Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) (180 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Illustrated) Online

Authors: NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

“Why hast thou spilt the drink?” said Septimius, bending his dark brows upon her, and frowning over her. “We might have died together.”

“No, live, Septimius,” said the girl, whose face appeared to grow bright and joyous, as if the drink of death exhilarated her like an intoxicating fluid. “I would not let you have it, not one drop. But to think,” and here she laughed, “what a penance,–what months of wearisome labor thou hast had,–and what thoughts, what dreams, and how I laughed in my sleeve at them all the time! Ha, ha, ha! Then thou didst plan out future ages, and talk poetry and prose to me. Did I not take it very demurely, and answer thee in the same style? and so thou didst love me, and kindly didst wish to take me with thee in thy immortality. O Septimius, I should have liked it well! Yes, latterly, only, I knew how the case stood. Oh, how I surrounded thee with dreams, and instead of giving thee immortal life, so kneaded up the little life allotted thee with dreams and vaporing stuff, that thou didst not really live even that. Ah, it was a pleasant pastime, and pleasant is now the end of it. Kiss me, thou poor Septimius, one kiss!”

[

She gives the ridiculous aspect to his scheme, in an airy way

.]

But as Septimius, who seemed stunned, instinctively bent forward to obey her, she drew back. “No, there shall be no kiss! There may a little poison linger on my lips. Farewell! Dost thou mean still to seek for thy liquor of immortality?–ah, ah! It was a good jest. We will laugh at it when we meet in the other world.”

And here poor Sibyl Dacy's laugh grew fainter, and dying away, she seemed to die with it; for there she was, with that mirthful, half-malign expression still on her face, but motionless; so that however long Septimius's life was likely to be, whether a few years or many centuries, he would still have her image in his memory so. And here she lay among his broken hopes, now shattered as completely as the goblet which held his draught, and as incapable of being formed again.

The next day, as Septimius did not appear, there was research for him on the part of Doctor Portsoaken. His room was found empty, the bed untouched. Then they sought him on his favorite hill-top; but neither was he found there, although something was found that added to the wonder and alarm of his disappearance. It was the cold form of Sibyl Dacy, which was extended on the hillock so often mentioned, with her arms thrown over it; but, looking in the dead face, the beholders were astonished to see a certain malign and mirthful expression, as if some airy part had been played out,–some surprise, some practical joke of a peculiarly airy kind had burst with fairy shoots of fire among the company.

“Ah, she is dead! Poor Sibyl Dacy!” exclaimed Doctor Portsoaken. “Her scheme, then, has turned out amiss.”

This exclamation seemed to imply some knowledge of the mystery; and it so impressed the auditors, among whom was Robert Hagburn, that they thought it not inexpedient to have an investigation; so the learned doctor was not uncivilly taken into custody and examined. Several interesting particulars, some of which throw a certain degree of light on our narrative, were discovered. For instance, that Sibyl Dacy, who was a niece of the doctor, had been beguiled from her home and led over the sea by Cyril Norton, and that the doctor, arriving in Boston with another regiment, had found her there, after her lover's death. Here there was some discrepancy or darkness in the doctor's narrative. He appeared to have consented to, or instigated (for it was not quite evident how far his concurrence had gone) this poor girl's scheme of going and brooding over her lover's grave, and living in close contiguity with the man who had slain him. The doctor had not much to say for himself on this point; but there was found reason to believe that he was acting in the interest of some English claimant of a great estate that was left without an apparent heir by the death of Cyril Norton, and there was even a suspicion that he, with his fantastic science and antiquated empiricism, had been at the bottom of the scheme of poisoning, which was so strangely intertwined with Septimius's notion, in which he went so nearly crazed, of a drink of immortality. It was observable, however, that the doctor–such a humbug in scientific matters, that he had perhaps bewildered himself–seemed to have a sort of faith in the efficacy of the recipe which had so strangely come to light, provided the true flower could be discovered; but that flower, according to Doctor Portsoaken, had not been seen on earth for many centuries, and was banished probably forever. The flower, or fungus, which Septimius had mistaken for it, was a sort of earthly or devilish counterpart of it, and was greatly in request among the old poisoners for its admirable uses in their art. In fine, no tangible evidence being found against the worthy doctor, he was permitted to depart, and disappeared from the neighborhood, to the scandal of many people, unhanged; leaving behind him few available effects beyond the web and empty skin of an enormous spider.

As to Septimius, he returned no more to his cottage by the wayside, and none undertook to tell what had become of him; crushed and annihilated, as it were, by the failure of his magnificent and most absurd dreams. Rumors there have been, however, at various times, that there had appeared an American claimant, who had made out his right to the great estate of Smithell's Hall, and had dwelt there, and left posterity, and that in the subsequent generation an ancient baronial title had been revived in favor of the son and heir of the American. Whether this was our Septimius, I cannot tell; but I should be rather sorry to believe that after such splendid schemes as he had entertained, he should have been content to settle down into the fat substance and reality of English life, and die in his due time, and be buried like any other man.

A few years ago, while in England, I visited Smithell's Hall, and was entertained there, not knowing at the time that I could claim its owner as my countryman by descent; though, as I now remember, I was struck by the thin, sallow, American cast of his face, and the lithe slenderness of his figure, and seem now (but this may be my fancy) to recollect a certain Indian glitter of the eye and cast of feature.

As for the Bloody Footstep, I saw it with my own eyes, and will venture to suggest that it was a mere natural reddish stain in the stone, converted by superstition into a Bloody Footstep.

A ROMANCE

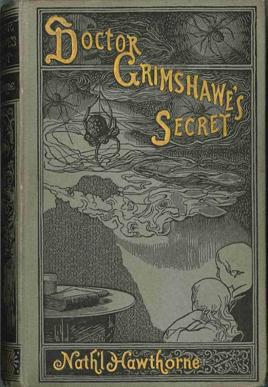

Hawthorne began this unfinished novel in 1861 and it was published posthumously in 1883, by his son, Julian.

Doctor Grimshawe’s Secret

contains much autobiographical material, with one of the principal topics being Hawthorne’s unresolved feelings about his childhood guardian, whose character is represented as Dr. Grimshawe, a spider-cultivating eccentric. The central motif , the “secret”, of the novel is an all-encompassing spider web.

The first edition

CONTENTS