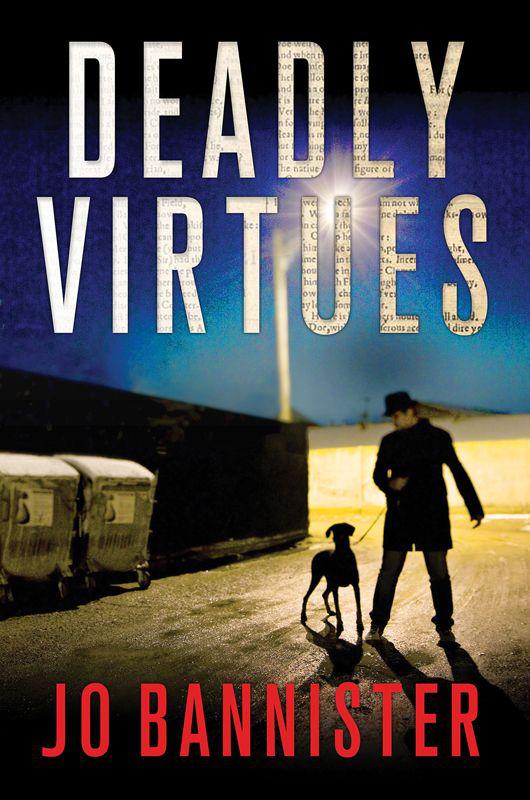

Deadly Virtues

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

J

EROME CARDY KNEW

he was going to die the moment he saw the other car in his rearview mirror. He knew it wasn’t going to stop: it was already too close, if it was braking at all it was too little too late, and he had nowhere left to go. As soon as the lights changed, a milk tanker the size of Rutland had moved into the junction. With enough milk to protect a generation from rickets in front and the big silver hatchback coming up fast behind, all Jerome could do was brace himself for the inevitable. He knew what was going to happen. He’d known for weeks.

He could have got out while there was still time. But he’d had too much to lose. He’d told himself that it might never happen. That the future isn’t set in stone. That if he was careful, if he kept out of trouble, no one could touch him. If he played it cool, stayed out of reach, he might never have to choose between the love of his life and, well, his life.…

And now it was too late to choose. The choice had been made for him. All Jerome could do was close his eyes, make himself small behind the wheel, and wait.

The impact, when it came, was less than he’d been expecting. Jerome’s car stayed where it was, held by its own handbrake; the milk tanker found the gap it had been waiting for and moved off; Jerome rocked for a moment in his seat belt, then settled back, still waiting.

When nothing else happened, cautiously he opened one eye.

It hadn’t been enough of an accident to stop the rush-hour traffic. The cars that had been in line behind him were now carefully edging past and on their way home. Not so much an accident as a shunt: if nobody’s hurt, you exchange details and you, too, get on your way. Jerome wasn’t hurt. He turned slowly in his seat to look behind him.

The other driver was a middle-aged woman, her mouth shocked to a dark round O. She made no move, nor did her expression change, as he slowly got out of his car and walked back to her. “Are you all right?”

She blinked, and went from total paralysis to frantic hyperactivity without passing through normal. She didn’t answer him but dived into the well of the passenger seat, scrabbling for her handbag. “We have to call the police! Have you got a phone? I have a phone—in here somewhere. I can’t find it! Have you got a phone? We have to call the police.”

“Well, actually,” said Jerome gently, “we don’t. Unless you’re hurt. I’m not hurt, and nobody else was involved. We can just exchange details and let the insurance sort it out.”

Her eyes stretched almost as wide as her mouth. She was a well-dressed, middle-aged, middle-class woman who might never have been in an accident before. The little card from her insurers that told her what to do in the event of an incident hadn’t warned her how distressed she’d be, how difficult she’d find it to act logically or even to make sense.

Jerome said again, “

Are

you hurt? Do we need an ambulance?”

After a moment she shook her head. “No. You?”

“I’m fine,” he assured her. “Listen, why don’t we park your car, I’ll drive you home, and we’ll swap details over a cup of tea?”

It was as if she was drowning and he’d thrown her a lifeline, but she didn’t like to grab it because she didn’t know where it had been. “Can we? Don’t we have to call the police?”

He shook his head. “It’s a minor traffic accident. Nobody’s hurt—nobody’s drunk—nobody’s committed an offense. We pass it over to the insurers. I’ll park your car if you don’t want to.” He opened her door and extended a courteous hand.

Her name was Evelyn Wiltshire. She was a middle-aged, middle-class Englishwoman, and she was also shocked, which may have been part of it, but mainly she just wasn’t used to young black men trying to take her by the hand. She recoiled instinctively. “Police! We need to call the police. I have a phone, somewhere.…”

Jerome fought to keep calm. If he snapped at her, if he frightened her, the opportunity to sort this out in a civilized fashion would be gone. And he had much more to lose than she did. “My name is Jerome. I’m a second-year law student. Really, I wouldn’t tell you this was all right if it wasn’t. Why would I? The accident wasn’t my fault. It’s not me the police will accuse of driving carelessly.”

Mrs. Wiltshire had finally found the phone. She stared at it as if it might bite. She stared at Jerome, ditto. His future hung by a thread.

She’d been brought up to do the right thing, even if it wasn’t in her own best interests. She started to dial.

Jerome felt himself grow desperate. “If you’re worried about the cost, why don’t we just fix our own dents? We don’t even have to involve the insurers, if you don’t want to. There really isn’t that much damage. Is that all right? Can we do that?”

“But … I ran into you.…”

“Yes. That’s okay. My father owns a garage—he’ll sort me out. There’s no need to involve the police. Is that all right?”

For a moment longer it hung in the balance. Then Mrs. Wiltshire swallowed. Fifty years of middle-class morality weighed more with her than her own immediate wishes. “No, I’m sorry. I’m going to call the police.”

Jerome was backing away before she’d finished dialing. “I’m sorry, too. I really am sorry. But I can’t wait.” He ran back to his car and drove off without knowing or even caring where he was driving to, only that he was putting distance between himself and the scene of the accident. Such a little accident. Such a trivial reason to die.

* * *

“I see you took my advice.” The woman had a nose meant for pince-nez: sharp as a blade, with a pair of diamond gray eyes above. Everything about her—the nose, the glasses, the tailored suit she wore, the way she scraped her dark hair away from her face and pinned it into a ruthless bun—said

severe.

But as she glanced at the dog curled up on her rug, she smiled, and the smile knocked ten years off her age and softened her face in unexpected ways. Her name was Laura Fry, and she was a trauma therapist.

The man looked at the dog, too. As if he couldn’t quite remember where it had come from. “Yes.”

“Is it helping?”

He considered. “I’m not sure.”

“It’s a nice dog. I’d have thought you’d enjoy the company.”

“I do.”

“Being alone can become a habit that’s hard to break.”

“Yes.”

Laura Fry smiled again. “Gabriel, this process would be more useful if you didn’t spend words as if they were fifty-pound notes.”

The man blinked, managed a pale flicker of a grin. “Sorry.” Then, as if he was trying to cooperate, to enter into the spirit of the thing: “I talk to the dog.”

“Good.” Laura nodded reassuringly. “Talking to the dog is good.”

A faint, fragile frown. “Is it?”

“Of course. She likes you talking to her, doesn’t she?”

“Yes.”

“And you feel better for talking to her?”

Again, he had to think. “I suppose so.”

“Then where’s the downside? Unless you start thinking she’s talking back.” He didn’t return her sly grin, so she pressed on. “Gabriel, this was always going to be hard. We both knew that. Getting a dog isn’t going to turn your life around—make you forget what happened, or make it hurt any less. It’s a dog, not a magician.

“But it will help. You need to find ways of relating to the world again, and looking after something that needs you is a start. It doesn’t actually matter whether you like dogs or not. She’s your responsibility now. She was a stray dog with nothing, not even much time left, until you came along. Now she has a home and someone to love. You don’t even have to love her in return. A square meal every day and she’ll

think

you love her, and that’s what counts.”

“Then what’s the point?” His brow was creased, as if he was genuinely trying to understand. He was a man in his late thirties with rather a lot of dark curly hair and creases that looked like laughter lines around his deep-set brown eyes. They’d been there a long time. He hadn’t laughed much recently.

Laura elevated a pencil-sharp eyebrow. “Apart from the fact that because of you she lives instead of dying? Looking after things is good for us. It makes us feel needed. It makes us think about something beyond our own hurts. It forces us into some kind of routine, and routine is good, too. You’re eating better, aren’t you? I can see. You make her meal, and then you get something for yourself. She needs walking, so you walk her—fresh air, exercise, nod an acknowledgment at other people doing the same thing. You were hardly leaving the house, and now you are. That’s the point.”

She looked down at the dog again, all nose and legs, curled on the rug as if posing for an illuminated manuscript. “What do you call her?”

“Patience.”

“Ah.” Just that.

Gabriel Ash looked at her warily. “That’s significant?”

“Possibly. Do you know why people talk to dogs?” He waited. “Because they feel silly talking to themselves. It isn’t always easy to find a human confidant. The dog is an uncritical listener”—the diamond gray eyes twinkled mischievously—“a bit like a therapist. Talking to a dog is like holding a conversation with yourself—with another aspect of yourself. The fact that you call your dog Patience suggests to me that, somewhere inside yourself, you recognize the fact that patience is what you need. To be gentle with yourself, to give yourself time to come to terms with what happened. You could have called her Spotty, or Snowball.”

He almost flinched as he looked down at the animal at his feet. “If I’d called her Snowball, she’d never have spoken to me again.”

“Ah.”

He darted a furtive sideways look, as if he’d let something slip, something that would cause him trouble. But then, he always looked as if he was afraid of causing trouble. “Again with the ‘ah’?”

“You think she wouldn’t like it because it’s an animal’s name?”

“Because it’s not a name at all—it’s a thing. Like a chair, or a tablecloth. If we want animals as companions, why would we name them after inanimate objects? It’s not … respectful. Giving them a proper name—a person’s name—makes you think of them as some

one

rather than some

thing.

Encourages you to treat them decently.”

He saw the way Laura Fry was looking at him and rocked back in his chair, his gaunt face catching the light from the window. “And now you think that because I chose a bitch and gave her a woman’s name, I’m thinking of her as a wife substitute.”

The therapist shook her head. “Not at all. Gabriel, there’s nothing wrong with you. There’s nothing wrong with how you’re feeling or what you’re doing. Something terrible happened in your life, and you’re struggling to deal with it, and anything that helps, even a little bit, is a good thing. Getting a dog is a good thing. Caring about her is a good thing.

“You’re not mad. You’re not even slightly unhinged. In the normal way of things you and I would never have met. All I’m trying to do, all these conversations are about, is to help you find a way of managing what happened without it destroying you. Whatever you call her, if the dog gets you out of your chair and makes you go into the kitchen, and then makes you walk as far as the park, she’s already had a positive influence.” She leaned down and patted the white dog.