Dead Man's Puzzle (20 page)

Authors: Parnell Hall

Harvey Beerbaum opened the front door in his pajamas and robe. He’d clearly been in a deep sleep and looked utterly bewildered.

“Cora! My God! What’s happened?”

“Nothing, Harvey. I need your help.”

“You need my help?”

“Yes, I need you to solve a puzzle.”

“You need me to solve a puzzle?”

“If you’re going to repeat everything I say, this is going to take a long time.”

“What time is it?”

“It’s puzzle time, Harvey. Are you going to ask me in?”

“I’m in my pajamas.”

“Of course you are, Harvey. It’s the middle of the night.”

“What?”

“Harvey, trust me. I’ve lived through scandals in my day, and this doesn’t measure up. The police could catch us doing crosswords at the kitchen table, and it wouldn’t even rate the

National Enquirer

.”

“National Enquirer?”

“You’re doing it again, Harvey. Come on. You wanted in on the big time. Chief Harper brought you a puzzle. It was gibberish. I got one that may be the real deal. If it is, I’ll give you credit. Come on, whaddya say?”

“You want me to solve a puzzle now?”

“At last, a meeting of the minds. Yes, Harvey, I want you to solve a puzzle now.”

“Why?”

“Because Sherry and Aaron are chasing lions.”

“What?”

“Wanna risk a light, or are you afraid the neighbors will know you’ve got company?”

“It’s none of their business.”

“Attaboy!”

Harvey flicked on the light. Cora swept ahead of him to the dining room table, sat in one of his rattan wicker-back chairs.

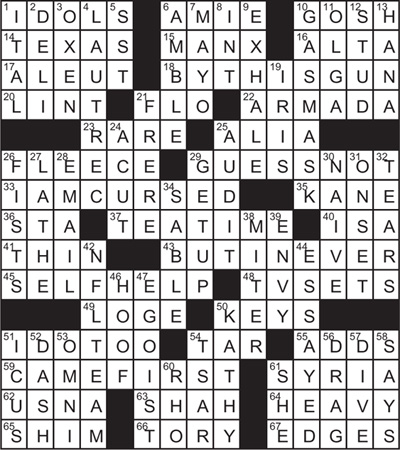

“Here you go, Harvey. It’s a fifteen-by-fifteen. I’m giving you six minutes because you’re not awake. Whaddya think?”

Cora spread the puzzle out on the table.

“Where did you get this?”

“I’m not at liberty to say.”

His eyes widened. “Really?”

“Sound a little more interesting? Come on, let’s solve this sucker.”

Harvey got a pen, rested the puzzle on a magazine so as not to harm the tabletop.

“You do it in pen?”

“Of course. Don’t you? Oh, that’s right.”

“Go on, Harvey, do your stuff.”

With Cora watching, Harvey whizzed through the puzzle. He was done in four and a half minutes. While he was finishing up, she had already read the theme answer.

“ ‘By this gun I am cursed, but I never came first.’ ”

“Gun. What gun?”

“See, Harvey? Isn’t that a little more interesting?”

“Do you know what it means?”

“Not yet. But I’m getting ideas.”

Chief Harper’s voice was groggy. “Yeah?”

“I’ve got it!” Cora said.

“Got what?”

“A theory!”

Harper rolled over, looked at the clock. “You called me at three-thirty in the morning with a theory?”

“It’s a good one.”

“What is it?”

“I’m not sure.”

Harper controlled himself with an effort, said, “Call me when you

are

sure.”

“Okay, but you gotta do something for me first.”

“What in the world are you talking about?”

“The convenience store robbery. The one Overmeyer had the gun for. That’s what he was concerned with all along. Which is good, because if the gun wasn’t involved, I was going to be mad.”

“Cora.”

“The witness who survived. Found lying on top of his buddy bleeding into a sewer drain.”

“What about him?”

“First thing tomorrow morning, call the Alabama police and get ’em to pull that grating up.”

“What?”

“It’s a storm drain, right? A grate with a drain below? Have ’em pull up the grate and search the drain.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No.”

“It’ll be full of water.”

“So send a diver down.”

“I don’t mean like that. It’ll be like ten feet deep with a foot of water in the bottom.”

“So have someone climb down and search it.”

“Why?”

“Because no one ever did,” Cora said, and hung up.

Chief Harper was madder than a wet hen. Cora had never actually seen a wet hen, but she figured they must be pretty mad to rate their own saying.

“I hope you know what you’re doing,” Harper said grumpily.

Cora plopped a paper bag on his desk. “Here.”

“What’s that?”

“Coffee and a muffin. Raisin bran. Great for a cranky old sourpuss. Straighten you right out.”

“I don’t know whether to thank you or arrest you.”

“You call Alabama?”

“Yeah.”

“And . . . ?”

“They weren’t happy to hear from me. Imagine that. Would they mind climbing into a sewer drain on account of a fifty-year-old convenience store robbery? I don’t know why they didn’t jump at the chance.”

“Did you remind them you have the gun used in the robbery?”

“Yeah. They were thrilled. Seein’ as how the guy who owned it is dead. And his accomplice is dead. The case itself was dead until I opened it. Trust me, there’s nothing cops like more than opening a fifty-year-old case they thought they’d never see again. A case they couldn’t prosecute if they wanted to.”

“Murder never outlaws. There’s no statute of limitations.”

“There is when the murderer is dead. Try and work up some enthusiasm for prosecuting the late Mr. Overmeyer.”

“I can imagine.”

“I got a police chief in Alabama doesn’t think I’m the cat’s meow. Thinks I’m a major pain in his fanny. For even

reminding

him of a fifty-year-old case. ‘Take off a storm drain and climb down in a filthy sewer pipe? Thought you’d never ask.’ ”

“Drink your coffee, Chief.”

“It’s gonna take more than coffee and a muffin to make up for this one. I made the phone call on your assurance that I should. Without making you explain. Not that I

could

make you explain, but I mean insisting on it. All I know is you mumbled something that made no sense at all at three in the morning, and doesn’t seem to make any more sense now. Since I did, you wanna give me some hint why I’m laying my reputation on the line?”

“I can’t guarantee results, Chief. Fifty years is a long time.”

“Now you tell me.”

“But I’d never forgive myself if I didn’t look.”

“Are

you

wading around knee-deep in sewer water? You’re not looking.”

“You’re not either.”

“And don’t think I won’t be reminded of the fact.”

The phone rang.

Harper scooped it up. “Harper here.” He listened a moment. Blinked. “Are you kidding me? Give me that again. . . . No, I can’t tell you why. I gotta do some checking on this end. . . . Because I don’t

know

why. I’ll put this together with what I got and see how it adds up. I’ll get back to you as soon as I do.”

Harper slammed down the phone.

“Alabama?” Cora said.

“Yeah.”

“They take off the storm drain?”

“Yes, they did. And whadda you think they found?”

“A three fifty-seven Magnum.”

Chief Harper’s coffee cup stopped halfway to his mouth. “How the hell did you know that?”

Cora smiled.

“Some days you get lucky.”

Cora Felton twirled the gavel, smiled down from the bench. “We are here for the reading of the will. Becky Baldwin’s law office is too small to accommodate everybody, so Judge Hobbs has been kind enough to loan us his courtroom.

“Please note that the media are here.” Cora gestured to the Channel Eight News crew. Rick Reed’s black eye had gone down. He had a Band-Aid on his chin, the little round kind that covers a shaving nick. “They may film if they’re not intrusive. The minute they are, they’re going out.

“Also note the presence of Chief Harper, who is here to maintain order. In the instance that some heir is not satisfied with what he or she gets, the chief will be happy to escort them to a holding area where they can think it through without disturbing the others. Because, in point of fact, this whole inheritance has dragged on too long. Understandable, give or take a murder or two. Still, with so many heirs forced to remain in town, the situation is sticky at best, and I’d love to get it resolved before anyone else is killed.”

Cora looked them over. “To date, none of the heirs have been murdered. This is too bad. With an inheritance at stake, you’d think the heirs would want to bump each other off, in order to increase their cut. It’s a nice clear motive. In Agatha Christie I think it’s called a tontine. The survivors inherit more by voting the others off the island.

“One has already left. Miss Cindy Barrington.” Cora read the name off a list to avoid calling her the Hooker. “She was seen boarding a bus. Which could mean she was the killer making good her escape, but in that case it’s hard to see how she could have benefited from her crime. I think it’s far more likely she was just a wannabe heir, throwing in the towel and abandoning a rather spurious claim.”

Cora surveyed the remaining heirs. With the exception of Harmon Overmeyer, they looked decidedly uncomfortable.

“We’re all here for the reading of the will. Except there

is

no will. Mr. Overmeyer died intestate. His property is to be divided amongst you. I am to do the dividing. I have been appointed Solomon. Mr. Overmeyer has trusted in my wisdom to see that the proper inheritance is distributed to the proper heirs.”

“What do you mean, distributed?” Bozo demanded. “If there’s no will, each of us has just as much claim as the other.”

“Like hell,” the Cranky Banker said. “You and your wife get one share. Just like everybody else. You don’t get two.”

“I don’t see why not.”

“This is something to take into account,” Cora said. “The other consideration is what we do with Cindy’s share.”

“She left, she forfeited it,” Cruella said spitefully.

“Who gets the cabin?” the Geezer demanded. “Surely we can’t all get the cabin.”

“No, you can’t. You’re virtually forced to sell it. And it’s not going to bring much. It’s a small piece of land with a ramshackle cabin. Whoever buys the cabin is going to have to demolish it, and no one is going to buy such a small piece of land if they have to do that. They’d buy undeveloped land and start fresh. Which means you have one buyer who can more or less dictate his own terms. Mr. Brooks would love to get that eyesore out of his sight lines. How much would he love to? I would imagine he’d make a reasonable, though not exorbitant, offer on the cabin, and wouldn’t be inclined to raise it. Is that the situation, Mr. Brooks?”

Brooks heaved a sigh. “I don’t know.”

“Well, that’s what you told Chief Harper.”

“That was before my wife died. Now I might sell my place instead.”

That statement set off a rumbling and grumbling from the heirs.

Cora banged the gavel. Smiled. “God, I like doing that. Now, if we could have no more of this. That answer may not please you, but it’s certainly an answer. Mr. Brooks can sell his place if he wants. In which case he won’t buy the cabin, and you get squat. I’m sorry, but this meeting isn’t to make people happy, it’s to sort things out.”

“What about the other neighbor?” the Cranky Banker demanded.

“The neighbor on the north side is Mr. Arlington. There’s a forest grove between the cabin and his house. He can’t even see the cabin. The forest is all on his land, so no one can develop it. As far as he’s concerned, the cabin might as well not exist. And he’s not going to buy it just to upgrade the neighborhood. Is that your position, Mr. Arlington? You didn’t kill Mr. Overmeyer just because he was a lousy neighbor?”

Mr. Arlington was an outdoorsy type, in a fisherman’s vest and hat. “As I told the police, I have no interest in the case.”

“I quite agree. You have no motive at all, and could care less about any of this. In a murder mystery, that would make you the most likely suspect.”

“Hang on,” Cranky Banker said. “If there’s no will, how do we inherit?”

“I told you. It’s entirely at my discretion. You get what I give you.”

“That’s not fair.”

“I think you’ll find it is. I think you’ll find I am totally, almost scrupulously fair. I am, in fact, eager to dole out the inheritance. Let us clear the air. More to the point, let us clear the heirs. We have to deal with them first. Mr. Weston, stand up.”

Bozo stood up.

“Here we are, ladies and gentlemen. Look at that. Do you see his red hair? Can’t miss it, can you? And Mrs. Weston. Could you stand beside him?”

Cruella stood up.

“There you are. Straight out of the Addams Family. What a lovely couple. You have to ask yourself, Why in the world would anyone look like that?”

Cora spread her arms, looked around the courtroom. “This is a toss-up question, anyone can answer, just buzz right in. . . . No one? . . . Okay. Well, here’s the answer. Why would anyone want to look like that? Because they

don’t

. They don’t. And they don’t want to be recognized for how they actually look. Because they’re phony heirs, just hoping to cash in on the dead man’s estate. That’s why they look like they want to run. Okay, sit down, take it easy. No one’s arresting you yet.”

Cora twirled the gavel. “The thing that troubled me from the start is why are all these heirs in town? Particularly if some of them are bogus. To answer that, we have to look at the murders. I’ll take the third one first. Like they used to do on the old quiz shows. ‘I’ll take the third part first, Jack.’ Of course they were fixed.” Cora grimaced. “Oh, hell, I just dated myself again. I was a wee slip of a girl, bouncing on my daddy’s knee, had to have it explained to me. Where was I? Oh, yes. The third murder. Preston Samuels. Came to me right after the first murder was announced. Told me about a stock-pooling agreement, something a relative had been involved in with Overmeyer back near the dawn of time.”

Cora looked around. “Why did he do that? Well, it served two purposes. One, it gave a reason for Overmeyer to be killed. Two, it created the impression of untold wealth and accounted for the presence of so many heirs.”

She tapped the gavel into her palm. “Now, who would want to do that? Who would want a bunch of heirs traipsing around, falling all over themselves in the quest for untold millions? Who might have wanted a bunch of suspects on hand to mask his murder? You notice I say ‘his’ in the inclusive, nonsexist way that allows for the possibility of a woman, so that I don’t have to keep saying ‘he or she.’

“Now, who do we have on hand who is

not

an heir, who has a motive in the murders?

“We’ll take the second murder next. Who had more motive to kill Mrs. Brooks than Mr. Brooks?”

George Brooks lunged to his feet.

“There he is now. About to protest his innocence. A totally pointless gesture, Mr. Brooks. That’s exactly what you’d do if you were innocent

or

guilty. So don’t waste your time.”

“Damn it—”

“He’s indignant. I’ve impugned his motives and insulted the memory of his wife. If he’s banging a sweet young thing from Greenwich Village, it’s entirely coincidental.”

Cora put up her hand like a traffic cop to stifle Brooks’s indignant response. “Moving on. Anyone else have a motive that screams to high heaven? Yes. Harmon Overmeyer. The legitimate heir. He who will prevail when all others have fallen by the wayside. If he killed his great-uncle to get the cash, everything else could follow. Juliet Brooks sees him in the house, he has to silence her. For reasons of his own, he has to silence Preston Samuels. He got here before the other heirs, found himself alone, didn’t like that situation, and saw that they were summoned.

“How did he do that? Perfectly easy. He posted Overmeyer’s obit on the Internet. Which assured the arrival of professional heirs. Vultures who scan the obituaries for people who die with few or no relatives. ‘Survived by his great-nephew’ is a dead giveaway. No one’s apt to be able to prove you’re

not

related to the dear departed.

“So Harmon gets a bunch of scavengers here to mask his own movements in rifling the estate.”

“Now see here—”

“Yes, yes, Mr. Overmeyer, we note your dissent. Like Mr. Brooks, you’re innocent. Give it a rest.”

Cora stared him back into his seat.

“But why does he have to do that? Why rifle the estate if he’s going to inherit anyway?”

Cora smiled. “Working backwards, we have reached the first murder. The murder of Overmeyer. Overmeyer died in possession of a gun used in a convenience store robbery in 1954. One might ask, why did he save a gun that long when it could incriminate him? But the fact is, he did, and with the discovery of the gun comes the implication that if Overmeyer was guilty of that robbery, he probably participated in several other related crimes. Which would eventually amass a goodly amount of cash.

“If the money were discovered as part of the estate, it would open speculation on the one hand, and involve a huge inheritance tax on the other. Which would explain why the heirs would want to eliminate the middleman and seize the cash before probate. Wouldn’t that be the prudent course of action, Mr. Overmeyer?”

“I assure you—”

“That was a rhetorical question. Anyway, let’s consider the decedent, Herbert Overmeyer. Did he have a reason for living like a hermit in his little cabin in the woods?

“Yes, he did.

“The convenience store robbery was a homicide. Actually, a double homicide. The proprietor was shot with a three fifty-seven Magnum. Two witnesses were shot with a thirty-two-caliber Smith and Wesson revolver. One of them died. Which makes each of the perpetrators guilty of murder, accessory to murder, murder in the commission of a felony, etc., etc., etc., lock ’em up and throw away the key.

“So it is not surprising to find Mr. Overmeyer keeping a rather low profile.

“So, what changed things?

“Overmeyer’s partner in crime died. Rudy Clemson. He was a war buddy, been in Korea together, served in the same platoon. Got out of the army and hit the road.

“But not right away. Not before Rudy Clemson racked up an impressive string of felony arrests. After the last of which he skipped bail when faced with a likely ten to twenty-five.

“Anyway, he died.

“Overmeyer took it to heart. There is every indication that, as he saw his own life coming to an end, he felt the urge to clear his conscience and make amends. I have every reason to believe that if Overmeyer had lived, he had actually decided to confess.”

Harmon Overmeyer sprang to his feet. “Oh, come on. If you’re going to tell me his estate is ill-gotten gains and I have no title to it, I’m going to fight. You have no proof whatsoever.”

“Actually, I do,” Cora said. “Overmeyer left a clue behind. A crossword puzzle. Unfortunately, it was gibberish. A nonsense rhyme. ‘At noon I can not be done. So I should try to at one.’ Harvey Beerbaum solved it for Chief Harper. He understandably did not act on it. Why? Because it was meaningless. Harvey showed me the puzzle, and I quite agreed.

“Then Barney Nathan autopsied the body and discovered poison. At which point, I took another look at the puzzle. And had an epiphany.

“You ever read a sonnet? By Keats or Shelley or one of those boys?” Cora looked around at the sea of perplexed faces. Shrugged. “Yeah, I know. I prefer

American Idol

myself. I had to read ’em in college. And you know what? They cheated. They’d rhyme

glance

with

utterance

. Or

fiend

with

bend

. Even Shakespeare, in his most famous sonnet, ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day,’ rhymes

temperate

with

date

. Come on. Just ’cause it ends in the same letters doesn’t mean it rhymes.”

Cora smiled. “See what I mean? Same thing with Mr. Overmeyer. ‘At noon I can not be done. So I should try to at one.’ No. The poem

doesn’t

rhyme. The second line is ‘So I should try to

atone

.”

Cora spread her arms. “So you see, judging by the crossword left by his body, there is every reason to believe that Overmeyer intended to confess to the crime.”

The Geezer sprang to his feet. “Nonsense! That’s a ridiculous leap of logic! There’s no reason whatsoever to think such a thing!”

“Oh, but there is. Sit down, and I’ll tell you how I know.”

Cora waited for the Geezer to subside.

“The key to the whole thing was Overmeyer’s partner. Rudy Clemson. Overmeyer was responsible for his safety. He was, in fact, the one thing standing between Rudy and prison. Nothing had ever connected either of them in any way with this convenience store robbery. And after such a long time, there was no reason to believe that anything ever would.

“Unless Overmeyer confessed.

“If Overmeyer confessed, it would be a simple job for the police to figure out who his accomplice was. Just as Chief Harper had no problem figuring it out once Overmeyer’s connection to the crime was known. A confession by Overmeyer would essentially doom Rudy Clemson.

“Which is why he kept quiet until his partner died. Rudy Clemson died last year in Georgia. Why did Overmeyer wait so long to act? It probably took a while before he found out. The death of a derelict would not be front-page news. But once Overmeyer

did

find out, he immediately resolved to come clean. To go public with the secret that had been burning inside of him all these years. That would not let him rest or lead a normal life. That probably was the reason he lived alone, a virtual hermit in a run-down shack.