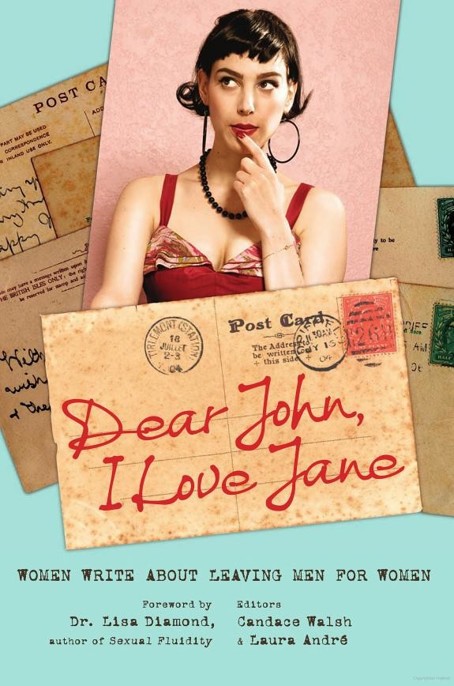

Dear John, I Love Jane: Women Write About Leaving Men for Women

Read Dear John, I Love Jane: Women Write About Leaving Men for Women Online

Authors: Laura Andre

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Gay & Lesbian, #Lgbt, #Family & Relationships, #General, #Divorce & Separation, #Interpersonal Relations, #Marriage, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #Psychology, #Human Sexuality, #Self-Help, #Sexual Instruction, #Social Science, #Women's Studies, #Essays

Table of Contents

Inappropriate Things

’Til Death Do Us Part

So This Is Marriage . . .

The Search for Answers

Confronting Reality . . . Finally

Awakenings: Navigating the Spaces between In and Out

Walking a Tightrope in High Heels

Credit in the Un-Straight World

April 27, 1984

If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.

—Audre Lorde

Foreword

Dr. Lisa M. Diamond

T

his gripping collection of first-person narratives will undoubtedly expand and deepen your understanding of women’s sexuality, whether you are gay, straight, or somewhere in between. As someone who has been studying women’s erotic and affectional changes and transformations for over fifteen years, I am jumping for joy to see such stories on printed pages. Journeys such as these usually remain untold, unexplored, and uninvestigated, drowned out by the more familiar and predictable coming out stories that recount continuous, early-appearing, and readily identifiable same-sex attractions. The women in this volume have followed notably different—and remarkably diverse—routes to same-sex love and desire. Their single point of commonality is their compelling defiance of societal expectations about how women are “supposed” to discover, experience, interpret, and act on same-sex desires. Instead of tortured childhoods, these women report sudden and surprising adult experiences of same-sex desire—sometimes after ten, twenty, or thirty years of heterosexuality—which turn their worlds upside down. Listening to these women recount the perplexing bliss of their first same-sex affairs, coupled with the doubt, disapproval, and disrespect they suffered at the hands of friends and family, offers an utterly new perspective on women’s erotic lives.

There are statements in these stories that bowled me over because they so strongly resemble statements I’ve heard from the lesbian, bisexual, questioning, and heterosexual women I’ve been interviewing over the past fifteen years.

• I wish I had realized earlier that I didn’t want to be like those girls so much as I just wanted them.

• I’m not attracted to women . . . but I’m falling in love with this person.

• I knew I had shifted from being a “straight” girl. Where along the continuum I landed, I wasn’t sure yet.

• Inside, a part of me still wavered about whether my changing sexuality was sparked because of who she was, as my friend, or because she is a woman.

• I’ve always felt like I was somewhat of a fraud in the gay community. Where was my gay history?

• In three short months, I had gone from A (a hopelessly straight girl) to Z (hopelessly in love with a woman).

Quite simply, voices and experiences like these have been missing from our popular

and

scientific understandings of female sexuality, and the twists and turns that sexuality takes over the life course. Instead, when women make unexpected mid-life transitions to same-sex love and desire, when they fall madly in love with “just this one woman,” they find themselves discounted and dismissed as inauthentic by the larger gay community because they have no long childhood struggles with nascent same-sex desires to report, no adolescent self-hatred. Some of them—glory be—enjoyed or continue to enjoy relationships with husbands and boyfriends. What’s

that

about?

The truth is that these journeys are far more common than most people think, and they deserve our full attention. These women’s candor is refreshing, revelatory, and deeply important to our attempts to understand and validate same-sex love and desire in all its miraculous forms. These women have bravely explored every edge of the supposed boundary dividing queer from straight, before from after, truth from falsehood, self from façade, and girl from woman. They have shown that the closer one gets to the boundary, the more ephemeral it appears to be, shifting and mutating like a smoke ring before our very eyes. In the end, each of these women makes her own peace with identity, desire, kinship, community, partnership, and self, sometimes with a lover by her side, sometimes alone. Each journey has its own logic and truth, its own “deep structure” imprinted in memory, desire, sweat, salt, and the powerful bond between two women who cannot resist one another, despite the horrified shock of everyone around them.

The past looms large in these narratives. As one woman’s ex-boyfriend says, matter-of-factly, “History is important.” History

is

important, but where is it to be found? Which past matters? Which experiences should we rely upon as signposts for the future? These women steadfastly resist the impetus to erase or discount past identities, desires, relationships, but instead choose the harder role of integration, moving toward a future that can contain contradiction, fluidity, change, and dynamism. As one woman boldly claims, “You won’t find me re-writing history to say that I was gay all along. I was straight. Now I am gay. I won’t insult my past self by saying I was in denial or confused.” It takes guts to hold this line and to speak one’s truth to a society that doesn’t understand it.

To be clear, men are not villains here. In contrast to the classic stereotype of men as uniformly blocking their wives’ and girlfriends’ processes of sexual questioning, we meet a notably different cast of male characters in these women’s stories. There are men tortured by the loss of women who couldn’t fully love them back; men who give their lovers lessons in their own bodies, lessons that will eventually lead these women into the arms of other women. As one husband told his wife as she wrestled with blossoming same-sex desires, “Sometimes when you encourage people to be all they can be, you get a little more than you bargained for.” Some of the men in these narratives resist and denounce; others relinquish and mourn, affirm and accept. Watching women as they struggle to reconcile the past, current, and future roles of these complex men in their lives is one of the most fascinating and original gifts of this collection.

No matter what your own history, this book will challenge and expand your notion of what it means to be (for lack of a better, broader term) queer: Queer women come out at fifteen, at eighteen, at forty, and at sixty. Queer women live openly and in secret. Queer women get and stay married to (open-minded) men. Queer women settle down with the first woman they ever kissed. Queer women have children with men, with women, with both. Queer women play the field. Queer women make lifelong commitments. Queer women keep questioning. Queer women strike out into new and unfamiliar territory. As one woman says, “You never know where love and honesty will take you.” This book is a series of unique journeys through love and honesty (with plenty of lust, sweat, fumbling, and ecstasy thrown in) that has much to teach us about the nature of female affection and eroticism. We owe all of the participants a debt of gratitude for their candor, and for allowing us to listen and learn.

Introduction

Candace Walsh and Laura André

W

hen we met each other two years ago (on

Match.com

), we immediately noticed a shared love of language and books. And almost since that time, we’ve been working on books together. As is often the case with new lovers, our early conversations touched upon our respective romantic histories. Candace had recently left her husband of seven years and was dating women for the first time. Laura, who had never dated men (well, there was that guy from band in tenth grade), had also never dated a woman who had Candace’s heterosexual bona fides (traditional wedding, children from that marriage). We had lots to discuss and learn. We had been living on two different planets and were about to touch down on a third.

It was a particular kind of conversation. Not two women sharing our long lists of ex-girlfriends, or a woman talking to a man about her divorce—it was a conversation that more and more women are having on private and public levels. Cynthia Nixon, Wanda Sykes, Meredith Baxter, Carol Leifer, and countless others have left the fold of heterosexual identity to enter into or pursue same-sex relationships. It used to be the punch line of a joke if a man’s last girlfriend or wife left him and went on to partner with a woman. Now it is just something that happens—something that doesn’t cast either party as a villain or a laughingstock. The instance of a woman leaving a man for a woman has more visibility and is becoming less of a shocker (although it remains a curiosity because it challenges so many commonly held truisms about what women want).

It’s a relationship that reflects circumstances our society is now absorbing more frequently. As Dr. Lisa Diamond’s recent ground-breaking book,

Sexual Fluidity,

makes clear, women’s sexual desire and identity are not only capable of shifting, they do shift. Instead of standing on the outside looking in, this book is made up of intimate perspectives shared from inside women’s lives. Diamond’s research has given us a new language to talk about our capacity to love. The women in this book are writing from a deeper understanding of their emotional and sexual territory.

Love is seen as a soft, romantic thing, but it can also be as leveling as an earthquake. It can rework and redefine people’s lives in ways they never imagined. It’s the reason why people move halfway around the world, get married, and expose themselves to rejection and ridicule—or delight. It can make us act like fools, or make us wise with the knowledge of what’s important and what is superfluous. This book is a series of love stories, bursting with all of the passion, uncertainty, self-discovery, and sacrifice that make up the truly good ones.

CANDACE:

There were a series of physical steps that led me out of my marriage: loading my station wagon with “what would you grab in a slow-burning fire” items (journals, clothing, children’s books, sippy cups, a tin of smoked paprika, and all of my Joan Didion books); signing the three-month lease on my rented casita; buying groceries that were put away in a new refrigerator and cabinets. Key among these steps was my Internet search for books on women leaving men for women. Women who “jumped the fence,” “went gay,” “were lesbians all along,” or “betrayed their vows.” What I was doing felt radical in the contexts of both the straight community I was leaving behind and the lesbian community that seemed like a distant shore on the horizon. The ground under my feet was a no-man’s-land between two territories. Would they be hostile? Friendly? Guarded? A mix?

LAURA:

You have the double whammy of processing your divorce and coming to terms with your sexuality. It gives new meaning to the term “disorienting.”

CANDACE:

I wanted to get my bearings—to read stories by women who had gone down the same path I was walking with my fingers crossed. I ordered

And Then I Met This Woman

and

From Wedded Wife to Lesbian Life

, which were well-done and gave me hope, but were also rooted in a different time. Many of the contributors came out in the ’70s and ’80s, when society was a lot less accepting. Mothers often ran the risk of losing their kids in divorce court if their sexuality came up. (Not that we’re completely out of the woods—recently, a friend told me about her new relationship, and then told me to keep it in confidence, since her girlfriend was going through a custody battle.)

A number of the women in this book had to confront the drama of telling their parents about the shift in their sexuality. Parents do still disown their kids or become estranged from them due to their sexuality, but it’s becoming more rare to encounter that level of judgment. Categorically disapproving of gay people is becoming more and more universally tacky, right up there with walking around Wal-Mart dressed in a muscle shirt and bike shorts.

LAURA:

While some of the writers found a sense of community online and in books, others felt terribly alone as they struggled to deal with the changes they were going through. And even those who found community online still had to live their offline life at a certain level of isolation.

CANDACE:

I wanted to be in a room surrounded by women who were now on the other side, and had stories to tell. A support group, or a retreat, that involved a tall stacked-stone fireplace, and tumblers of shiraz. A klatch of smart, sparkling women like the ones who gathered at Meryl Streep’s character’s house in

It’s Complicated

. I wanted to dish.

What was your first time like? What did your mother say? How long did you wait to tell her? Does she even know? Did you lose any female friends who were afraid you were going to start vibing them (oh, please)? Are you now in a relationship with one of your female friends? Are long-time lesbians not taking you seriously? Isn’t it weird that men try to pick you and your girlfriend up when you go out to restaurants?

LAURA:

That last bit actually happened to us.

CANDACE:

It was another round of adolescence. How to flirt. How to date. Sexual experience: zero. Everything old is new again. I was on a different planet where everything seemed mostly the same, except that little differences tipped me off to the fact that I couldn’t go home again. I had to craft a new home out of pieces of my old life and my new one.

As the editor of

Ask Me About My Divorce: Women Open Up About Moving On

(Seal Press, 2009)

,

I knew full well that if I couldn’t find the book I wanted to read, I could take a stab at creating it. Every editor wonders whether her anthology idea is a quirk or a bellwether, especially if it comes from a personal place. Laura had generously joined me in the trenches of pulling together

Ask Me About My Divorce

and I knew I didn’t want to edit another book without her.

LAURA:

I was really happy—and relieved—when the submissions started rolling in. I wasn’t sure that there would be that many women out there who were willing to sit down and write essays detailing their experiences. After all, we’re talking about major life changes here, and it’s not always easy to write well about them. But as soon as I started reading the essays, I forgot about the quantity and began getting lost in the individual stories that were being told. Real lives, unfolding and caroming and being recorded right here, as potential elements of our book. I began to see how it was falling into place, and it was powerful.

CANDACE:

I thought there’d be enough submissions. Not a deluge, but

enough.

And that if they were not top-notch in the writing department but story-driven, I could work them up. Well, we got a deluge (130), and we had more than enough to choose from; we selected the ones that were the most powerfully written. But I have to say, Laura’s anxiety fueled her posting of the call for submissions all over the Internet. She spent days. And it paid off.

Before we submitted the book proposal, we sat together and watched the March 2009

Oprah

episode on women leaving men for other women. Guests included Dr. Lisa Diamond, who patiently explained women’s sexual fluidity to the puzzled host and a millions-strong televised audience, and Micki Grimland, raised Baptist and married for twenty-four years to her husband, mom of three, declaiming her personal truth: she left that husband (still a dear friend), because she realized that she was a lesbian. Little did we know that Diamond and Grimland would accede so happily and graciously to contribute to our project. It wasn’t just my story. It was a conflation of timing, a bouquet of high-profile women’s decisions at a particular point of same-sex relationship acceptance, and a deeper understanding of women’s fluid sexuality, which historically had been woefully under-researched.

LAURA:

Coming from an academic background, I can say that we’re seeing the fruition of what seemed solely theoretical twenty years ago. The idea that sexuality can be pegged to simple binaries (straight/gay, men/ women), and that those binary pairs are absolute, has been completely dissolved by the notion of sexual fluidity. The essayists in this book are living proof that sexuality can change over time, often against our will. The women in this book didn’t set out to dismantle their marriages and relationships; the last thing they wanted was to hurt their husbands or boyfriends. This switching doesn’t happen voluntarily, which will frustrate those who believe that sexual orientation is a choice, like ordering from a catalog. The cultural lesbianism that some have adopted is separate from this core thing that happened to these writers: falling in love with a woman. Theory aside, what it comes down to is actual lived experience, and through these personal essays, we have first-person accounts—primary source material—not of queer theory, but of queerness itself.

CANDACE:

These are not love stories with templates that are delivered to girls from Walt Disney, these are not women who found their princes. We are told, in this book, that we can keep our whole selves

and

still find love. Or it finds us. We are awakened with a kiss, a look, a job interview, or a “non-date.” Something in our destinies rips us out of what’s comfortable, expected, and rubber-stamped. We are given a choice. Will we follow bliss? Or hunker down and live a conciliatory lie?

I was hungry for a story that didn’t make me suspect, or a liar, that didn’t cast a third of my life into the “mistake” or “do-over” category. I found my tribe. Like many of the women in this book, I hold my children close, close enough to model an example of authenticity while also feeling moments of uncertainty and even anxiety (isn’t that an indication that I’m not sleepwalking through life?). My children love my partner ardently. I have expanded their definition of what love looks like. Recently, my five-year-old son saw my Valentine’s Day present for Laura, wrapped in pink tissue paper. “Who’s that for?” he asked. “That’s for Laura,” I said. “Oh, good,” he replied.

LAURA:

Recently Candace told me that she was glad I never doubted her. The truth is, I didn’t ever question her commitment to finding a woman to fulfill her, regardless of the fact that she once identified as straight. I knew what she gave up. One doesn’t walk away from full-blown heterosexual privilege on a whim. It surprised me how many of the essays in the book refer to people who were suspicious that a woman who once loved a man could never love a woman as fully. That she must be experimenting, playing around, not serious.

The whole idea that women leaving men for women is some sort of a trendy, hot thing to do is patronizing and dismissive. This book is not about BFFs frenching in bars to turn on their boyfriends. Especially in today’s climate, which is still—despite much progress—patently homophobic.

CANDACE:

And downright punishing, when you know what you’re missing. The women in this book once benefited from heterosexual privilege. We had the married income tax status, the pensions waiting for us, the right to be at our beloved’s bedside in the hospital. The frosty-white wedding albums filled with unequivocally supportive friends and relatives. We walked away.

LAURA:

As Jennifer Baumgardner notes in the epilogue to this book, women taking charge of their sexual identity is a specifically feminist gesture, one that is sure to ruffle a few conservatives’ feathers. But the truly immoral thing is to deny one’s real identity, whether it has been simmering for years or it’s newly sprung. I admire the women in this book so much, as they’re really brave to have done what they’ve done, and then write about it so honestly.

One of the funny things about dating Candace is how, at the beginning, she was more out than I was in public. I’ve always been a lesbian, but I was used to being very low-key in public. And here she comes along, fresh from the hetero fold, wanting to hold hands, call me “honey,” and give me little kisses in public, and I stiffened up, which I feel bad about. I think those experiences opened both of our eyes to how heterosexual privilege operates in terms of public displays of affection. Many of the writers in the book express dismay that they don’t feel comfortable holding hands with their female partners in public—that simple, spontaneous gestures like that are something they miss from their previous relationships with men.

CANDACE:

Women who come out in their thirties or forties have a lot in common with high school girls coming out today into an environment that’s comparatively accepting. They may have a lack of self-consciousness about holding hands or being affectionate in public, which reveals evidence about the nature of their relationship.

I noticed the awareness of a growing reflexive restraint, and felt it to be a damming up, a hemming in, of the flow of my romantic impulses. I am not a neuroscientist, but that can’t be preferable to the kind of freedom and safety heterosexual couples take for granted.

LAURA:

Another thing that was a big shocker for me was getting used to the kids. I thought I had chosen a life without children, and I was content with that. Falling in love with Candace not only meant having to confront my fear of children; it also meant letting go of my life as I thought it would look like. So, while I never left a man for a woman, I did have to switch my identity to someone who finds herself at children’s music recitals and ice skating lessons, and that made me more empathetic to the

“Oh my God, I can’t believe this is my life”

emotion that so many of our writers express.