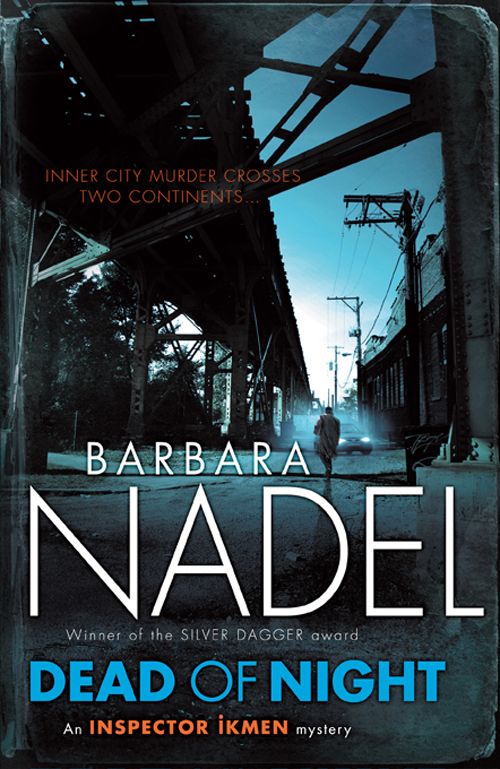

Dead of Night

Authors: Barbara Nadel

Barbara Nadel

Copyright © 2012 Barbara Nadel

The right of Barbara Nadel to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2012

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN : 978 0 7553 7167 9

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

To the great city and great people of Detroit. Also for

Jim Reeve and his big, beautiful view of the Shard of Glass

Çetin İkmen

– middle-aged İstanbul police inspector

Mehmet Süleyman

– İstanbul police inspector, İkmen’s protégé

Commissioner Ardıç

– İkmen and Süleyman’s boss

Sergeant Ayşe Farsakoğlu

– İkmen’s deputy

Sergeant İzzet Melik

– Süleyman’s deputy

Dr Arto Sarkissian

– İstanbul police pathologist

Tayyar Bekdil

– Süleyman’s cousin, a journalist in Detroit

Lieutenant Gerald Diaz –

of Detroit Police Department (DPD)

Lieutenant John Shalhoub

– of DPD

Lieutenant Ed Devine

– of DPD

Sergeant Donna Ferrari

– of DPD

Detective Lionel Katz

– of DPD

Officer Rita Addison

– of DPD

Officer Mark Zevets

– of DPD

Dr Rob Weiss

– ballistics expert

Rosa Guzman

– forensic investigator

Ezekiel (Zeke) Goins

– elderly Melungeon

Samuel Goins

–

Zeke’s brother, a Detroit city councillor

Martha Bell

– urban regenerator, Zeke’s landlady

Keisha Bell

– Martha’s daughter

Grant T. Miller

– man Zeke Goins suspects killed his son, Elvis

Marta Sosobowski

– widow of deceased Detroit cop, John Sosobowski

Stefan and Richard Voss

– undertakers

Kyle Redmond

– an auto wrecker

1 December 1978 – Detroit, Michigan

His breath came in short, spiky gasps as his face was pushed hard into the unyielding brickwork in front of him. There was

a gun jammed against the side of his head. It was wielded by the same unknown person who had twisted his arm up his back so

that his hand nearly touched his head. He was afraid, but also angry. In spite of not being able to breathe properly, he yelled,

‘You fucking Purple motherfucker!’

But there was no reply, none of the usual murmurs of approval from the other gang members that generally accompanied hits

of this kind. Was there anyone else with whoever had grabbed him? He began to feel the blood drain from his face as he considered

the possibility that his assailant was alone. Apart from the shame he felt at being somehow disabled by possibly just one

person, he also knew what this could mean on another level. Every so often kids like him just got taken. Generally it was

by some sort of wacko freak who wanted to have sex with them – or with their body after they were dead. He’d seen that movie

The Hills Have Eyes

; he knew what went on.

‘Listen, man, I ain’t gonna let you have my butt!’ he said, and then instantly regretted it. His ma always said his mouth

was way too big for his head. The pressure on his arm and then from the gun against his temple increased. Either he’d hit

on the truth, or he’d just enraged his attacker still further. After all, if he wasn’t homosexual,

he had just insulted him. Then it got worse. ‘But if you gonna rob me, then that’s cool,’ he blurted. ‘Or . . . no, it ain’t cool,

but . . .’

But he didn’t want to be robbed either! Again, he panicked.

‘Not that I’m sayin’ you’re a faggot or nothing, man,’ he said. ‘Maybe you just want my stuff. I dunno!’ Then his voice rose

in terror and he yelled, ‘Just tell me what you do want, you crazy freak!’

There was snow on the ground underneath his feet. He looked down at it, knowing with a certainty that made his head dizzy

that his blood and brains were going to colour its city greyness red. He began to shiver. The gunman, his weapon pointed at

his head, pulled the muzzle back just ever so slightly. ‘Why are you going to kill me, man?’ the boy cried plaintively. ‘I

ain’t nothing special. What I ever do to you?’

But he never got an answer to that or any other question. His assailant pulled the trigger at just short of point-blank range,

and as the boy himself had imagined in the last moments of his life, his blood and brains turned the Detroit winter snow red.

27 November 2009 – İstanbul, Turkey

Inspector Çetin İkmen’s office was cold. The police station heating system had developed a fault, and so everyone was having

to make do with tiny, weak electric heaters. Also İkmen was not actually in his office, which always made it, so his sergeant

Ayşe Farsakoğlu believed, even more dreary and cheerless.

She leaned towards the tiny one-bar heater and thought about how badly her week without her boss was starting. So far, since

İkmen and another inspector, Mehmet Süleyman, had left to go to a policing conference abroad, first the computer system had

thrown a tantrum, and then the heating had broken down. It was almost as if the fabric of the building was protesting at their

absence. Ayşe herself always felt lost without İkmen, and whenever Süleyman was out of town, she worried. Some years before,

she’d had a brief affair with the handsome, urbane Mehmet. She still, in spite of his so far two marriages as well as numerous

affairs and liaisons, had feelings for him. Where the two officers had gone, representing the entire Turkish police force,

was a very long way away, to a place apparently even colder than İstanbul. As she leaned still further in towards the fire,

Ayşe found such an idea almost beyond belief. Then a knock at the door made her look up. ‘Come in.’

The door opened to reveal a slightly overweight dark man in his late forties.

‘Sergeant Melik.’

İzzet Melik was Mehmet Süleyman’s sergeant, and like Ayşe Farsakoğlu, he was not finding the absence of his boss or the bitterly

cold November wind easy to deal with. He was also, Ayşe noticed, carrying a paper bag that appeared to be steaming. He held

it up so that she could see it. ‘Börek,’ he said, announcing the presence of hot, savoury Turkish pastries. ‘If the heating’s

going to be down for a while, we need to eat properly and keep warm.’

Ayşe smiled. İzzet, in spite of his tough, macho-man exterior, was a kind and rather cultured soul who had held a romantic

torch for her, in silence, for years.

‘That’s a very nice thought,’ she said.

He took a tissue out of his pocket and then picked a triangular pastry out of the bag and wrapped it up for her. ‘Mind if

I join you, Sergeant Farsakoğlu?’

He was always so careful to be proper and respectful with her. As she looked at him, in spite of his heaviness and lack of

physical grace, Ayşe felt herself warm to him. Like her boss, Çetin İkmen, İzzet Melik was a ‘good’ man. What you saw was,

generally, what you got. No subterfuge, no hidden agendas, none of the fascinating mercurial scariness that could surface

in Mehmet Süleyman from time to time. She pointed to the battered chair behind İkmen’s desk and said, ‘Bring that over.’

He smiled. For a while they both sat in companionable silence, eating their börek, İzzet pulling his coat in tight around

his shoulders. Then Ayşe said, ‘So this conference our bosses have gone to . . .’

‘

Policing in Changing Urban Environments

,’ İzzet said, quoting the conference title verbatim.

‘What’s it . . .’

‘About?’ He shrugged. ‘I think it’s about gangs and drugs and migration and how those things, and other factors, affect life

in a modern city.’

Ayşe bit into a particularly cheesy bit of her börek and was amazed at just how much better it made her feel.

‘Officers are going from all over the world,’ İzzet continued. ‘But then changing urban environments affect us all. You know

this city. İstanbul, had only two million inhabitants back in 1978? We’re now twelve million, at least.’

‘More people, more problems,’ Ayşe said.

‘Yes. And a lot of those problems are global now too,’ he said. ‘Kids from New York to Bangkok sniff gas, shove cocaine up

their noses and make up rap tunes about inner-city alienation. The internet allows terrorist groups to reach out to men and

women on the streets of cities everywhere. Everything’s expanding, complicating, getting faster.’ He frowned. ‘If we don’t

either take control of it, try to understand it or both, we could find ourselves in the middle of an urban nightmare, a real

futuristic dystopia.’

İzzet was way cleverer than he looked. Sometimes he was too clever. Ayşe knew what a dystopia was, but she never would have

used the word herself. She finished her börek and then wiped her fingers on the tissue. ‘Well, whatever comes out of it,’

she said, ‘Inspector İkmen and Inspector Süleyman are getting to go to America. Çetin Bey was a little nervous, you know.

Such a long flight!’