” she said.

“May my Day of Pain come tomorrow if I am,”

the innkeeper said. “Just stares at the bowl all night, and never once

brings it to his lips.”

The woman peered suspiciously at the man.

“He’s not a ghost, is he? They say ghosts can’t eat or drink, but still

they pine for it terrible.” She shivered. “I won’t serve ghosts.”

“He’s alive all right — though Egypt

would’ve been better off if he wasn’t. A ‘follower of Set,’ he is. He’s

the one accused all them at the conspiracy trials last year.”

“That’s

Semerket?”

The innkeeper nodded. They stared.

Semerket’s aggravated voice abruptly cut

through the room. “Must I wait for the grapes to be harvested?”

The innkeeper looked down at the bowl still

clutched in the wench’s hands. “Better take it to him. Don’t want my

name on any list of his.”

The wench swept her mass of braids away from

her face and crossed the room to where Semerket sat, her generous hips

swaying as she walked. She placed the bowl at his side.

“Your wine, my lord.”

At her unfamiliar voice, his head snapped

up. She was struck by the sudden tense collision of emotions on his

slim face. His eyes, glittering dangerously in the firelight, were the

blackest she had ever seen. He was not handsome, but far from ugly. She

dropped her eyes before his powerful stare, and the woman was surprised

to feel something unexpectedly warm flush through her loins.

“You’re new,” Semerket said, handing her a

copper snippet. It was not a question.

The wench bobbed her head, and the wax beads

woven into the ends of her braids clicked together softly.

Semerket looked away, his black eyes going

opaque. Still the woman lingered a bit, collecting the empty bowls

strewn around the rug. He did not appear to notice her.

“My lord?” she whispered at last.

He looked up, surprised to find her still

there. “What?”

“I don’t mean to pry, but — but my master

over there says — well, he tells me that every night you order wine,

but that you…”

“But that I never drink it.” Annoyance

flickered behind the obsidian depths as Semerket glanced in the

direction of the innkeeper. “I wasn’t aware he found me so fascinating.”

Though his voice was cold, the woman

persisted. “I thought you was a poor spirit, maybe, some sort of ghost,

now, didn’t I? But up close, I see you’re a fine, strong man. Very

alive, indeed. So why do you not drink?” She smiled at him

encouragingly.

“My wife doesn’t want me to,” he said dully.

“And I promised her…something…”

“Well, if you don’t mind me saying it, what

you need is a more forgiving woman.”

He grabbed her wrist, and her words ended in

a tiny yelp. She gasped at the strength in his grip as he pulled her

down so that her eyes were level with his. In the firelight his face

was haggard and drawn, his expression tormented.

“I need the wine because I know if I can’t

deal with my life any longer, one little sip and the gods grant me a

merciful release. Do you understand now? It’s a way out.”

She nodded, her eyes wide, the ivory

nervously glinting. “Yes, my lord. Yes. It does a body good to get out

now and then. I understand. Truly.”

The odd lights in Semerket’s eyes suddenly

extinguished, and he let go of the woman’s arm. She comprehended

nothing.

Rubbing her wrist, she retreated again to

the hearth, never to come near him again that night. Semerket hardly

noticed. He gazed instead into the shadows, as if looking for

something. It was very close now, he knew, the thing that sought him.

He felt like some helpless rabbit, spellbound by the cobra’s approach.

For a year, he had sensed it coming. Lately

the feeling had become worse. Rarely did he sleep through an entire

evening without seeing his banished wife, Naia, slain by a spear’s

thrust. The dreams were a warning, he believed, some intuitive

communication he had received from her. Perhaps she was in some kind of

danger in Babylon; perhaps she needed him. It might be that she was —

He clenched his eyes tightly, rubbing at his

brow, refusing to consider that obscene possibility.

At long last, through the doorway, he saw

that the night was turning from black to gray. He rose, another evening

gone. Outside, shrill birdsong poured from the reeds and grasses at the

Nile’s edge, and from the Temple of Thoth came the distant barks of the

sacred baboons heralding Ra’s approaching solar barque. He stood at the

river’s edge and closed his eyes, inhaling deeply.

The air was clear on the river. The Nile had

only recently receded, leaving its yearly gift of silt upon the land.

The odor of rich black earth rose in his nostrils. Tassels of sprouting

emmer wheat and flax fringed the distant fields with a delicate green.

It would be a good harvest this year, he thought, if the gods did not

afflict the crops with locusts or snails.

The food vendors soon appeared from the dark

alleys to set up their stalls on the concourse. When the smells of

frying onions and spiced fish began to scent the boulevard, he turned

and walked back to his brother’s house. Nenry was the mayor of Eastern

Thebes and occupied an estate near the Temple of Ma’at. Semerket’s

fretful mind was a void, for once, and he was unprepared for the sight

that met him at his brother’s gate.

A cohort of Shardana guards waited in the

alley. They were Pharaoh’s elite northern guard, composed of Egypt’s

former enemies, the Sea Peoples. An empty sedan chair waited with them.

It was no modest equipage, for eight liveried attendants wearing

Pharaoh’s colors carried it.

Semerket saw that Nenry and his wife, Keeya,

stood at the gate. From their anxious expressions, he sensed that the

news was not good. Keeya clutched Huni to her chest, the child Naia had

left behind in Egypt for Semerket to raise. Even the infant’s dark eyes

were full of fright.

“Here is my brother at last,” Nenry said,

his face wreathed in nervous tics.

The Shardana chief turned as Semerket

approached. “Lord Semerket?” he asked.

Semerket nodded mutely.

“Pharaoh requests your presence at Djamet

Temple.”

Semerket swallowed, trying to find his

tongue. “May I…may I know why?”

“There is a message for you, I’m told — from

Babylon. Pharaoh wants you to come immediately.”

He would have fallen if the guards had not

leapt to catch him. As they eased him into the carrying chair, he cast

a stricken glance at Nenry and Keeya. He felt Nenry’s hand squeeze his

shoulder as the chair was lifted high by the bearers.

As she held Huni for him to kiss, Keeya

whispered into his ear, “The gods go with you, Semerket.”

It was too late for gods, he knew; the thing

he feared had come. Resolutely, he turned his face to Djamet Temple.

SEMERKET STOOD at the grated

window in Pharaoh’s private chambers, straining to make out the blurred

and water-stained words written on a piece of brittle palm bark. The

first ones he managed to pick out were ominous:

…

attacked by Isins.

He had no idea what or who Isins were — or

even who had written the letter. The next few glyphs, smudged beyond

recognition, offered no help. He could make out only those that spelled

these words:

…

the house of Menef to

…

Prince

of Elam

…

Naia

…

His breath caught when he saw the name he

cherished actually written down. The only glyph he could further

distinguish, and that with difficulty, was the most chilling of all —

slain.

Then, at last, the signature, smudged and

barely legible.

Rami.

He raised his head. Surrounded by his

scribes and servants, the fourth Ramses sat on a thronelike chair at

the end of the room. Beside him was another man, a foreigner. Though it

was late winter and the temperature was climbing every day, Egypt’s

king had wrapped himself in a heavy, embroidered cape of red wool.

Charcoal braziers were placed everywhere about the room to warm it.

“Does Your Majesty know the contents of this

letter?” Semerket asked.

Pharaoh nodded, and gestured to the

foreigner, who also sat in a chair. “My cousin Elibar, here, brought it

to me last night. We read it together — or as much of it as we could.”

Semerket, surprised, looked closer at the

other man, and noticed that Pharaoh and the foreigner indeed shared a

physical likeness he had not appreciated at first — the same slim,

prominent nose; the pale eyes and skin. Indeed, though the stranger’s

long hair and beard had turned to gray, their hue had once been the

same russet that characterized all the Ramessid family. He must be

related to the king’s Canaanite mother, Semerket thought.

Ramses drew a breath to speak again, but

instead began to cough. A faint sheen of sweat erupted on his forehead

and he pressed a kerchief to his lips. Semerket noted the instant

concern that flared in Elibar’s eyes. With a wordless gesture, the

hovering chamberlain directed a servant to remove the soiled kerchief

and bring another. Though the room’s light was dim, Semerket thought he

saw a faint tinge of pink froth staining the cloth before the slave

hastily folded it. Elibar himself filled a goblet with wine and held it

to Pharaoh’s lips.

When he had finished drinking, Ramses sat

back on his gilded chair, weakly mopping his brow with a fresh

kerchief. “Now,” Pharaoh’s voice was stronger, “you will no doubt want

to ask my cousin about that letter you hold.”

Without pleasantries, Semerket nodded and

began to speak. “How did you come by this letter, lord? And when?”

Elibar answered slowly, taking time to

consider his words. “A caravan entered Canaan from Babylon a fortnight

ago. This Rami of yours had given the letter to the caravan’s master to

bring to Egypt, or to pass to another merchant who would.”

Though Elibar spoke an excellent Egyptian,

his voice was so deep and oddly inflected that Semerket had to watch

the man’s lips to determine the words he actually spoke.

“In my own land people know that I’m

Pharaoh’s cousin — not always to my advantage, I might add — so the

letter was brought to me. I recognized your name at once, for my aunt,

Pharaoh’s mother, had written to me about how you rescued my cousin

from the conspirators. I hurried here, knowing of his majesty’s regard

for you.”

Semerket could not conceal his

disappointment. “Then you weren’t the one to actually see the boy?”

Elibar shook his head.

“Is he still alive? Did the man indicate —?”

“He only said that he was very sick — that

he suffered from some kind of head injury.”

“Did he mention where Rami might be found?”

“Well, there I can be of more help to you.

He told me he met the boy on the outskirts of Babylon, at an oasis near

a ruined estate. The man used a stick to draw an outline of Etemenanki

in the dust, making a circle around it —”

Semerket canted his head, not sure that he

had heard correctly, “Etemenanki, my lord?”

Elibar paused in his narrative. “The devil

Bel-Marduk’s abode, yes — the ziggurat at Babylon’s center. The man

took a stick and —”

The word caught Semerket by surprise, and

before he could stop himself, he asked,

“Devil?”

Bel-Marduk was the Babylonians’ name for the

god that Egyptians called Amun-Ra. Never before had Semerket heard the

father of the universe referred to as a devil, and he felt almost

superstitiously affronted by Elibar’s casual blasphemy. Quickly he made

the holy sign in the air.