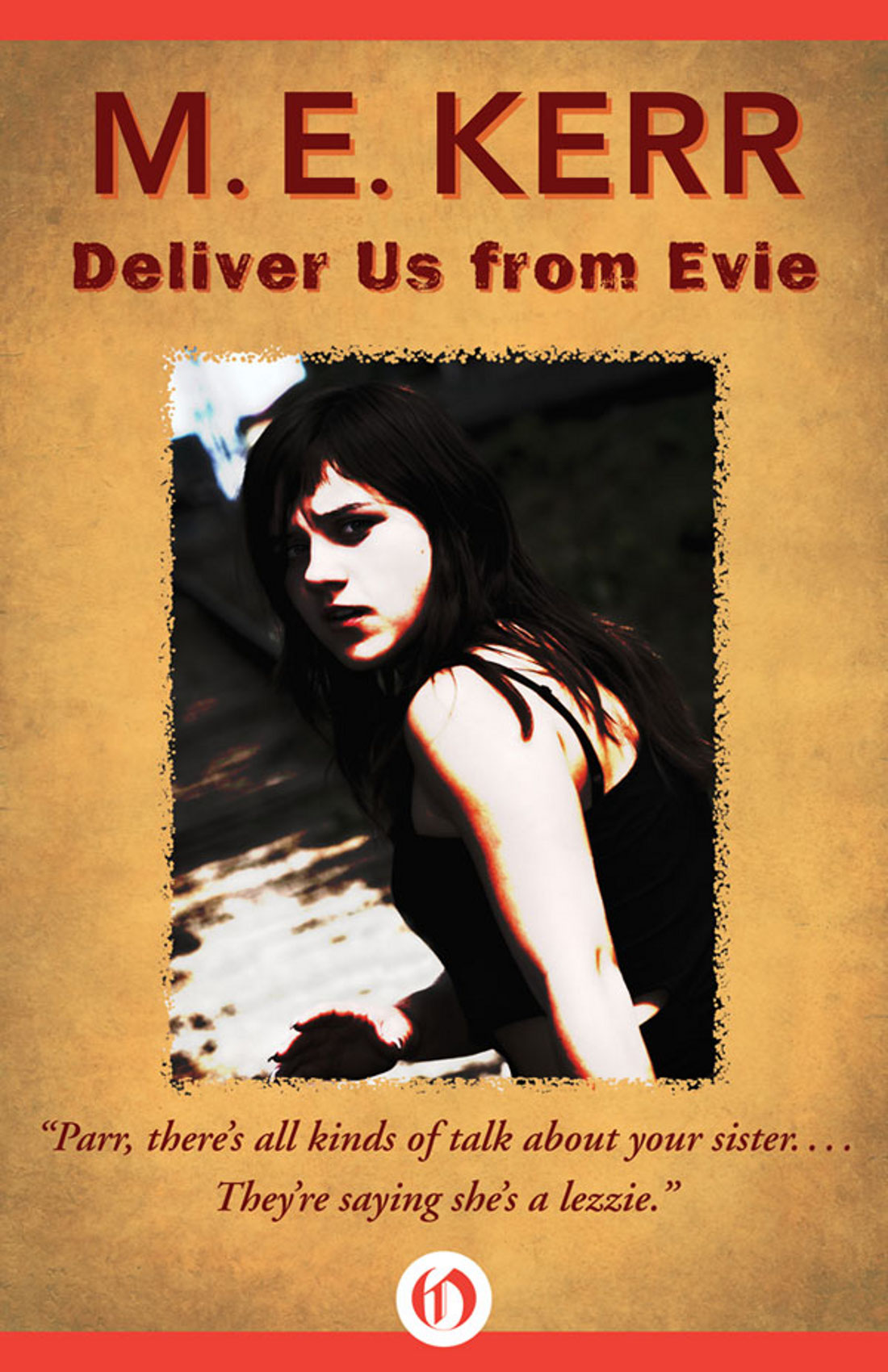

Deliver Us from Evie

Read Deliver Us from Evie Online

Authors: M. E. Kerr

M. E. Kerr

For Robert O. Warren,

skillful editor,

fast walker,

smooth talker …

with thanks for years of help.

A Personal History by M. E. Kerr

P

IG WEEK BEGINS THE

first Monday after Labor Day at County High.

The freshmen and the transfers from Duffton School are “the pigs.”

The seniors are out to get you. They call “SOU-weeeee! Pig, pig, pig!” at you, and they put you in a trash can, tie the lid with rope, and kick you around in it. You learn how to curl into a ball and cover your head with your arms. That happened to me first thing in the morning. I was a transfer junior from Duffton.

Then, in the afternoon, a few got me by my locker. They read my name on the door,

PARR BURRMAN

, and one of them said, “Hey, we know your brother. What’s his name again?”

“Doug Burrman,” I said.

They said, “Not

that

brother! Your other brother.”

“I only have one brother,” I said.

They said, “What about Evie?”

Then they began to laugh. They began to say things like “You remember

him

, don’t you? Doesn’t he live with you? Sure he does! The Burrman brothers: Doug, Parr, and Evie!”

I didn’t mention it when I got home.

“How’d things go, Parr?” my mother said.

“Okay. I’m glad Doug warned me about how to curl up in that trash can.”

“Did they make you roll in the mud?”

“They didn’t have any mud today—but they said we’d better not wear our good clothes tomorrow.”

“Ah, well, I guess they’ll have the pigpen ready tomorrow.” My mother had a tuna fish sandwich ready for me before I changed and went out to do my chores. She said, “They never gave a warning to Doug or Evie. You should have seen their clothes!”

Mother was the reason I was named Parr.

She’d been Cynthia Parr when she met Dad at the University of Missouri. He’d been in the Agricultural College there.

Now my brother Doug was following in his footsteps. Of the three of us—me, almost sixteen; Evie, eighteen; and Doug, twenty—I was the only one who didn’t want to be a farmer.

I could hear the combine working its way through the field out behind the house. I knew Evie was driving the thing. It’d grab the entire plant of corn, strip off its ears, take the kernels, pump them into a storage tank, and dump the rest of the plant back into the field behind it.

Sometimes I’d look at my mother and wonder how she’d ever brought someone like Evie into the world.

The only thing they had in common was a love of reading. Evie wrote some, too, like Mom used to when she was her age. But they weren’t alike in any other way. They didn’t even look alike. Evie had Dad’s height—she was almost six foot—and she had Dad’s brown hair instead of being blond like Mom.

You’d say Evie was handsome. You’d say Mom was pretty.

Then there was the difference in the way both of them dressed.

My mother wasn’t like most farm women, who wear jeans and sweatshirts. She had a few pairs of slacks, but mostly she wore skirts or dresses, and the only time I ever saw her in men’s clothes was sometimes when we were harvesting. She’d bring some sandwiches out to us and she might have on an old shirt of Doug’s or my father’s gloves, maybe my boots, but she was as uncomfortable in men’s things as Evie seemed to be in female stuff.

I knew Mom would hate it if I told her the kids had called Evie my brother.

She was trying hard to change Evie that fall, trying everything, but it was like trying to change the direction of the wind.

H

ALLOWEEN NIGHT THE DUFFS

always invited everyone from nearby farms to come to theirs.

Our town got its name from the Duffs. Their family had founded it way back.

They had a thousand acres. We had a hundred and fifty.

Mr. Duff was a banker, too, and he held the mortgage on most of the farms that weren’t paid off yet, including ours.

Evie didn’t want to go to the party. Way past dark she was still out in the middle of a back field fooling around with a balky diesel engine, welding something that had broken.

My father said let her stay there, what the heck, but my mother insisted Evie come in and change her clothes and go with us.

I could hear them arguing upstairs while my father sat in front of the TV, watching news of hog and corn futures broadcast on

The Farm Report.

“It’d fit you, Evie!” my mother was telling her.

“It might fit me but it doesn’t suit me!”

“Try it, that’s all.”

“Wear a skirt to the Duffs’? I don’t care about the Duffs! That’s your problem, not mine!”

“What’s my problem, Evie?”

“Wishing you were high class is your problem!”

“I am high class.”

“You

were

high class, maybe, back when you were a Parr. Now you’re just a farmer’s wife, Mother—get used to it!”

My father could hear them, too.

He said to me, “Tell those two we’re not going anyplace if they don’t get down here right now.”

I called up, “So long! We’re leaving.”

My mother came downstairs in a long black skirt with black boots and a white silk blouse. Her blond hair spilled down to her shoulders, and she had on pearls my father’d bought her back when they first got married.

I was in jeans, boots, and a white shirt.

My dad was in jeans, boots, and a flannel shirt.

When Evie appeared she was in jeans, boots, and a heavy sweatshirt that said

GET HIGH ON MILK! OUR COWS ARE ON GRASS!

She wore her hair very short, with a streak of light blond she’d made with peroxide. That was as close as she’d ever come to makeup. She’d written one of her nonrhyming poems about it. (Mom called them “statements.”) It began

There’s only a ribbon of color I put in my black-and-white life./Combed back you can hardly see it

,

just like my black-and-white life.

She cocked her hand like a gun and shot at me.

“Let’s go!” she said.

You could see the blue of her eyes all the way across a room. I thought she looked a little like Elvis Presley.

My father guffawed when he saw the sweatshirt. “Where’d you get that thing?”

Evie always talked out of the side of her mouth. “I got it out at the mall. Like it?”

“Evie,” my mother said, “it’s not appropriate to wear to the Duffs’.”

“Why isn’t it appropriate?” my father said. He wasn’t crazy about the Duffs, for one thing; for another, he always took up for my sister.

My mother liked to say that’s how Evie got to be the way she was. She only listened to my father. Listened to him, walked like him, talked like him, told jokes like him.

While Evie drove us over to the Duffs’, Dad started griping about The Duffton National Bank, and how hard they were on the farmers who got behind in their mortgages.

“These are hard times for everybody,” my mother said.

Evie said, “Only difference between a pigeon and a farmer today is a pigeon can still make a deposit on a John Deere tractor.”

My father let out a hoot and gave her back a slap.

“Where’d you hear that one?” he asked, laughing.

In the backseat, beside me, my mother just sighed.

W

E NEVER SAW MUCH

of Patsy Duff because she went to private school and summer camp, but she was home for a long weekend.

I watched her that night and thought of that case, a while back, about the babies being switched in the hospital, each one going home to the wrong family.

Patsy looked enough like my mother to be her daughter. Her blond hair fell down her back and she had that same flirty quality my mother had with people, smiling easily into their eyes, listening nicely, and saying the right things back. She had class, like my mother, and seemed older than seventeen.

“Your husband’s so handsome, Mrs. Burrman,” she told my mother, passing her a mug of cider.

“Oh, Douglas would like to hear that,” said my mother.

“I heard you met him in college.”

Then my mother went into her story about how she never expected to date an ag student, how she always imagined she’d go for a law student or a journalism student, but Douglas just swept her off her feet, she guessed it was those dimples of his, that smile, instant chemistry, she said, and here I am on a farm in Missouri when I always thought I’d be working for a New York City newspaper.

“Were you in journalism school?” Patsy asked, and my mother nodded.

I hung around in the background, smiling. I wasn’t unlike my dad in looks. I was tall and skinny as he was, no dimples but a good smile when I smiled. I didn’t often smile

at

people, as he did. That was more Evie’s style. She’d walk right up and glad-hand them and grin at them.

I stood there hoping Patsy Duff would look my way.

My mother read my mind and said to Patsy, “Have you met my son Parr?”

“Hello, Parr,” Patsy said. She had on a white wool skirt and a red sweater. “Excuse me, please, Mother may need some help ’long about now.”

I watched her walk away. At one end of the large room Evie was down on her knees with her head in a pail of water, ducking for apples, while all the little kids there laughed and clapped.

At the other end of the room the men were gathered around Mr. Duff. He was short and fat, his red face cut with a wide white smile. He had on a blue blazer with gold buttons, and a white turtleneck sweater. He never looked like anyone else in Duffton. Neither did his farm. There was a swimming pool behind the house, and he always had a new-that-year sports car parked in the garage. And not that he ever personally drove a tractor, but if he felt like it there were several of the latest enclosed air-conditioned International Harvesters out near his barn. His help had it real good at Duffarm, which is what the gold sign out front said.

It wasn’t that Mr. Duff didn’t do good things for the town; he did. There was the Duffton Municipal Swimming Pool he’d paid for; there was the Duffton Community Center. And there was the Veterans’ Memorial Statue, center of town—a stone guy in a helmet, charging with a fixed bayonet.

Kids hung things on the bayonet nights they roamed homeward from the movie or the bowling alley. A rubber chicken, a bra, a rubber tire—you never knew what you’d see hanging off it first thing in the morning.

I saw some guys I’d gone to Duffton School with, ones who didn’t finish over at County High, dropouts, farming now. Most of them had their own pickups, and they seemed older than me suddenly, talking farm stuff while they shot pool in Mr. Duff’s rec room. I hung out with them. Some of them planted and harvested for us, since Doug was in college. One of them was Cord Whittle, who had a crush on Evie. He kept talking about how she could do anything a man could do, then he nudged me and said, “Well,

almost

!”

We didn’t stay late.

Dad had an appointment early the next morning with someone from the Rayborn Company. They serviced farms with things like stacked cages for chickens that never got outside, layers that lived several birds to a cage and never even saw a rooster. Modern farming! It made Mom and me sick to think about it. But Dad wasn’t going into the chicken business. If anything, we’d cut way back on all livestock but hogs. We had new ones from Europe that were supposed to produce a lean, low-cholesterol pork, since the whole country seemed to be on a health kick.