Death in the Sun

Authors: Adam Creed

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #FF, #FGC

Adam Creed

Title Page

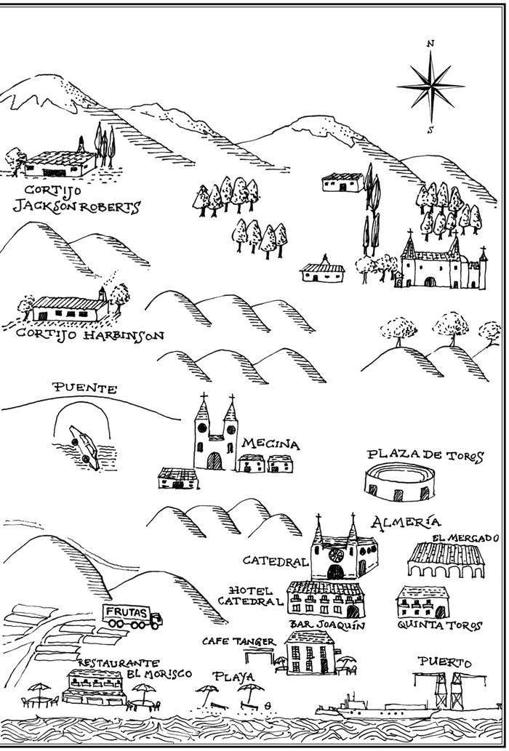

The Alpujarras

Maps

PART ONE

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

PART TWO

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

PART THREE

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

PART FOUR

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

PART FIVE

Thirty-two

Thirty-three

Thirty-four

Thirty-five

Part

One

Acknowledgements

Glossary

By the Same Author

About the Author

Copyright

‘Fui piedra y perdí mi centro

y me arrojaron al mar

y a fuerza de mucho tiempo

mi centro vine a encontrar.’

‘I was a stone and lost my centre

and was thrown into the sea

and after a very long time

I came to find my centre again.’

(Traditional song)

Jadus Golding pauses on the corner, finds a shadow and checks his watch. For an instant its indigo and bejewelled dial makes him feel good about himself, but then he remembers the price it came at. He looks from the time to the sky and sees a leaf, falling. The trees are heavy with leaves and he knows that if he catches the leaf, then luck will come to him. He could do with it.

He holds out his hand, spreading his fingers, then he sees Brandon, walking slow with his hands plunged deep down the front of his Sean Pauls. Jadus closes his hand into an empty fist. The leaf is on the ground.

Jadus runs a few steps, to keep Brandon in sight. He pauses when Brandon pauses to let the traffic go; crosses when Brandon crosses. They proceed in this ill-tailored tandem all the way up to Spitalfields, and all the way, the Limekiln estate comes in and out of view, like an island in a high sea. This makes his blood sluice. He is so close to Jasmine and Millie, but cannot call on his lover and their daughter.

The streets thicken and suits mix with jeans; summer frocks with

salwar kameez

. Brandon slows, turns into the entrance to the market, and stops. Jadus immediately recognises the man he is talking to, which gives him plenty cause for concern. Brandon, so long a friend, has been in hiding since he was shortlisted for the manslaughter of a nineteen-year-old student who just happened to be crossing the road in the aftermath of a job on the Seven Sisters Road – so why is he talking to a policeman?

A Cherokee Jeep slows up and Brandon nods at it, makes a circle in the air with his finger and carries on talking to DS Pulford.

As the Cherokee cruises towards him, its windows blacked out, Jadus pulls his beanie hat down. He gives the Limekiln tower a long, last look, and slopes into Flower and Dean Street, drawing shapes of what he will have to do, if Pulford doesn’t get off his case.

He scrolls through his phone, sees the name is still there:

Staffe Work; Staffe Mobile.

He deletes one and then the other, but knows that this particular policeman will always be there – everywhere he goes.

Slowly, he realises that he is not dead.

He is accustomed to this process but lately it has been complicated by the fact that gunshot awakens him. Birds flap up into the walnut tree, scared by Paco the Frog’s automated gun crow.

The pillows are wet on his neck and the sheets are knotted around his ankles. His fever comes and goes but it has been on the wane this last week. Tomorrow, his friend Manolo is taking him to the hospital in Almería where they will, hopefully, appraise his healed wound a final time. They will chastise him for rushing his rehab, but this latest setback will be his last, he promises himself.

The ceiling is high and the poplar beams are varnished. The house martins circle in the pale morning. Beyond the fringe of silver chains, hanging by the open door to keep the mosquitoes away, the low sun is becoming brilliant. It seems that winter will never come.

Near, mules clatter down the cobbled track that runs by his rented house and into the

campo

. The sweetness of Frog’s black tobacco swirls up through the leaves of the walnut tree.

He pushes himself upright in the bed and touches his soreness. It is less tender than yesterday. This time, he must let it heal completely, stay free from infection.

Frog calls to his dog and Staffe walks across his bedroom’s terracotta floor, warm already, and parts the silver chain

cortinas,

blinking. Beyond the walnut tree, wisps of cloud strand the sky and the massif of Gador is far away, between him and Almería. Tomorrow Manolo has promised him lunch at his

tio

’s bar – an Almerían institution, so he claims.

Staffe picks his phone from the crude, chestnut dressing table and looks for messages. Not a sausage. How his stomach pines for sausage, the English way.

*

A line of men lean against the thick, oak counter of Bar Fuente, arguing fiercely and banging fists. Some wear broad-rimmed straw hats, check shirts and drill trousers tied at the waist with rope; others, younger, are in blue cotton overalls and baseball caps sporting the logos of local plumbing and electrical suppliers. In front of them, on the bar, are rows of tiny white cups and saucers with ferocious coffee alongside small goblets filled to their brims with

sol y sombre –

a breakfast tipple of brandy and anis.

Staffe makes his way to the

comedor

and the locals nod and smile. He says to Consuela, ‘The usual,’ and she smiles sheepishly, her eyes darting to the floor. Staffe chides Frog, for setting his gun crow too early in the morning. Frog pushes back his dog-eared beret, says something indecipherable in reply, then looks Consuela up and down. She has a broad face, her bones are fine and she is taller than most of the men. She is not from these parts, but for some reason has stuck around – perhaps it has something to do with the child she has. She didn’t arrive in Almagen with the child. Frog says something else at her and laughs – like a frog, his big eyes bulging. She scuttles into the kitchen.

As he waits, Staffe looks at some new posters on the wall. They are handwritten in an ornate font with renditions of paintbrushes, books and musical notes as a border. The posters are all slightly different, but each advertises a final decisive meeting with the Junta to determine whether Almagen will be awarded its Cultural Academy. It has been the talk of the village. It will revitalise the place, secure its future.

Bar Fuente, like Staffe’s house, is in the lower

barrio

– the oldest part of the village. The Moors built it in the sixteenth century when they were banished from Granada. Later, the village spread up the hill towards what became a main road, the

carretera.

Each

barrio

has a square and a fountain. In these parts, where the melting snow from the Sierra Nevada flows, water is priceless.

Consuela brings Staffe his

tostada

with tomato and olive oil, a glass of orange juice and

café con leche

.

‘Hey, Guilli!’ says Manolo, picking up a

sol y sombre,

coming to join him. As he brushes past Consuela, Frog says something and Manolo blushes.

‘Guirri!’ calls another.

‘No, Guillermo, you idiot.’ It’s Manolo’s joke – to shorten Guillermo, the Spanish for William, to Guilli. A

guirri

is an outsider, implicitly unwelcome. ‘They’re idiots,’ says Manolo, plonking down a plastic bag on the floor and sitting heavily on the chair opposite Staffe, his torso broad and deep, as if he is not to scale. He nods and smiles at Staffe. His teeth are white and good, odd in these parts, but his skin is dark as stained oak and rough from the sun and the

sierra

winds. Manolo is the village shepherd – El Pastor, and probably a few years younger than Staffe, but the ravages of the sun and wind make him seem older. Frog calls him a stupid goat. Someone else calls him a goat fucker. Manolo ignores them: hurt, but seeming as though he has heard it all before. The lines on his forehead deepen and his shoulders hunch an extra degree. He says, ‘Tomorrow, Almería. You’re still good to go?’ as though apologising for something.

‘Of course,’ says Staffe.

Frog shouts across, ‘I hear your brother is back, the one who got all the brains!’

Manolo pushes the bag towards Staffe with his foot. ‘Tomatoes and peppers, from my

huerta

.’ He swirls his

sol y sombra

, the goblet like a thimble in his enormous hands.

‘Show my friend here your hole,’ calls Frog, imploring Staffe with his wide, bulging eyes. A cluster of the men from the bar turn, urging him, and Staffe reluctantly lifts his shirt. He has done this a dozen times but he manages a smile. One of the younger men comes across, tipping back his baseball cap, crouching, prodding the baby-pink tissue of his two scars: the one between his hip and the navel has healed well but the other, between his heart and the pit of his arm, weeps, having reopened a month ago when a bigoted chump from Mecina, the next village, had started on Manolo. Staffe stepped in, and so did the chump’s friends. Strong as Manolo is, they took quite a hiding.

He swallows away the memory of where the two bullets came from, how long it has been since the doctors at City Royal cheated death, saved the fugitive Jadus from becoming a murderer. It seems a lifetime ago now.

Today, he will do his physio and spend an hour brushing up on his conjugations, then he will meet his young nephew, Harry, from school. They will walk up the mountain together, to El Nido, his sister Marie’s

cortijo

where she lives with the ne’er-do-well Paolo. Meanwhile, he and Manolo sit together. Slowly, the bar thins out.

Staffe says to his friend, ‘Your brother? You never mentioned a brother.’

‘He went away. He is barely anything to me.’

‘Wouldn’t it be nice, to have some family with you – especially with your father away. The family line is what we call it.’

‘Some families are maybe best without a line.’

Frog bangs an empty glass on the counter, shouts something thick and fast to Consuela, who is in the kitchen. The other old goat still at the bar laughs, but Consuela looks hurt and Manolo stands, slowly.

Consuela shouts, ‘No. Lolo, no!’

Manolo walks towards Frog who says, ‘Sit down, you thick lump.’ Manolo reaches out with a big hand and Frog’s friend grabs his forearm, but Manolo gets Frog by the throat anyway, launches him into the wall with one hand around his throat. Frog’s beret falls to ground and his feet twitch in the air. Manolo puts his free hand to his hip, where Staffe sees the carved handle of a knife protruding from a plaited, makeshift belt fashioned from baling twine.

Staffe shouts, ‘No!’ as the colour drains instantly from Frog’s face. Salva, the bar owner, rushes in from the store room, throws himself at Manolo, grabbing him round the neck. But Manolo stands firm and still and Frog’s feet twitch. He squeals, high pitched, like air from a balloon.

Consuela walks through the hatch at the end of the bar and puts a fine hand on Manolo’s massive, taut forearm. She whispers, ‘Please. Let him go. For me.’

Frog drops to the floor, like a sack of beans from a mule. Manolo returns to the table, his eyes empty and cold. He reaches for his hip and pulls his knife, cuts open a tomato and offers a slice to Staffe. ‘My tomatoes are the best.’ The knife has a goat’s head intricately carved for its handle. Seeing Staffe looking, Manolo says in his little voice, ‘I carved it myself.’

Staffe nods at the posters, says, ‘You could get involved in the Academy.’

‘That’s not for us. This lot just want to make off with the money from the government. One man’s culture, another man’s crime.’ He runs his blade through another tomato and Consuela brings him a plate of bread. They don’t look at each other, nor exchange even pleasantries.

*

Staffe finds slim shade by the church in the middle

barrio

. He presses his back to the stone, which is warm. A couple of mothers stand by the fountain watching their young play. The bells peal and before the final ring echoes around the fringe of houses, the children rush through the arched, filigree gate of the school cloister and into the square. The mothers call out to their young but are ignored.

A nun brings a lone child to the ironwork gate. She pats him on the shoulder and points up the mountain, ushering him away. Harry looks sad and Staffe calls out to him. Harry’s face lights up when he hears his name, but becomes instantly glum. He walks towards his uncle briskly, head down. ‘I can walk home on my own.’

Staffe raises a bag. ‘I have tomatoes and peppers from Manolo’s

huerta

.’

‘His garden, you mean.’ Harry walks off up the steep, narrow alley that leads to the main road. At the top of the hill, he drinks lustily from a fountain. When Staffe catches up, Harry holds his uncle’s hand and they cross the Mecina road, take the goat track into the sierra.

‘You don’t know how lucky you are, living here,’ says Staffe.

‘Why can’t I stay with you in the village?’

‘Your mum and Paolo live up the mountain. And you have a new brother or sister about to come along.’

‘There’s nothing to do up there.’

‘What about the baby?’

‘It will only make things worse. You know how small that house is.’

Staffe wants to tell him that he will look back on these days and marvel. ‘You can learn the land. And you should ask your friends up to El Nido. You could make a camp and have them to sleep over.’

Harry looks up at Staffe as if he is deciding whether to confide a secret. He says nothing.

They walk briskly for twenty minutes, Staffe suffering in the heat, but when they reach the

cortijo

, Harry runs past the building, sits on the edge of the

balsa

, a circular, concrete pond that holds water for the land, and for washing. Normally, his feet dangle in the water, but not today.

Marie is chopping peppers outside the stone

cortijo

, which has a kitchen cum living room and a small bedroom either side. The shower is outside and the toilet is wherever takes your fancy. Paolo started on the building work with a vengeance, but as summer hotted up, his mission soon petered out into long afternoons sat on the veranda, smoking his way through his own supply and drinking the local

terrano

wine that comes by the five-litre. Marie fries the peppers, adds beaten eggs to a skillet and rustles up a

revuelta

.

They eat and drink and watch the shadowless enormity of the valley. Paolo talks about what he has planted and how it’s hit and miss but next year will be better.

Staffe thinks, ‘Yeah, right.

Mañana

,’ but says, ‘What will you do in the winter for fuel? The locals have started bringing in their wood.’

‘We’ll do it when it gets cooler,’ says Paolo.

‘Surely, when it gets cooler you’ll already be needing it.’

Paolo says, ‘They’ve thrown the towel in.’

‘What?’ says Staffe.

‘Can’t we let our lunch settle?’ says Marie, gathering the dishes and looking daggers at Paolo. ‘We’re away from the world here. That’s supposed to be the point.’

‘Who’s thrown the towel in?’ asks Staffe.

Marie takes the dishes away and as soon as she is out of earshot, Paolo says, ‘I saw it on the telly in Orgiva. It’s ETA. They have stopped for good.’

Staffe watches Marie at the sink by the door, scrubbing the skillet. When she is done with the pan, she fills a bowl for the dishes, starts singing a Pretenders song. She has a beautiful voice. He says to Paolo, ‘If Marie didn’t want you to say anything, you shouldn’t have said anything.’

‘But she says you’re . . .’ He lets the words drift to nothing.

Staffe goes to Marie, says, ‘Sing that song again. What is it?’

She removes the muslin from a cheese that Manolo had brought round last week. ‘He told you, didn’t he?’

‘What does it matter?’

‘It matters. That’s the problem.’

‘It will be winter soon. You can’t shower outside in the winter.’ He kisses her on the forehead and starts to dry the dishes.

Marie sings, ‘Though you are far away, I know you’ll always be near to me.’ She cuts a slice of cheese, reaches out to Staffe with a piece, pops it in his mouth.

It conjures a memory.

She must see it, because she says, ‘I feel it too, you know, Will. I miss them so badly. But you can’t get angry – that won’t do any good. And surely, if ETA are stopping – that has to be good.’

He chews on the cheese and she leans against him, rests her head on his chest, her ear pressing against his wound. He feels the pain, lets it come, thinks about the heartless bastard who killed their parents: Santi Etxebatteria, who, it seems, is allowed to see the error of his ways and put an end to bad activity. Just like that. Does that make their death even more worthless – that the cause is no longer fought? It is madness to think that way, he knows.

Marie holds up a slice of cheese, says, ‘This is good. Remember when Mum would tell you off for eating it straight from the fridge?’

He smiles, remembers how his teeth would leave their imprint in the waxy cheddar, always catching him out. ‘This is Manolo’s cheese.’