Delivered from Evil: True Stories of Ordinary People Who Faced Monstrous Mass Killers and Survived (19 page)

Authors: Ron Franscell

Tags: #True Crime

After Hennard’s ashes began their journey to the sea, Suzanna joined a small group of survivors on a clandestine tour of the killing floor.

Locals had been gossiping that the cafeteria, like the McDonald’s in San Ysidro, might be torn down, erased from the community’s memory altogether. Instead, Luby’s had gutted the restaurant, ripped up the bloody carpeting and scrubbed the bloodstains off the concrete beneath, patched the bullet holes, expelled the stink of burned gunpowder and death, dumped all the furnishings …exorcised everything but the ghosts that haunted the place.

But on the asphalt outside, in the exact spot under the atrium where her father breathed his last, a dark stain lingered.

It was Al’s blood.

A ONE-WOMAN CRUSADE

The massacre was not yet finished for Suzanna. In her mind, amid the guilt and cold rationale that had failed her when it mattered most, the slaughter of her mother, father, and twenty-one others became part of a bigger battle for survival. If she could replay the day, she would risk everything by carrying her gun into Luby’s for a shot at George Hennard, but there were no replays.

She began to think she could change the past by changing the future.

The people of Killeen wore yellow ribbons while troops from nearby Fort Hood were fighting in Iraq and switched to white ribbons after Hennard’s

rampage. They left flowers and heartfelt messages outside the empty Luby’s shattered windows.

And Texas governor Ann Richards spoke passionately about the need to control the sale and possession of automatic weapons, even though Hennard had purchased his guns—both semiautomatic weapons—completely legally. “Dead people lying on the floor of Luby’s should be enough evidence we are not taking a rational posture,” she said.

For them, that was enough, but not for Suzanna.

Suzanna launched a one-woman crusade to allow Texans to carry hidden loaded handguns if they pass a safety course and get a license. And in 1996, five years after George Hennard’s rampage, it became law, although concealed weapons remained illegal in places such as churches, stadiums, government offices, courts, airports, and restaurants serving alcohol.

Now married to Greg Hupp, the man she was dating at the time of the Luby’s shooting, Suzanna ran for the Texas legislature and won handily. She continued her crusade for gun rights, testifying passionately in Congress and states where fear of random crime had forced a legislative response.

“I’ve lived what gun laws do,” she told them all. “My parents died because of what gun laws do. I’m the quintessential soccer mom, and I want the right to protect my family. What happened to my parents will never happen again with my kids there.”

The media beat a well-worn track to her door. She got airtime with all the major networks and ink in most of the country’s magazines and newspapers. She became the first woman ever honored with a life membership to the National Rifle Association.

After serving five terms in the Texas legislature, Suzanna retired with Greg to raise her two sons on her central Texas horse farm. She has written an unpublished manuscript about her life, the Luby’s massacre, and gun rights, but mostly she jealously guards her time with her children—worrying about lack of time is one of the posttraumatic effects she must endure.

Suzanna now carries a gun with her almost everywhere, hidden in a purse or holster. She even has a special gun purse for her evening wear. She still eats out at restaurants, preferring places where she’s known—and where she knows almost everyone. She always sits where she can watch the door, usually near the back. If a strange, lone man saunters in, she pays closer attention. If a dropped glass shatters on the floor, she freezes for a startled moment.

But she’s ready.

And she never mentions George Hennard’s name, denying him the notoriety that even a single whispered breath grants. He is just “the gunman” or “the killer,” her way of reducing him to the pathetic, unfinished, nameless soul that he will always be to her.

A COLD SKY, WATERCOLORED IN SHADES OF GRAY,

hung low over the parish voting hall on Election Day 2008. Tim Ursin hunkered into his coat and inched along in the long line outside, trying to keep warm. The brisk wind carried a hint of Gulf salt. He’d spent his whole life in these bayous, going on sixty-six years now, and he loved the water, but today wasn’t a good day for fishing. Today was for voting. A black man talking about hope looked like he might win this historic presidential election, not just for Louisiana, but for the country and maybe the world.

“Cold one today,” said the young African American man in his mid-thirties in line ahead of him. He turned his back to the wind, facing Tim.

“It is.”

“Line’s movin’, but I wish it was movin’ faster.”

“Got nothin’ else to do today,” Tim said. “Can’t fish.”

“I hear ya,” the man said. “I love to fish, but today just ain’t the day.”

The young man introduced himself to Tim. He was a truck driver with a family.

“What do you do?” he asked.

“I’m a fishing guide,” Tim said. He reached in his pocket for a business card and the young man saw the silvery steel hook where his left hand once was.

“I hope you won’t be offended,” the curious man said, “but what happened to your hand?”

Tim smiled. People always wanted to know about the hook, even if they didn’t ask. He was used to it. And, hell, he’d told the story so many times in the past thirty-five years, he didn’t mind telling it again.

“It’s okay. I was a firefighter. I’ve been retired from the New Orleans Fire Department since ’75. I was shot a long time ago, in ’73, by a sniper at the Howard Johnson. Lost my arm up to here,” he said, wrapping his good right hand around the stump of his left forearm.

The young man’s eyes flickered with recognition as Tim told about that other cold morning in New Orleans when he crossed paths with a killer.

“I heard about that guy! I was just a little kid, but my parents talked about it,” he said. He stumbled slightly over his next words. “He was …he was a black guy, wasn’t he?”

“Yeah, but he …,” Tim started to say.

“I’m sorry, man. I mean, that you were shot by a …a black man.”

“Hey, you didn’t do it,” Tim assured him. “I appreciate that, but you don’t have to be sorry or feel bad for what somebody else did. Didn’t matter what color he was then, and doesn’t now.”

“Thanks, man,” he said. “But if it happened to me, I just don’t know how I couldn’t be bitter …”

They talked about the shooting as long as they could. Inside the voting area, they parted ways in front of the poll workers’ table.

“I admire you,” the young truck driver said. “I mean, the way you look at it.”

“Life goes on,” Tim said. “Doesn’t do any good to dwell on something that happened a long time ago, you know? Everything has a purpose. Every day’s a gift. You just never know. I just gotta keep moving forward …and not just for me, but for the people around me, too.”

The man smiled, shook Tim’s hand, and was gone.

It’s funny, Tim thought, how the murky water of memory gets churned up on cold mornings.

STRAIGHT UP TO HELL

A chilly drizzle fell on New Orleans all night. For a few hours between the last late-night jazz riffs in the Quarter and the first peal of St. Louis Cathedral’s bells, the only sound was rain. The greasy blue Sunday morning streets, absolved of Saturday night, lay empty under leaden January skies.

Before dawn on January 7, 1973, Lieutenant Tim Ursin kissed his wife and three sleeping children good-bye, left his house, and arrived at New Orleans Fire Department, Station Fourteen, a little before 7 a.m. He was only twenty-nine but already a nine-year firehouse veteran and one of the NOFD’s most promising young officers, maybe even a future district chief. He had spent part of his rookie year at Engine Fourteen, as it was known in the department, and now was coming back to help out his shorthanded buddies.

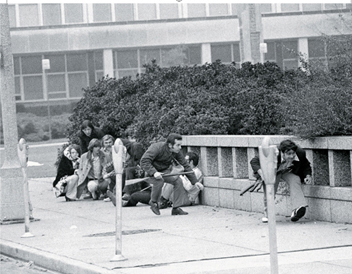

RACIST SNIPER MARK ESSEX HELD POLICE AT BAY FOR SEVERAL HOURS SO SKILLFULLY THAT POLICE (SUCH AS THESE PLAINCLOTHES OFFICERS DUCKING FOR COVER OUTSIDE THE HOWARD JOHNSON MOTEL) BELIEVED THERE WERE SEVERAL SHOOTERS.

Associated Press

Engine Fourteen was a busy station near the center of New Orleans, surrounded by Charity Hospital, City Hall, downtown hotels, some dreary ghetto housing and projects, and one of New Orleans’s forty-two cemeteries, where big rainstorms had been known to pop airtight caskets right out of the waterlogged earth like macabre bubbles. In New Orleans, death and water have always had an uneasy kinship.

But Tim loved New Orleans, the city where he was born. His father had played drums with the great Pete Fountain and some of the Dixieland bands that set the rhythm for the beating heart of the Crescent City. He’d met his wife here and was raising three kids here, too. It had everything he ever wanted, and he never needed to leave. Sure, there was crime, pervasive corruption, decadence, and dreadful poverty, but the city hid it all behind a mask of Old World architecture and sumptuous menus of bayou cuisine, iron-lace balconies, and endless revelry.

Rainy winter Sundays were usually slow for firefighters, so Tim spent the morning helping with mundane chores around the station, sweeping floors, making beds, and washing the trucks. Because nobody cooked on leisurely Sundays, the firefighters usually ordered takeout.

Tim was the extra man today, so he volunteered to make a lunch run to a local burger joint a couple blocks away. He took everybody’s order and was heading to his car when somebody hollered for him to wait while they called another local place to see if they had hot lunches. When nobody answered, he turned to leave, but the firehouse radio beeped twice—the signal for a working fire with visible smoke someplace in the city.

“Engines Sixteen, Fourteen, Twenty-seven, Truck Eight, Three-oh-two,” a dispatcher blared at 10:45 a.m. “Go to Howard Johnson Motor Court, three-three-zero Loyola. Working fire.”

The Howard Johnson was just two minutes from Engine Fourteen, damn near a straight shot. Firefighters scrambled as Tim quickly yanked on his bunker gear and grabbed a jump seat behind the pumper’s cab.

As they pulled up in front of the seventeen-story high-rise hotel, Tim saw black smoke belching from windows on the eighth or ninth floor. This was no mattress fire.

Worse, just six weeks before, a mysterious arson fire had swept through the top three floors of the seventeen-story Rault Center—a luxury office and apartment complex right next door to the Howard Johnson—killing six. Five had leaped to their deaths from fifteenth-floor windows because the firefighters couldn’t pump water high enough and had no ladders tall enough to rescue them. The New Orleans’s Fire Department had reason to be edgy about another skyscraper fire.

Truck Eight, an aerial-ladder truck, pulled up in front of the hotel just ahead of Engine Fourteen, a water pumper. The operator was already setting his stabilizer jacks so he could extend his ladder to snatch frantic hotel guests who were already screaming from upper-floor balconies. But even if he were perfectly positioned, his ladder would only reach the ninth floor. Visions of the Rault Center were already starting to sweep through the heads of the firefighters on the ground.

A district fire chief grabbed Tim amid the chaos of running firefighters, civilians, and cops.

“Come with me,” he barked. “Let’s see what we’ve got here.”

They entered the hotel’s lobby as frightened guests streamed down stairwells from their rooms above. Anxious to know exactly what they faced, Tim instantly made a plan: He would take an elevator up to the sixth or seventh floor, then scramble up the stairs to the fire above. He grabbed two firefighters and started for the elevator but was quickly stopped by armed cops.

“Can’t go up there,” they said. “We got a guy with a shotgun trapped in the elevator, and we’re trying to get him out.”

Blocked from the stairs, too, Tim went back outside. Truck Eight sat empty, its crew working elsewhere. Its stabilizers were set, but there was nobody to operate its ladder.