Dear Mr. Henshaw (5 page)

Authors: Beverly Cleary

Monday, February 5

Dear Mr. Henshaw,

I don't have to pretend to write to Mr. Henshaw anymore. I have learned to say what I think on a piece of paper. And I don't hate my father either. I can't hate him. Maybe things would be easier if I could.

Yesterday after I hung up on Dad I flopped down on my bed and cried and swore and pounded my pillow. I felt so terrible about Bandit riding around with a strange trucker and Dad taking another boy out for pizza when I was all alone in the house with the mildewed bathroom when it was raining outside and I was hungry. The worst part of all was I knew if Dad took someone to a pizza place for dinner, he wouldn't have phoned me at all, no matter what he said. He would have too much fun playing video games.

Then I heard Mom's car stop out in front. I hurried and washed my face and tried to look as if I hadn't been crying, but I couldn't fool Mom. She came to the door of my room and

said, “Hi, Leigh.” I tried to look away, but she came closer in the dim light and said, “What's the matter, Leigh?”

“Nothing,” I said, but she knew better. She sat down and put her arm around me.

I tried hard not to cry, but I couldn't help it. “Dad lost Bandit,” I finally managed to say.

“Oh, Leigh,” she said, and I blubbered out the whole story, pizza and all.

We just sat there awhile, and then I said, “Why did you have to go and marry him?”

“Because I was in love with him,” she said.

“Why did you stop?” I asked.

“We just got married too young,” she said. “Growing up in that little valley town with nothing but sagebrush, oil wells and jackrabbits there wasn't much to do. I remember at night how I used to look out at the lights of Bakersfield in the distance and wish I could live in a place like that, it looked so big and exciting. It seems funny now, but then it seemed like New York or Paris.

“After high school the boys mostly went to work in the oil fields or joined the army, and the girls got married. Some people went to college, but I couldn't get my parents interested in helping me. After graduation your Dad came along in a big truck andâwell, that was that. He was big and handsome and nothing seemed to bother him, and the way he handled his rigâwell, he seemed like a knight in shining armor. Things weren't too happy at home with your grandfather drinking and all, so your Dad and I ran off to Las Vegas and got married. I enjoyed riding with him until you came along, andâwell, by that time I had had enough of highways and truck stops. I stayed home with you, and he was gone most of the time.”

I felt a little better when Mom said she was tired of life on the road. Maybe I wasn't to blame after all. I remembered, too, how Mom and I were alone a lot and how I hated living in that mobile home. About the only places we

ever went were the laundromat and the library. Mom read a lot and she used to read to me, too. She used to talk a lot about her elementary school principal, who was so excited about reading she had the whole school celebrate books and authors every April.

Now Mom went on. “I didn't think playing pinball machines in a tavern on Saturday night was fun anymore. Maybe I grew up and your father didn't.”

Suddenly Mom began to cry. I felt terrible making Mom cry, so I began to cry some more, and we both cried until she said, “It's not your fault, Leigh. You mustn't ever think that. Your Dad has many good qualities. We just married too young, and he loves the excitement of life on the road, and I don't.”

“But he lost Bandit,” I said. “He didn't leave the cab door open for him when it was snowing.”

“Maybe Bandit is just a bum,” said Mom. “Some dogs are, you know. Remember how he jumped into your father's cab in the first place?

Maybe he was ready to move on to another truck.”

She could be right, but I didn't like to think so. I was almost afraid to ask the next question, but I did. “Mom, do you still love Dad?”

“Please don't ask me,” she said. I didn't know what to do, so I just sat there until she wiped her eyes and blew her nose and said, “Come on, Leigh, let's go out.”

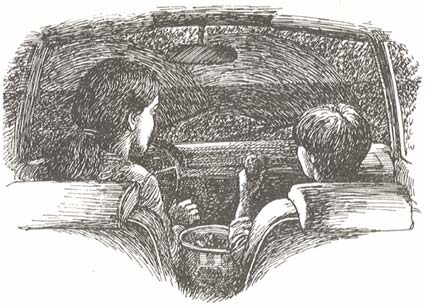

So we got in the car and drove to that fried chicken place and picked up a bucket of fried chicken. Then we drove down by the ocean and ate the chicken with rain sliding down the windshield and waves breaking on the rocks.

There were little cartons of mashed potatoes and gravy in the bucket of chicken, but someone had forgotten the plastic forks. We scooped up the potato with chicken bones, which made us laugh a little. Mom turned on the windshield wipers and out in the dark we could see the white of the breakers. We opened the windows so we could hear them roll in and break, one after another.

“You know,” said Mom, “whenever I watch the waves, I always feel that no matter how bad things seem, life will still go on.” That was how I felt, too, only I wouldn't have known how to say it, so I just said, “yeah.” Then we drove home.

I feel a whole lot better about Mom. I'm not so sure about Dad even though, as she says, he has good qualities. I don't like to think that Bandit is a bum, but maybe Mom is right.

Tuesday, February 6

Today I felt so tired I didn't have to try to walk slow on the way to school. I just naturally did. Mr. Fridley had already raised the flags when I got there. The California bear was right side up so maybe Mr. Fridley didn't need me to help him after all. I just threw my lunch down on the floor and didn't care if anybody stole any of it. By lunchtime I was hungry again, and when I found my little cheesecake missing, I was mad all over again.

I'm going to get whoever steals from my lunch. Then he'll be sorry. I'll really fix him. Or maybe it's a her. Either way, I'll get even.

I tried to start a story for Young Writers. I got as far as the title which was

Ways to Catch a Lunchbag Thief

. A mousetrap in the bag was all I could think of, and anyway my title sounded too much like Mr. Henshaw's book.

Today during spelling I got so mad thinking about the lunchbag thief that I asked to be excused to go to the bathroom. As I went out into

the hall, I scooped up the lunchbag closest to the door. I was about to drop-kick it down the hall when I felt a hand on my shoulder, and there was Mr. Fridley.

“What do you think you're doing?” he asked, and this time he wasn't being funny at all.

“Go ahead and tell the principal,” I said. “See if I care.”

“Maybe you don't,” he said, “but I do.”

That surprised me.

Then Mr. Fridley said, “I don't want to see a boy like you get into trouble, and that's where you're headed.”

“I don't have any friends in this rotten school.” I don't know why I said that. I guess I felt I had to say something.

“Who wants to be friends with someone who scowls all the time?” asked Mr. Fridley. “So you've got problems. Well, so has everyone else, if you take the trouble to notice.”

I thought of Dad up in the mountains chain

ing up eight heavy wheels in the snow, and I thought of Mom squirting deviled crab into hundreds of little cream puff shells and making billions of tiny sandwiches for golfers to gulp and wondering if Catering by Katy would be able to pay her enough to make the rent.

“Turning into a mean-eyed lunch-kicker won't help anything,” said Mr. Fridley. “You gotta think positively.”

“How?” I asked.

“That's for you to figure out,” he said and gave me a little shove toward my classroom.

Nobody noticed me put the lunchbag back on the floor.

Wednesday, February 7

Today after school I felt so rotten I decided to go for a walk. I wasn't going any special place, just walking. I had started down the street past the paint store and antique shops and bakery and all those places and on past the post office when I came to a sign that said

BUTTER

FLY TREES

. I had heard a lot about those trees where monarch butterflies fly thousands of miles to spend the winter. I followed arrows until I came to a grove of mossy pine and eucalyptus trees with signs saying

QUIET

. There was a big sign that said

WARNING

. $500

FINE FOR MOLESTING BUTTERFLIES IN ANY WAY

. I had to smile. Who would want to molest a butterfly?

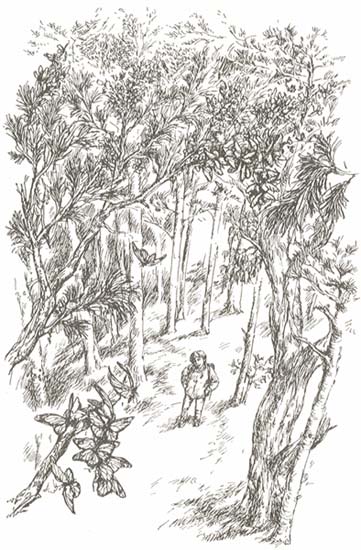

The place was so quiet, almost like church, that I tiptoed. The grove was shady, and at first I thought all the signs about butterflies must be for some kind of ripoff for tourists, because I saw only three or four monarchs flitting around. Then I discovered some of the branches looked strange, as if they were covered with little brown sticks.

Then the sun came out from behind a cloud. The sticks began to move, and slowly they opened wings and turned into orange and black butterflies, thousands of them quivering on one tree. Then they began to float off through the trees in the sunshine. Those clouds

of butterflies were so beautiful I felt good all over and just stood there watching them until the fog began to roll in, and the butterflies came back and turned into brown sticks again. They made me think of a story Mom used to read me about Cinderella returning from the ball.

I felt so good I ran all the way home, and while I was running I had an idea for my story.

I also noticed that some of the shops had metal boxes that said “Alarm System” up near their roof. So does the gas station next door. I wonder what is in those boxes.

Thursday, February 8

Today when I came home from school, I leaned over the fence and yelled at a man who works in the gas station, “Hey, Chuck, what's in that box that says Alarm System on the side of the station?” I know his name is Chuck because it says so on his uniform.

“Batteries,” Chuck told me. “Batteries and a bell.”

Batteries are something to think about.

I started another story which I hope will get printed in the Young Writers' Yearbook. I think I will call it

The Ten-Foot Wax Man

. All the boys in my class are writing weird stories full of monsters, lasers and creatures from outer space. Girls seem to be writing mostly poems or stories about horses.

In the middle of working on my story I had a bright idea. If I took my lunch in a black lunchbox, the kind men carry, and got some batteries, maybe I really could rig up a burglar alarm.

Friday, February 9

Today I got a letter from Dad postmarked Albuquerque, New Mexico. At least I thought it was a letter, but when I tore it open, I found a twenty-dollar bill and a paper napkin. He had written on the napkin, “Sorry about Bandit. Here's $20. Go buy yourself an ice cream cone. Dad.”

I was so mad I couldn't say anything. Mom read the napkin and said, “Your father doesn't mean you should actually buy an ice cream cone.”

“Then why did he write it?” I asked.

“That's his way of trying to say he really is sorry about Bandit. He's just not very good at expressing feelings.” Mom looked sad and said, “Some men aren't, you know.”

“What am I supposed to do with the twenty dollars?” I asked, not that we couldn't use it.

“Keep it,” said Mom. “It's yours, and it will come in handy.”

When I asked if I had to write and thank

Dad, Mom gave me a funny look and said, “That's up to you.”

Tonight I worked hard on my story for Young Writers about the ten-foot wax man and decided to save the twenty dollars toward a typewriter. When I get to be a real author I will need a typewriter.