Death and the Arrow (4 page)

A FUNERAL IN THE RAIN

London hardly noticed the passing of a boy like Will. The great city lumbered on its busy way, untroubled by the loss of yet another of its poor children, closing up over the gap he had left. Soon it would be as though he had never existed.

Or so things might have been, had it not been for Tom Marlowe. Whatever his father might think — and he and his father had barely spoken since their argument in the coffee house—Tom felt a bond with Will that even death could not break. He was true to his word, and with Dr. Harker’s help, he used the money Will had given him to buy a coffin; Will would not be surgeons’ meat.

On a day of constant and fitting drizzle, Will’s young body was laid to rest in the churchyard of St. Bride’s on Fleet Street. As the church bells chimed, a flock of jackdaws burst from the steeple, calling out and flying off toward the river, and a seagull cried forlornly from a nearby chimney top. The church spire jabbed the sky.

The only face in the graveyard that was not downcast belonged to the sexton, who leaned against the wall at a respectful distance, puffing on a clay pipe, leaning on a shovel, waiting to fill in the hole he had dug the day before. One grave was much like another to him.

The rain blackened the headstones and soaked into the heap of clay beside the grave; it mingled with the tears of the mourners as they said their goodbyes to Will and turned away. Tom found it hard to leave the grave-side but let himself be led away by Dr. Harker. The sexton tapped out his pipe and picked up his shovel.

Will Piggot had been a popular character and the churchyard was full of the most extraordinary-looking people—molls, rogues, and cutpurses—but Dr. Harker had greeted them all with the same civility as if they had been Justices of the Peace. He had taken control of the proceedings as Will’s father might have done, had he not drunk himself to death five years before, and it was greatly appreciated by all who came—particularly Tom, who could never have managed without him. But everyone knew Tom’s part in the proceedings.

“He’s a good lad, though, ain’t he, bless him, seeing our Will done right?” said a pale, skinny, pockmarked girl as she patted Tom on the shoulder. “And him from a decent home and everything.”

“That he is, Bess. You done him proud, boy—and yourself.” There was a murmur of agreement and Tom saw Dr. Harker smiling through the crowd. He felt himself blushing and looked at his shoes.

“But who could’ve done such a thing?” said a large woman, sobbing into a silk handkerchief.

“I dunno, Poll,” said a rat-faced man, “but if I finds him, I’ll play the surgeon with him and that’s a Bible promise.”

“Not if I finds him first,” said another, pulling back his coat to show a brace of pistols tucked in his belt. “These here pops will see the job done true.”

And so it went on. Tom listened to it all and wondered if they would ever know who had murdered Will and why. After all, if these people did not know, then who would? Tom was once again running through recent events in his mind when he heard the grating creak of an upstairs window being opened in a house next to the churchyard.

A housemaid unfurled a Persian rug, flicking with a practiced snap, tossing dust and specks of dirt into a little cloud as she did so. The brightly colored rug shone in the grayness, swirling and shimmering as it was shaken.

Snap!

And

snap!

again. Then, as the rug was pulled back in through the window, Tom saw a man standing in the shelter of the doorway below. He was keeping out of sight as well as out of the rain. And he was watching the churchyard.

Tom wove his way through the mourners and the gravestones, trying to keep sight of the man as he did so. The drizzle and the gray gloom made it impossible to make out any of the man’s features, but he was tall and broad and dressed in black.

Tom reached the path and walked briskly out through the gate and into the street. The man saw him and began to move off, bringing his hat down even farther over his face. A brewer’s cart passed by between Tom and the stranger; when the cart had passed, the man was gone. Tom searched the street, but there was no sign of him anywhere.

Dr. Harker had come to the railings of the churchyard to see what the matter was. “Tom!” he called. “Is everything all right?”

“Yes,” said Tom after a moment. “It’s nothing.” He gave one last look up and down the empty street and then walked back to join the doctor.

“What’s troubling you?” said Dr. Harker.

“I thought I saw someone.”

“Ah, Tom,” said the doctor kindly. “Grief can play all kinds of tricks.”

Tom guessed the doctor’s meaning and shook his head. “No, Dr. Harker. Not Will. The man I saw was real enough. And he did not want to be seen.”

The doctor shot a quick glance back to where Tom had been standing. “But you did see him, Tom? Would you know him again?”

“No, sir,” said Tom. “He hid his face. He was a big man, though—very big.”

Just then Tom and the doctor became aware of someone standing next to them. They turned and saw that it was one of the mourners; a young man, only a few years older than Tom.

“Dr. Harker,” he said. “And Master Marlowe. I have been asked to come across and give our thanks to you sirs for what you’ve done today. There’s not many who would have done the same, and we thank you for it. I thank you for it. Will was as good as family to me and I miss him sore as burning.”

“It was the least we could do, Mr. . . .”

“Carter is my name,” said the man. “Ocean Carter.”

“Ocean,” said Tom with a smile. “Will often talked about you and was always singing your praises. He wanted to be like you, I think.”

Ocean’s eyes loaded with tears. “Thank you kindly, Master Marlowe,” he said.

“Call me Tom.” They shook hands.

“If I can ever be of any assistance to either of you gents, just let me know. They know me in the Red Lion Tavern in Seven Dials. You can leave a message for me there.” With that, the young man turned and walked down the path and out of the churchyard.

Eventually the other mourners began to leave, each one shaking Dr. Harker’s and Tom’s hand in turn. When they had all gone, Tom turned to the doctor. “Dr. Harker, I want to thank you for all you’ve done for me—and for Will.”

“I was happy to do it, Tom,” said Dr. Harker with a smile. “I only wish I could have known Will. He was obviously quite a lad, much loved by those who knew him.”

“Yes,” said Tom. “I think he was. He was loved.” Dr. Harker patted him on the shoulder and smiled. “I have another favor to ask of you, Doctor,” Tom went on.

“Ask away.”

“Will you help me find out who killed Will?”

Dr. Harker smiled a wry half-smile, then looked up at the sky for a minute before turning back to say, “Yes, Tom, I will. But it might be dangerous. . . .”

Suddenly Tom became aware of a figure bent over Will’s grave. “Hello?” he called out nervously. The man did not reply and Tom started to walk slowly toward him. “Hello?” he said again. The man turned to face him; it was his father.

Neither father nor son spoke for what seemed like minutes.

“Tom?” said Mr. Marlowe at last.

“Father.”

“I’m not good at talking, Tom, you know that,” said his father, seemingly to his own shoes. “I print other folks’ words all day long, but the ink just seems to dry up when I try and make my own. Oh, I’ve got plenty of words in here,” he said, patting his chest. “I just can’t seem to get them out.”

Tom smiled. “Let’s just shake on it, then, shall we, Father?”

“That would be just fine,” said his father, and they shook hands. “I must get back now, Tom—there’s a lot on.” And he hurriedly stuffed a paper package into Tom’s hand, tipped his hat to Dr. Harker, and walked briskly out of the churchyard.

Tom opened the package. Inside the paper was the pocket watch his father had given him. On the paper was printed, in an elegant typeface, the words “You are a good lad, Tom. Your mother would be proud of you.”

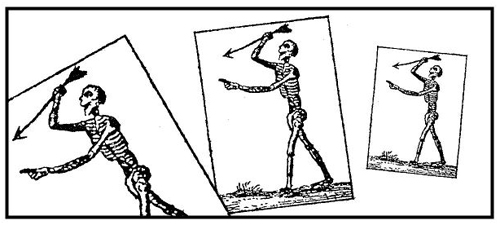

DEATH AND THE ARROW CARDS

"So what shall we do first?” asked Tom impatiently a few days later, breaking the ticking silence in Dr. Harker’s study. The doctor sat back in his chair and put the tips of his fingers together, tapping them gently one against the other.

“Well, Tom,” he said, “first of all we have to look at the facts at our disposal.”

“But . . . but we don’t

have

any facts,” said Tom, looking puzzled.

“On the contrary, we have lots of facts. We simply do not know, for the moment, what they mean.” Tom looked even more puzzled. “Come, come, Tom. What do we know?”

Tom furrowed his brow and shrugged his shoulders. “Well, I suppose we know that Will was murdered.”

“Excellent. We know that Will was murdered,” said Dr. Harker, blushing slightly as he realized how harsh the words sounded. “Sorry, Tom.”

“It’s fine, sir,” said Tom, managing a weak smile. “I know what you mean.”

Dr. Harker nodded. “But,” he went on, “we don’t know why or by whom.”

“That’s what I mean,” sighed Tom. “We don’t know anything. Anything useful.”

“Ah, but we know about the card, do we not?”

“The Death and the Arrow card. Yes,” said Tom. “We know that someone has been killing people and leaving cards on them. But how will that help us find whoever murdered Will?” Tom got to his feet and went over to the window. “Could it have been the Mohocks?”

“I don’t think so. It is beyond their wit, I think. Besides, between you and me, Tom, I think the newspapers make too much of the Mohocks. These scare stories sell papers, lad, but this is too deep for drunken rakes.” Tom looked out of the dusty windows at the sea of rooftops.

“Try to think, Tom, of anything Will might have said that could give us a clue. You told me he had a job?”

“Yes,” said Tom. “I was, well, surprised. And he was a little put out by my surprise.”

Dr. Harker smiled. “Did he tell you what the job was?”

“No . . . he told me it was secret and that he could not tell.”

“A secret, you say?” said Dr. Harker. He was playing with the curls at the end of his long powdered wig— something he always did when deep in thought. “Did he tell you anything about the job? Anything at all?”

“No,” said Tom, shaking his head. “Nothing.” Dr. Harker sighed and closed his eyes. “No! Wait!” Tom shouted suddenly, making the doctor jump and almost tug the wig from his head. “He did! He did say something.” He frowned with the effort of bringing back the words; the exact words. “He said . . . he said . . . yes, that’s right—he said it was the opposite of what he normally did.”

Dr. Harker leaned forward. “That is very interesting, Tom, is it not?”

The doctor stood up and looked out of his window. Tom was pleased to have said something of interest, but he failed to see

why

it was of interest. Dr. Harker turned and, seeing the bafflement on Tom’s face, he smiled. “And what was it that Will normally did?” Tom blushed. “Come, come, Tom. It is no secret, is it? And Will was not embarrassed by his profession, now was he?”

“He was a pickpocket, sir.”

“That he was, Tom, and by all accounts a very skilled one,” said Dr. Harker, patting Tom on the shoulder. “Now, what would the ‘opposite’ of picking someone’s pocket be, I wonder?”

“Putting something

into

someone’s pocket?” said Tom, who instantly felt that he had said something stupid. And when Dr. Harker slapped his palm against his forehead, he was sure of it. But no . . .

“That’s it!” cried the doctor. “He was putting something

into

pockets. So, Tom, can that fine brain of yours hazard a guess as to what that something might have been?”

“The cards!” gasped Tom, surprising himself with the thought.

“The cards.”

“But why?”

“Why indeed? Well,” said Dr. Harker, sitting down once more, “suppose you were hunting a group of men—”

“Hunting?” said Tom.

“Yes, hunting. Suppose you want them to know they are being hunted. You want them to fear for their lives, but you do not want to be seen.”

“I don’t understand,” said Tom. “What has this to do with Will?”

“Everything,” said Dr. Harker. “Because you hire a pickpocket—one whose skills you have seen and admired—and you get him to place cards in the pockets of the men you plan to kill.”

“Will!” exclaimed Tom.

“Precisely. The cards are designed to instill fear and panic into the recipients. They are calling cards from Death himself!

“The Death and the Arrow cards,” muttered Dr. Harker, getting to his feet. “Come, Tom. Let’s take some air.”

And so the two of them left the house, walking silently together for a while in the mild spring morning, the doctor tipping his hat and saying good morning to passersby, as he always did. They ambled along in no particular direction—or so Tom thought.

Finally he broke the silence. “Dr. Harker?”

“Yes, lad?”

“Do you think Will was killed by one of the men he gave a card to, or by the man he was working for?”

“I do not know,” said Dr. Harker. “There is still so much we need to discover. For instance, Tom, why do the cards show Death holding an arrow?”

“Because that is how the murderer kills his victims?” said Tom.

“Yes, yes,” said the doctor. “But

why

does he kill them with an arrow?” Tom looked confused and Dr. Harker smiled and clapped him on the back. “If the murderer wanted to simply frighten those men, then why not simply show a figure of Death? Death can be shown with an arrow, a scythe, a sword, or nothing at all. He could have killed them in any way he chose. Using arrows seems an awful lot of trouble to go to. No, Tom—the arrow must have some significance in this whole business.”

“But what significance?” said Tom.

“We do not know. We need to find out more about the Death and the Arrow victims. They hold the secret to their murderer and to Will’s.”

“But how shall we do that, Dr. Harker?”

“Well, I think we may find some small degree of illumination in this establishment. . . .”

Tom noticed that they were now standing outside a coffee house he had never seen before. In fact, he had been so wound up in what Dr. Harker was saying, he had no idea where in the city they were.

“Remember the first victim, Tom—the man called Leech. Do you remember Purney asked, quite correctly, how it could be possible for the man to have been killed once by natives in America and then a second time, here in London?”

“Yes,” said Tom. “But —”

“Well, there are few certainties in life, Tom, but one thing you can be sure of is that a man cannot be killed twice. Either he was not killed in America, or the man who was killed in London was not Leech.”

“But his own mother identified him,” said Tom.

“That she did, Tom. But was she telling the truth? Let us find out, shall we? She owns this very coffee house.”

Tom looked at Dr. Harker and smiled. He really was a remarkable man. “But how did you find her?” he asked.

“Oh, it really was not very difficult. The constable who took the details was more than happy to talk for the price of a jug of gin. Shall we go in?”

“After you, Dr. Harker,” said Tom with a grin.

“Most kind, Tom,” said Dr. Harker, pointing upward with his cane. “And perhaps you might care to look at the sign on the way in.”

Tom followed the direction of the doctor’s cane and there, hanging from a sinuous tangle of wrought-iron curlicues, was the coffee-house sign—a gleaming golden arrow!