Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) (706 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) Online

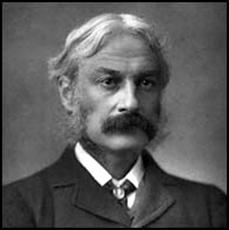

Authors: NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

s

III — Hawthorne

The substance of Hawthorne is so dripping wet with the supernatural, the phantasmal, the mystical — so surcharged with adventures, from the deeper picturesque to the illusive fantastic, one unconsciously finds oneself thinking of him as a poet of greater imaginative impulse than Emerson or Thoreau. He was not a greater poet possibly than they — but a greater artist. Not only the character of his substance, but the care in his manner throws his workmanship, in contrast to theirs, into a kind of bas-relief. Like Poe he quite naturally and unconsciously reaches out over his subject to his reader. His mesmerism seeks to mesmerize us — beyond Zenobia's sister. But he is too great an artist to show his hand “in getting his audience,” as Poe and Tschaikowsky occasionally do. His intellectual muscles are too strong to let him become over-influenced, as Ravel and Stravinsky seem to be by the morbidly fascinating — a kind of false beauty obtained by artistic monotony. However, we cannot but feel that he would weave his spell over us — as would the Grimms and Aesop. We feel as much under magic as the “Enchanted Frog.” This is part of the artist's business. The effect is a part of his art-effort in its inception. Emerson's substance and even his manner has little to do with a designed effect — his thunderbolts or delicate fragments are flashed out regardless — they may knock us down or just spatter us — it matters little to him — but Hawthorne is more considerate; that is, he is more artistic, as men say.

Hawthorne may be more noticeably indigenous or may have more local color, perhaps more national color than his Concord contemporaries. But the work of anyone who is somewhat more interested in psychology than in transcendental philosophy, will weave itself around individuals and their personalities. If the same anyone happens to live in Salem, his work is likely to be colored by the Salem wharves and Salem witches. If the same anyone happens to live in the “Old Manse” near the Concord Battle Bridge, he is likely “of a rainy day to betake himself to the huge garret,” the secrets of which he wonders at, “but is too reverent of their dust and cobwebs to disturb.” He is likely to “bow below the shriveled canvas of an old (Puritan) clergyman in wig and gown — the parish priest of a century ago — a friend of Whitefield.” He is likely to come under the spell of this reverend Ghost who haunts the “Manse” and as it rains and darkens and the sky glooms through the dusty attic windows, he is likely “to muse deeply and wonderingly upon the humiliating fact that the works of man's intellect decay like those of his hands” ... “that thought grows moldy,” and as the garret is in Massachusetts, the “thought” and the “mold” are likely to be quite native. When the same anyone puts his poetry into novels rather than essays, he is likely to have more to say about the life around him — about the inherited mystery of the town — than a poet of philosophy is.

In Hawthorne's usual vicinity, the atmosphere was charged with the somber errors and romance of eighteenth century New England, — ascetic or noble New England as you like. A novel, of necessity, nails an art-effort down to some definite part or parts of the earth's surface — the novelist's wagon can't always be hitched to a star. To say that Hawthorne was more deeply interested than some of the other Concord writers — Emerson, for example — in the idealism peculiar to his native land (in so far as such idealism of a country can be conceived of as separate from the political) would be as unreasoning as to hold that he was more interested in social progress than Thoreau, because he was in the consular service and Thoreau was in no one's service — or that the War Governor of Massachusetts was a greater patriot than Wendell Phillips, who was ashamed of all political parties. Hawthorne's art was true and typically American — as is the art of all men living in America who believe in freedom of thought and who live wholesome lives to prove it, whatever their means of expression.

Any comprehensive conception of Hawthorne, either in words or music, must have for its basic theme something that has to do with the influence of sin upon the conscience — something more than the Puritan conscience, but something which is permeated by it. In this relation he is wont to use what Hazlitt calls the “moral power of imagination.” Hawthorne would try to spiritualize a guilty conscience. He would sing of the relentlessness of guilt, the inheritance of guilt, the shadow of guilt darkening innocent posterity. All of its sins and morbid horrors, its specters, its phantasmas, and even its hellish hopelessness play around his pages, and vanishing between the lines are the less guilty Elves of the Concord Elms, which Thoreau and Old Man Alcott may have felt, but knew not as intimately as Hawthorne. There is often a pervading melancholy about Hawthorne, as Faguet says of de Musset “without posture, without noise but penetrating.” There is at times the mysticism and serenity of the ocean, which Jules Michelet sees in “its horizon rather than in its waters.” There is a sensitiveness to supernatural sound waves. Hawthorne feels the mysteries and tries to paint them rather than explain them — and here, some may say that he is wiser in a more practical way and so more artistic than Emerson. Perhaps so, but no greater in the deeper ranges and profound mysteries of the interrelated worlds of human and spiritual life.

This fundamental part of Hawthorne is not attempted in our music (the 2nd movement of the series) which is but an “extended fragment” trying to suggest some of his wilder, fantastical adventures into the half-childlike, half-fairylike phantasmal realms. It may have something to do with the children's excitement on that “frosty Berkshire morning, and the frost imagery on the enchanted hall window” or something to do with “Feathertop,” the “Scarecrow,” and his “Looking Glass” and the little demons dancing around his pipe bowl; or something to do with the old hymn tune that haunts the church and sings only to those in the churchyard, to protect them from secular noises, as when the circus parade comes down Main Street; or something to do with the concert at the Stamford camp meeting, or the “Slave's Shuffle”; or something to do with the Concord he-nymph, or the “Seven Vagabonds,” or “Circe's Palace,” or something else in the wonderbook — not something that happens, but the way something happens; or something to do with the “Celestial Railroad,” or “Phoebe's Garden,” or something personal, which tries to be “national” suddenly at twilight, and universal suddenly at midnight; or something about the ghost of a man who never lived, or about something that never will happen, or something else that is not.

g

This chapter was taken form Lang’s book

Adventures Among Books.

Andrew Lang, a Scots author and critic

CHAPTER X: NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

Sainte-Beuve says somewhere that it is impossible to speak of “The German Classics.” Perhaps he would not have allowed us to talk of the American classics. American literature is too nearly contemporary. Time has not tried it. But, if America possesses a classic author (and I am not denying that she may have several), that author is decidedly Hawthorne. His renown is unimpeached: his greatness is probably permanent, because he is at once such an original and personal genius, and such a judicious and determined artist.

Hawthorne did not set himself to “compete with life.” He did not make the effort — the proverbially tedious effort — to say everything. To his mind, fiction was not a mirror of commonplace persons, and he was not the analyst of the minutest among their ordinary emotions. Nor did he make a moral, or social, or political purpose the end and aim of his art. Moral as many of his pieces naturally are, we cannot call them didactic. He did not expect, nor intend, to better people by them. He drew the Rev. Arthur Dimmesdale without hoping that his Awful Example would persuade readers to “make a clean breast” of their iniquities and their secrets. It was the moral situation that interested him, not the edifying effect of his picture of that situation upon the minds of novel-readers.

He set himself to write Romance, with a definite idea of what Romance-writing should be; “to dream strange things, and make them look like truth.” Nothing can be more remote from the modern system of reporting commonplace things, in the hope that they will read like truth. As all painters must do, according to good traditions, he selected a subject, and then placed it in a deliberately arranged light — not in the full glare of the noonday sun, and in the disturbances of wind, and weather, and cloud. Moonshine filling a familiar chamber, and making it unfamiliar, moonshine mixed with the “faint ruddiness on walls and ceiling” of fire, was the light, or a clear brown twilight was the light by which he chose to work. So he tells us in the preface to “The Scarlet Letter.” The room could be filled with the ghosts of old dwellers in it; faint, yet distinct, all the life that had passed through it came back, and spoke with him, and inspired him. He kept his eyes on these figures, tangled in some rare knot of Fate, and of Desire: these he painted, not attending much to the bustle of existence that surrounded them, not permitting superfluous elements to mingle with them, and to distract him.

The method of Hawthorne can be more easily traced than that of most artists as great as himself. Pope’s brilliant passages and disconnected trains of thought are explained when we remember that “paper-sparing,” as he says, he wrote two, or four, or six couplets on odd, stray bits of casual writing material. These he had to join together, somehow, and between his “Orient Pearls at Random Strung” there is occasionally “too much string,” as Dickens once said on another opportunity. Hawthorne’s method is revealed in his published note-books. In these he jotted the germ of an idea, the first notion of a singular, perhaps supernatural moral situation. Many of these he never used at all, on others he would dream, and dream, till the persons in the situations became characters, and the thing was evolved into a story. Thus he may have invented such a problem as this: “The effect of a great, sudden sin on a simple and joyous nature,” and thence came all the substance of “The Marble Faun” (“Transformation”). The original and germinal idea would naturally divide itself into another, as the protozoa reproduce themselves. Another idea was the effect of nearness to the great crime on a pure and spotless nature: hence the character of Hilda. In the preface to “The Scarlet Letter,” Hawthorne shows us how he tried, by reflection and dream, to warm the vague persons of the first mere notion or hint into such life as characters in romance inherit. While he was in the Civil Service of his country, in the Custom House at Salem, he could not do this; he needed freedom. He was dismissed by political opponents from office, and instantly he was himself again, and wrote his most popular and, perhaps, his best book. The evolution of his work was from the prime notion (which he confessed that he loved best when “strange”) to the short story, and thence to the full and rounded novel. All his work was leisurely. All his language was picked, though not with affectation. He did not strive to make a style out of the use of odd words, or of familiar words in odd places. Almost always he looked for “a kind of spiritual medium, seen through which” his romances, like the Old Manse in which he dwelt, “had not quite the aspect of belonging to the material world.”

The spiritual medium which he liked, he was partly born into, and partly he created it. The child of a race which came from England, robust and Puritanic, he had in his veins the blood of judges — of those judges who burned witches and persecuted Quakers. His fancy is as much influenced by the old fanciful traditions of Providence, of Witchcraft, of haunting Indian magic, as Scott’s is influenced by legends of foray and feud, by ballad, and song, and old wives’ tales, and records of conspiracies, fire-raisings, tragic love-adventures, and border wars. Like Scott, Hawthorne lived in phantasy — in phantasy which returned to the romantic past, wherein his ancestors had been notable men. It is a commonplace, but an inevitable commonplace, to add that he was filled with the idea of Heredity, with the belief that we are all only new combinations of our fathers that were before us. This has been made into a kind of pseudo-scientific doctrine by M. Zola, in the long series of his Rougon-Macquart novels. Hawthorne treated it with a more delicate and a serener art in “The House of the Seven Gables.”

It is curious to mark Hawthorne’s attempts to break away from himself — from the man that heredity, and circumstance, and the divine gift of genius had made him. He naturally “haunts the mouldering lodges of the past”; but when he came to England (where such lodges are abundant), he was ill-pleased and cross-grained. He knew that a long past, with mysteries, dark places, malisons, curses, historic wrongs, was the proper atmosphere of his art. But a kind of conscientious desire to be something other than himself — something more ordinary and popular — make him thank Heaven that his chosen atmosphere was rare in his native land. He grumbled at it, when he was in the midst of it; he grumbled in England; and how he grumbled in Rome! He permitted the American Eagle to make her nest in his bosom, “with the customary infirmity of temper that characterises this unhappy fowl,” as he says in his essay “The Custom House.” “The general truculency of her attitude” seems to “threaten mischief to the inoffensive community” of Europe, and especially of England and Italy.

Perhaps Hawthorne travelled too late, when his habits were too much fixed. It does not become Englishmen to be angry because a voyager is annoyed at not finding everything familiar and customary in lands which he only visits because they are strange. This is an inconsistency to which English travellers are particularly prone. But it is, in Hawthorne’s case, perhaps, another instance of his conscientious attempts to be, what he was not, very much like other people. His unexpected explosions of Puritanism, perhaps, are caused by the sense of being too much himself. He speaks of “the Squeamish love of the Beautiful” as if the love of the Beautiful were something unworthy of an able-bodied citizen. In some arts, as in painting and sculpture, his taste was very far from being at home, as his Italian journals especially prove. In short, he was an artist in a community for long most inartistic. He could not do what many of us find very difficult — he could not take Beauty with gladness as it comes, neither shrinking from it as immoral, nor getting girlishly drunk upon it, in the æsthetic fashion, and screaming over it in an intoxication of surprise. His tendency was to be rather shy and afraid of Beauty, as a pleasant but not immaculately respectable acquaintance. Or, perhaps, he was merely deferring to Anglo-Saxon public opinion.

Possibly he was trying to wean himself from himself, and from his own genius, when he consorted with odd amateur socialists in farm-work, and when he mixed, at Concord, with the “queer, strangely-dressed, oddly-behaved mortals, most of whom took upon themselves to be important agents of the world’s destiny, yet were simple bores of a very intense water.” They haunted Mr. Emerson as they haunted Shelley, and Hawthorne had to see much of them. But they neither made a convert of him, nor irritated him into resentment. His long-enduring kindness to the unfortunate Miss Delia Bacon, an early believer in the nonsense about Bacon and Shakespeare, was a model of manly and generous conduct. He was, indeed, an admirable character, and his goodness had the bloom on it of a courteous and kindly nature that loved the Muses. But, as one has ventured to hint, the development of his genius and taste was hampered now and then, apparently, by a desire to put himself on the level of the general public, and of their ideas. This, at least, is how one explains to oneself various remarks in his prefaces, journals, and note-books. This may account for the moral allegories which too weirdly haunt some of his short, early pieces. Edgar Poe, in a passage full of very honest and well-chosen praise, found fault with the allegorical business.

Mr. Hutton, from whose “Literary Essays” I borrow Poe’s opinion, says: “Poe boldly asserted that the conspicuously ideal scaffoldings of Hawthorne’s stories were but the monstrous fruits of the bad transcendental atmosphere which he breathed so long.” But I hope this way of putting it is not Poe’s. “Ideal scaffoldings,” are odd enough, but when scaffoldings turn out to be “fruits” of an “atmosphere,” and monstrous fruits of a “bad transcendental atmosphere,” the brain reels in the fumes of mixed metaphors. “Let him mend his pen,” cried Poe, “get a bottle of visible ink, come out from the Old Manse, cut Mr. Alcott,” and, in fact, write about things less impalpable, as Mr. Mallock’s heroine preferred to be loved, “in a more human sort of way.”

Hawthorne’s way was never too ruddily and robustly human. Perhaps, even in “The Scarlet Letter,” we feel too distinctly that certain characters are moral conceptions, not warmed and wakened out of the allegorical into the real. The persons in an allegory may be real enough, as Bunyan has proved by examples. But that culpable clergyman, Mr. Arthur Dimmesdale, with his large, white brow, his melancholy eyes, his hand on his heart, and his general resemblance to the High Church Curate in Thackeray’s “Our Street,” is he real? To me he seems very unworthy to be Hester’s lover, for she is a beautiful woman of flesh and blood. Mr. Dimmesdale was not only immoral; he was unsportsmanlike. He had no more pluck than a church-mouse. His miserable passion was degraded by its brevity; how could he see this woman’s disgrace for seven long years, and never pluck up heart either to share her shame or

peccare forliter

? He is a lay figure, very cleverly, but somewhat conventionally made and painted. The vengeful husband of Hester, Roger Chillingworth, is a Mr. Casaubon stung into jealous anger. But his attitude, watching ever by Dimmesdale, tormenting him, and yet in his confidence, and ever unsuspected, reminds one of a conception dear to Dickens. He uses it in “David Copperfield,” where Mr. Micawber (of all people!) plays this trick on Uriah Heep; he uses it in “Hunted Down”; he was about using it in “Edwin Drood”; he used it (old Martin and Pecksniff) in “Martin Chuzzlewit.” The person of Roger Chillingworth and his conduct are a little too melodramatic for Hawthorne’s genius.

In Dickens’s manner, too, is Hawthorne’s long sarcastic address to Judge Pyncheon (in “The House of the Seven Gables”), as the judge sits dead in his chair, with his watch ticking in his hand. Occasionally a chance remark reminds one of Dickens; this for example: He is talking of large, black old books of divinity, and of their successors, tiny books, Elzevirs perhaps. “These little old volumes impressed me as if they had been intended for very large ones, but had been unfortunately blighted at an early stage of their growth.” This might almost deceive the elect as a piece of the true Boz. Their widely different talents did really intersect each other where the perverse, the grotesque, and the terrible dwell.

To myself “The House of the Seven Gables” has always appeared the most beautiful and attractive of Hawthorne’s novels. He actually gives us a love story, and condescends to a pretty heroine. The curse of “Maule’s Blood” is a good old romantic idea, terribly handled. There is more of lightness, and of a cobwebby dusty humour in Hepzibah Pyncheon, the decayed lady shopkeeper, than Hawthorne commonly cares to display. Do you care for the “first lover,” the Photographer’s Young Man? It may be conventional prejudice, but I seem to see him going about on a tricycle, and I don’t think him the right person for Phoebe. Perhaps it is really the beautiful, gentle, oppressed Clifford who haunts one’s memory most, a kind of tragic and thwarted Harold Skimpole. “How pleasant, how delightful,” he murmured, but not as if addressing any one. “Will it last? How balmy the atmosphere through that open window! An open window! How beautiful that play of sunshine. Those flowers, how very fragrant! That young girl’s face, how cheerful, how blooming. A flower with the dew on it, and sunbeams in the dewdrops . . . “ This comparison with Skimpole may sound like an unkind criticism of Clifford’s character and place in the story — it is only a chance note of a chance resemblance.

Indeed, it may be that Hawthorne himself was aware of the resemblance. “An individual of Clifford’s character,” he remarks, “can always be pricked more acutely through his sense of the beautiful and harmonious than through his heart.” And he suggests that, if Clifford had not been so long in prison, his æsthetic zeal “might have eaten out or filed away his affections.” This was what befell Harold Skimpole — himself “in prisons often” — at Coavinses! The Judge Pyncheon of the tale is also a masterly study of swaggering black-hearted respectability, and then, in addition to all the poetry of his style, and the charm of his haunted air, Hawthorne favours us with a brave conclusion of the good sort, the old sort. They come into money, they marry, they are happy ever after. This is doing things handsomely, though some of our modern novelists think it coarse and degrading. Hawthorne did not think so, and they are not exactly better artists than Hawthorne.