Death and Taxes (29 page)

Pereira swept her flashlight from front to back. Boards, boxes, nothing big enough to hide behind and no one hiding. “Damn,” she said. “Not here.”

“No, wait.” I pictured the “cop,” dressed in his tans, his workbelt hanging like our equipment belts. I moved around to the back and motioned Pereira to the garage. She shone her light in. No car. No one.

Then I spotted it. The accoutrement of a big building job. The only other place to hide. Pereira saw it too—the idea must have come to us at the same moment. We moved almost silently to the Porta Potty. I could picture, inside, tan-clad legs braced against the edge, arms holding the door shut.

Pereira and I moved around back, caught the corners, and tipped it forward on its door.

I

PULLED OPEN THE

door of the Porta Potty. Ethan Simonov was slumped against one side. He was clutching a knife, about to drag it across his throat.

I stared at him in that tiny dank room, precursor to other closed cells for years to come. I froze, desperately wanting to leave him his way out. So much less painful—one slice of the carotid—than bleeding out your life drop by drop, day by day, hour by endless hour, in jail. Then I braced my foot and yanked the knife out of his hands.

Pereira was already calling the dispatcher for an ambulance.

We lifted Simonov out onto the lawn and sat him against an upright of the foundation. The pipe behind it was a good place to attach the handcuffs. Simonov’s cut was bleeding but not spurting. He’d live. I read him his rights.

He glared up at me, his dark ponytail now pulled free from his tan collar. “I’ve done time. I know what it’s like inside. I’m not going back to jail.”

“You killed Drem to keep from going back to jail?” I asked.

“I’ve got a record. Tax bastards got me once for not reporting. Drem would have made a sideshow of me this time: ‘Swap king does it again!’ There’s nothing those bastards hate more than taxpayers not reporting income at all.

I

didn’t get any income from the swaps, but the bastards would get me for taxes on the cost of services received, services I received, and conspiracy to keep everybody else’s from being taxed.”

You knew all that, and still you couldn’t give up being the swap king, I thought. Just like Howard, who would quit the force before he’d stop masterminding stings. And Mason Moon couldn’t give up the notoriety of the plop artist (or for that matter even his tacky T-shirt). Losing the business that was her whole identity undid Scookie Hogan.

And me—I wondered what it was that I couldn’t part with. Maybe open doors, long straight highways, my options always open. Knowing what had filled me with the need to escape hadn’t eradicated the urge to get on the freeway, turn up the stereo till it hurt my ears, and keep driving. But when I had to take an off ramp, I couldn’t imagine it leading anywhere but Berkeley, bringing me home to the other 120,000 people who were drinking

lattes

, looking nervously over their shoulders, and fighting for their open doors.

The wind flapped Simonov’s tan jacket. It rattled the plastic sheets over the lumber. “Give me back the knife,” he pleaded.

“Why didn’t you just pay the taxes, Ethan?”

His eyes scrunched, and he looked at me in disbelief. I remembered him the first time I saw him, standing behind the counter like a bazaar trader. For him, giving up the contest would be giving up entirely. “IRS’d never have bothered with me. I was too small potatoes. The swap club was all informal, nothing written. No way for them to find out. They’d never have looked at me at all if it hadn’t been for Lyn’s audit. And even then—if it had been anyone but Drem.” He shook his head. “There were no records. Nothing. I made sure of that. And then Drem found that damned sink, and the workman, and … He was a bulldog. He’d have hung on till he got me. Then it wouldn’t be county time; it’d be federal prison. I know what that’s like. I can’t be locked up!”

I thought of Tori Iversen, locked in twice as tight now. But what I said was “You killed a man.”

“He deserved to die. Guy was a bastard. Institutionalized reneger. Damn IRS gives you rules, then they don’t follow them themselves. Tell you one thing on the phone—if they’re wrong, they don’t stand behind it. Renegers. Can’t trust ’em on a deal. You do your part, you’re honest, they screw you. Drem, he was all of that. Then he even reneged on them, the IRS!”

I could hear sirens in the distance—not for Simonov, too soon. I felt numb, as I always do when a perp gives his rationalization for ending another person’s life. But for the swap king nothing was worse than reneging. And yet when he looked up again and pleaded, “Give me back the knife,” I was as tempted as I’d ever been.

I was still thinking about imprisonment—Simonov’s, Tori’s, the prison of a life Drem had made for himself, and Howard’s house—hours later, after Simonov had been taken to the hospital, after he’d called his lawyer and stopped talking.

When I got home, the living room was dark but for a fire—a big bustling, crackling red-and-yellow fire—in the hearth that had never hosted more than embers. The room smelled not of wood shavings but burning pine. And on the stereo Kris Kristofferson was singing “Me and Bobby McGee.” As my eyes adjusted to the dark, I could make out Howard sprawled on the couch, his legs flung over the back like an afghan. In the shadowy light his face looked gaunt, and his red curls were gray. As if the curtains of the future had parted.

I’d never really considered whether he’d be there twenty years from now. I’d never thought that far at all.

He swung his legs down and sat up. “So, Jill, is everything set with Simonov?”

I nodded, glancing under the coffee table till I found an open beer can. I took a long drink. It was still cold.

“Plenty more in the fridge.” Howard grinned. “It’s nice to have them all gone.” The tenants, he meant.

Settling down next to him, I said, “This is great. It’s like a different place. Smells like Yosemite.” But still I felt a tug of panic as I spoke. Windows may open, but you can’t always get out.

“The house has always had potential.”

“I never saw it.”

Howard laughed. “Well, Jill, it’s very, very difficult to truly understand something that you think you’ll never experience.”

“Touché.” I smiled.

Before I could speak, he said, “You know how pissed I was that you’d gotten me with the azalea. A whole lot more pissed than I’d been about Damon Hentry slipping through my fingers. I guess that was no secret, huh?” His voice was rough, unsure, as if he were speaking from a level he wasn’t used to treading. “I couldn’t believe you’d done that. I felt so, well, betrayed.” He was staring at the fire, away from me. He laughed uncomfortably. “I asked Connie, made it real awkward for her. I could tell she’d have done my taxes, meal deductions and all, for the rest of my life before she’d get in the middle of this.”

I felt my shoulders tighten. I felt a bit betrayed myself.

I

hadn’t talked to Pereira about any of this. But then, this relationship stuff was more virgin territory for a guy like Howard. And I owed him one. I put a hand on his arm. “I wondered what you and Connie were so edgy about. I thought she was going to kill you over your taxes.”

“No. That’s all worked out.”

The road forked here: Easy Unemotional Tax Discussion or Quicksand of Emotion. I leapt at the former. “You got all the restaurant food figures already?”

“No.”

“You gave up?”

“No.” He sounded at once sheepish and smug. “I filed for an extension. Then I cut a deal with Pereira. I never mention our problems again, and she’ll do my tax return.”

I laughed. “God, you must have really been a pain.”

He took my hand in both of his, but he didn’t look at me, and he didn’t laugh. “I operate in a world of stings, counterstings, drug dealers, lies, double crosses. You know how it is in Vice. Or maybe you don’t, quite. Maybe, like me, you don’t really know what life’s like for someone else. Nothing’s real. Other than the guys in Detail, there’s nothing you can count on, no one to trust, no firm ground at all.” He squeezed my hand hard.

I pressed my teeth together against the pain.

He didn’t look at me, but the intensity of that avoidance was greater than any gaze. “I count on the reality of what we have. And on my house.” His voice was trembling.

Mine was too, as I said, “I don’t want to be without you. But I need my doors open. When your arms are around me, I need to know they’re there for love, not protection, not squeezing me in.”

He did the last thing I expected. He laughed. “Okay, okay. Just promise me you’ll never tell anyone in Berkeley you even thought I was”—he swallowed and forced out the word—“conservative.”

I leaned against his chest and felt the warmth of his body. I hadn’t had a vision of how this issue would resolve. But if I’d thought of it, I would have hoped that Howard would understand about freedom and still we’d return to the comfortable status quo. It hadn’t occurred to me that it would kick us to a different level, one that would leave us more exposed. We’d had that easy relationship so long. It had seemed it was attuned to Howard’s temperament.

Maybe. Or maybe it had been more in line with my own than I’d realized.

Now I felt disoriented, like when you’re hurrying downstairs and you miscount steps and there’s one more than you expected. You step off, and for an instant you’re in nothingness, and you don’t know how you’ll land, or even if you’ll be able to keep your balance.

Susan Dunlap (b. 1943) is the author of more than twenty mystery novels and a founding member of Sisters in Crime, an organization that promotes women in the field of crime writing.

Born in New York City, Dunlap entered Bucknell University as a math major, but quickly switched to English. After earning a master’s degree in education from the University of North Carolina, she taught junior high before becoming a social worker. Her jobs took her all over the country, from Baltimore to New York and finally to Northern California, where many of her novels take place.

One night, while reading an Agatha Christie novel, Dunlap told her husband that she thought she could write mysteries. When he asked her to prove it, she accepted the challenge. Dunlap wrote in her spare time, completing six manuscripts before selling her first book,

Karma

(1981), which began a ten-book series about brash Berkeley cop Jill Smith.

After selling her second novel, Dunlap quit her job to write fulltime. While penning the Jill Smith mysteries, she also wrote three novels about utility-meter-reading amateur sleuth Vejay Haskell. In 1989, she published

Pious Deception

, the first in a series starring former medical examiner Kiernan O’Shaughnessy. To research the O’Shaughnessy and Smith series, Dunlap rode along with police officers, attended autopsies, and spent ten weeks studying the daily operations of the Berkeley Police Department.

Dunlap concluded the Smith series with

Cop Out

(1997). In 2006 she published

A Single Eye

, her first mystery featuring Darcy Lott, a Zen Buddhist stuntwoman. Her most recent novel is

No Footprints

(2012), the fifth in the Darcy Lott series.

In addition to writing, Dunlap has taught yoga and worked for a private investigator on death penalty defense cases and as a paralegal. In 1986, she helped found Sisters in Crime, an organization that supports women in the field of mystery writing. She lives and writes near San Francisco.

Dunlap and her father at the beach, probably Coney Island. ”“My happiest vacations were at the beach,” says Dunlap, “here, at the Jersey shore, at Jones Beach, and two glorious winter weeks in Florida.”

Dunlap’s grammar school graduation from Stewart School on Long Island, New York.

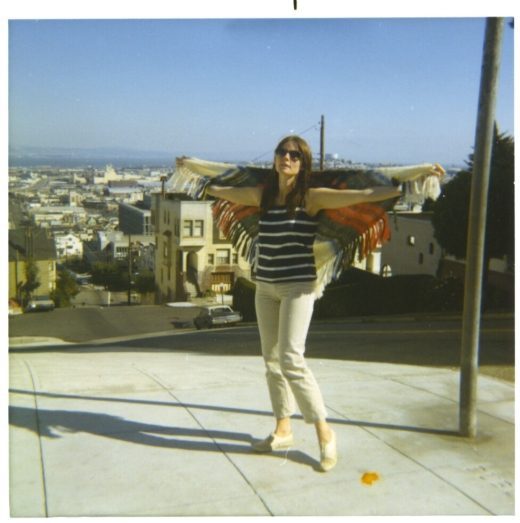

In 1968, Dunlap arrived in San Francisco; this photo was taken by her husband-to-be atop one of the city’s many hills. Dunlap recalls, “It’s winter; I’m wearing a T-shirt; I’m ecstatic!”