Death Traps: The Survival of an American Armored Division in World War II (33 page)

Read Death Traps: The Survival of an American Armored Division in World War II Online

Authors: Belton Y. Cooper

Tags: #World War II, #General, #Nonfiction, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History

APPENDIX III

Field Deployment of an American Armored Division

During World War II, the U.S. Army had two types of armored divisions. The 1st and the 4th through the 20th Armored Divisions were “light” divisions, each with approximately 11,000 men and 168 medium tanks. The 2d and 3d Armored Divisions were “heavy” divisions, each with approximately 13,500 men and 232 medium tanks. Both types of division had a number of light tanks; because of their extremely limited capability, they were used primarily for reconnaissance. Some felt that the light divisions, based on the highly successful German panzer divisions, would be more effective than the heavy divisions. This was a highly controversial issue among the armored force staff. It was finally decided to leave the 2d and 3d as heavy armored divisions.

The thinking behind the light armored divisions was based on quantitative numbers instead of the qualitative capability. In relative qualitative comparisons of the strength of the main tank forces, the Germans held an edge of at least five to one. Although the light armored divisions did an excellent job, it was soon discovered, after the Normandy invasion, that they did not have the staying power to take horrendous casualties and recover as rapidly as the heavy divisions. As a result, it was decided that in assault operations the 2d and 3d Armored Divisions had to be used to a much greater degree than the lighter units.

Armored Force Tactical Doctrine called for the operation of two types of armored units. The first was the GHQ tank battalion, designed to work with and support infantry divisions. The second was the armored division, a completely self-contained unit containing tanks, self-propelled artillery, and mechanized infantry. In addition, the armored division contained all the necessary support arms, including reconnaissance, combat engineers, supply, medical, and maintenance. This provided a single unit with the firepower, mobility, and shock capability necessary for independent combat operations. The mission of the armored division was not to make the initial breakthrough but rather to exploit the breakthrough made by the GHQ tank battalions and infantry divisions.

The armored division had the capacity to supply itself for three days without outside assistance. Its immediate objective was not to engage other enemy armored units but instead to bypass them and attack artillery and supply units and destroy enemy infantry reserves before they could deploy. By not dissipating its armored striking power by engaging enemy tanks, the division would maintain its full capability.

This tactical doctrine was developed simultaneously by a group of young British and American officers in the late 1920s and early 1930s. By adopting the tactics and basic mission of horse cavalry and modernizing it with tanks and other mechanized units, an entirely new type of combat unit was created. The Germans obviously came upon the same idea.

An American heavy armored division deployed in the following manner: The basic unit consisted of a division headquarters, three combat commands, and the division trains. The division headquarters consisted of the headquarters company, a reconnaissance battalion, and a signal company. Each combat command consisted of a headquarters, a recon company, two tank battalions with two medium tank companies and one light tank company each, an armored infantry battalion, an armored field artillery battalion with eighteen M7 self-propelled 105mm howitzers, an armored combat engineer company, an ordnance maintenance company, a medical company, and a supply company. The division trains consisted of their headquarters, the ordnance battalion headquarters company, the medical battalion headquarters company, and the supply battalion headquarters company. In addition, a heavy armored division had attached to it an antiaircraft battalion, a tank destroyer battalion, and a heavy artillery battalion of 155mm GPF rifles mounted on an M12 tank chassis. This gave the division a total strength of approximately 17,000 men and 4,200 vehicles. Had the division ever gotten on the road in single file, in normal march order interval, it would have stretched 150 miles from the head of the column to the end.

Once the division deployed to exploit a breakthrough, it moved out with two combat commands abreast and one in reserve. Each combat command contained two separate task forces, moving as much in parallel as the contours of the land would permit. The front of a heavy armored division could vary in width from several hundred yards up to twenty miles depending upon the terrain. During the daylight hours, each task force had available four P47 fighter-bombers under the direct control of an air force liaison officer who rode in the lead half-track with the task force commander. The task force’s mission was to advance rapidly toward its objective, leaving any resistance to be cleaned up later by the infantry, which might arrive within the next few hours to two days.

At night the combat elements would coil off the road and form a circular perimeter. The tanks and infantry would form the outer perimeter, and the maintenance, medical, and supply units would be inside, where they could do their work. At daybreak, when the combat units moved out, the maintenance unit commander had to make certain critical decisions. All vehicles repaired and ready for action would be returned to their units. All others would be towed to the next stopping point. If there were more vehicles than the wreckers could accommodate, a vehicle collecting point (VCP) was established. The ordnance company commander would detach a maintenance platoon to establish the VCP and repair the vehicles that were left behind. This could take several days. During this period, the maintenance platoon would be completely isolated behind enemy lines and be responsible for its own security.

After the vehicles were repaired, they returned to their original units, and the maintenance platoon went forward to rejoin the ordnance company. In some instances, there would be several VCPs along the route of advance. As soon as any platoon finished its repairs, it would leave the others and return to the company. By utilizing this system, plus the replacement vehicles brought up each day by the ordnance liaison officer, the combat command was able to maintain its effectiveness during long, continuous operations.

Suggested Reading

Ambrose, Stephen E.

D-Day June 6, 1944.

Simon and Schuster, 1994.

———.

Citizen Soldiers.

Simon and Schuster, 1997.

Arend, Guy Franz.

Bastogne.

Blumenson, Martin.

Breakout and Pursuit.

Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center for Military History, 1981.

Bradley, Omar N.

A Soldier’s Story.

New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1951.

Cole, Hugh M.

The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge.

Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center for Military History, 1988.

Eisenhower, Dwight D.

Crusade in Europe.

Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Co., 1948.

Green, Michael.

M4 Sherman.

Osceola, Wis.: Motor Books International, 1993.

Houston, Donald E.

Hell on Wheels: The Second Armored

Division.

Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1977.

MacDonald, Charles B.

The Mighty Endeavor: The American Army in Europe.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1969.

———.

The Last Offensive.

Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center for Military History, 1981.

———.

A Time for Trumpets.

New York: William Morrow and Co., 1985.

———.

The Siegfried Line Campaign.

Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center for Military History, 1989.

MacKinder, Sir Halford.

Democratic Ideals and Reality.

London: Royal Historical Society, ca. 1921.

Mellenthin, F. W. von.

Panzer Battles: Classical Account of

German Tank Warfare in WW II.

New York: Ballantine Books, 1956.

Normandie Album Memorial: 6 June–22 Aug 1944.

Editions Heimal.

Scott, Wesley W.

Tanks Are Mighty Fine Things.

Detroit: Chrysler Corp., 1946.

Weigley, Russel F.

Eisenhower’s Lieutenants.

Bloomington, Ind.: University Press, 1981.

Written by the men of the Third Armored Division.

Spearhead in the West: The Third Armored Division.

Frankfurt am Main: Schwanheim, 1945.

Zumbro, Ralph.

Tank Aces: Stories of American Combat

Tankers.

New York: Pocket Books, 1997.

World

War

II

had

many

heroes . . .

BLACK SHEEP ONE

The Life of Gregory “Pappy” Boyington

by Bruce Gamble

With the onset of World War II, when skilled pilots were in demand, Gregory “Pappy” Boyington became the commander of an ad hoc squadron of flying leathernecks. The legendary Black Sheep set a blistering pace of aerial victories against the enemy. Though many have observed that when the shooting stops, combat heroes typically just fade away, nothing could be further from the truth for Boyington. Blessed with inveterate luck, the stubbornly independent warrior lived a life that went beyond what even the most imaginative might expect. Exhaustively researched and richly detailed, here is the complete story of this American original.

“A DEFINITIVE BIOGRAPHY . . .

The story of this brave and paradoxical Marine

is the stuff of legends.”

—W. E. B. GRIFFIN

Author of

The

Corps

Published by Presidio Press.

Available wherever books are sold.

A Mark V German Panther that was knocked out of action at Normandy. An American M36 tank destroyer with a 90mm cannon penetrated the face plate from 100 yards.

A Mark V German Panther destroyed in Normandy by an M4 Sherman’s 76mm gun (hit on the left flank side), near Le Dézert, France (St. Lo sector), July 1944.

An American tank knocked out near Fromentel, France, 18 August 1944.

A Mark V Panther destroyed by overhead artillery fire at Le Dézert in Normandy, July 1944.

An M4 Sherman that was struck in its turret ring, near Ranes, France, 1944. Both turret and hull are damaged, thus making the tank unrepairable.

A close-up of shell marks in the frontal armor of a Panther Mark V, which was struck twice by a 76mm shot at close range, at Le Dézert, France, July 1944.

A T2 armored recovery vehicle towing a disabled M4 Sherman.

One of only two Super Pershing M26A1E2 tanks built, being test fired at Niederaussen, Germany. Weighing 53 tons, its 90mm-70 caliber gun fired at 3,850 feet per second. It was the most powerful tank in Word War II.

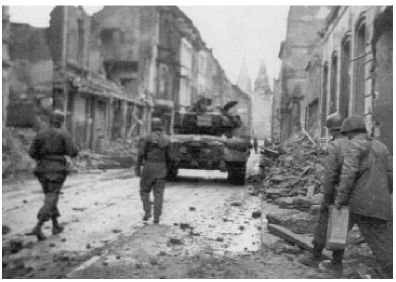

An M26 Pershing G7-32AK approaches the bombed Cathedral Plaza in Cologne. A German Panther Mark V had just knocked out an M4 Sherman.

An M26 Pershing comes around a corner and faces a Panther tank (not in photo). The Panther expects the M26 to stop before firing but gunner Clarence Smoyer’s tank had a gyrostabilizer that let him fire when moving.

The first shot struck the base of a gun mantelet and deflected down through the deck armor killing the German gunner and setting the tank on fire. Smoyer fired two other shots to the flank. Three Germans burned in the tank, while two (seen running) escaped death.

This Mark V Panther burned for two days.