Read Dewey's Nine Lives Online

Authors: Vicki Myron

Dewey's Nine Lives (6 page)

She held Tobi in her arms. She stroked her as Dr. Esterly prepared the needle. The cat laid her head against Yvonne’s elbow and closed her eyes, as if she felt safe and comfortable with her friend. When she felt the prick, Tobi let out a terrible yowl, but she didn’t bolt. She simply looked up into Yvonne’s face, terrified, wondering, then slumped over and slipped away. Yvonne, with the help of her father, buried her in a far corner of their backyard.

She had so many happy memories. The Christmas tree. The spinning chair. The nights together in bed. But that last yowl, a sound unlike any Tobi had ever made . . . it was something Yvonne could not forget. It tore her, and a great rush of guilt came flooding out. Tobi dedicated her life to Yvonne, but in her last years, when Tobi was old and sick and needed her most, Yvonne felt she had turned away. She hadn’t spun her in the swivel chair; she hadn’t built Christmas present tunnels; she hadn’t noticed how sick Tobi was getting.

That night, she went to prayer meeting. Her eyes were puffy and red, and the tears were still on her cheeks. Her fellow worshippers kept asking, “Are you okay, Yvonne? What’s the matter?”

“My cat died today,” she told them.

“Oh, I’m so sorry,” they said, patting her on the arm. Then, with nothing more to say, they walked away. They meant well, Yvonne knew. They were good people. But they didn’t understand. To them, it was just a cat. Like the rest of us, they didn’t even know Tobi’s name.

The next day, when she visited the Spencer Public Library, Yvonne didn’t feel any better. In fact, she felt worse. More guilty. More alone. She had no desire, she realized, to even browse the library books. Instead, she went straight to a chair, sat down, and thought about Tobi.

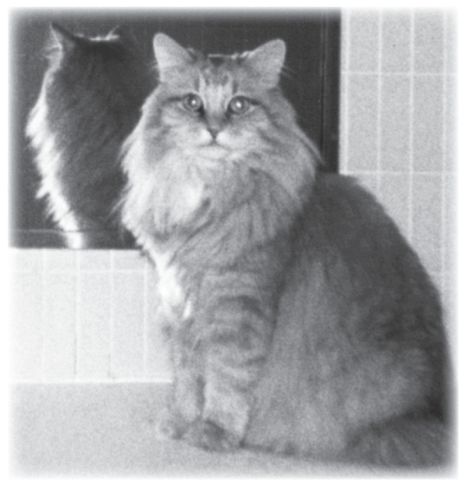

A minute later, Dewey came around the corner and walked slowly toward her. Every time he had seen her, for at least the last few years, Dewey had meowed and run to the women’s bathroom door. Yvonne would open the door, and Dewey would jump on the sink and meow until she turned on the water. After staring at the column of water for half a minute, he’d bat it with his paw, jump back in shock, then creep forward and repeat the process again. And again. And again. It was their special game, a ritual that had developed over a hundred mornings spent together. And Dewey did it every single time.

But not this time. This time, Dewey stopped, cocked his head, and stared at her. Then he sprang into her lap, nuzzled her softly with his head, and curled up in her arms. She stroked him gently, occasionally wiping away a tear, until his breathing became gentle and relaxed. Within minutes, he was asleep.

She kept petting him, slowly and gently. After a while, the weight of her sadness seemed to lighten, and then lift, until, finally, it felt as if it were floating away. It wasn’t just that Dewey realized how much she hurt. It wasn’t just that he knew her, or that he was a friend. As she watched Dewey sleeping, she felt her guilt disappear. She had done her best for Tobi, she realized. She had loved her little cat. She wasn’t required to spend every minute proving that. There was nothing wrong with having a life of her own. It was time, for both of their sakes, to let Tobi go.

My friend Bret Witter, who helps me with these books, has a pet peeve (pun intended). He hates when people ask him, “So why was Dewey so special?”

“Vicki spent two hundred eighty-eight pages trying to explain that,” he says. “If I could summarize it for you in a sentence, she would have written a greeting card instead.”

He thought that was clever. Then he realized the question always made him think of something that happened in his own life, something that didn’t involve cats or libraries or even Iowa but that might provide a short answer nonetheless. So he’d crack about the greeting card, then tell a story about growing up with a severely mentally and physically handicapped kid in his hometown of Huntsville, Alabama. The boy went to his school and his church, so by the time the incident happened in seventh grade, Bret had spent time with him six days a week, nine months a year, for seven years. In that whole time, the boy, who was too handicapped to speak, had never gotten emotional, never expressed happiness or frustration, never brought attention to himself in any way.

Then one day, in the middle of Sunday school, he started screaming. He pushed over a chair, picked up a container of pencils, and, with an exaggerated motion, began throwing them wildly around the room. The other kids sat at the table, staring. The Sunday school teacher, after some initial hesitation, began yelling at him to settle down, to be careful, to stop disrupting the class. The boy kept screaming. The teacher was about to throw him out of the room when, all of a sudden, a kid named Tim stood up, walked over, put his arm around the boy “like he was a human being,” as Bret always tells it, and said, “It’s all right, Kyle. Everything is okay.”

And Kyle calmed down. He stopped flailing, dropped the pencils, and started crying. And Bret thought,

I wish I had done that

.

I wish I had understood what Kyle needed.

I wish I had done that

.

I wish I had understood what Kyle needed.

That’s Dewey. He always seemed to understand, and he always knew what to do. I’m not suggesting Dewey was the same as the boy who reached out—Dewey was a cat, after all—but he had an empathy that was rare. He sensed the moment, and he responded. That’s what makes people, and animals, special. Seeing. Caring. Loving. Doing.

It’s not easy. Most of the time, we are so busy and distracted that we don’t even realize we missed the opportunity. I can look back now and see that the first ritual Yvonne developed with Dewey, before the bathroom-water-swatting, was catnip. Every day, she clipped fresh catnip out of her yard and placed it on the library carpet. Dewey always rushed over to sniff it. After a few deep snorts, he plowed his head into it, chewing wildly, his mouth flapping and his tongue lapping at the air. He rubbed his back on the floor so the little green leaves stuck in his fur. He rolled onto his stomach and pushed his chin against the carpet, slithering like the Grinch stealing Christmas presents. Yvonne always knelt beside him, laughing and whispering, “You really love that catnip, Dewey. You really love that catnip, don’t you?” as he flailed his legs in a series of wild kicks until, finally, he collapsed exhausted onto the floor, his legs spread out in every direction and his belly pointed toward the sky.

Then one day, with Dewey in full catnip conniption (the library staff called it the Dewey Mambo), Yvonne looked up and saw me staring at her. I didn’t say anything, but a few days later, I stopped her and said, “Yvonne, please don’t bring Dewey so much catnip. I know he enjoys it, but it’s not good for him.”

She didn’t say anything. She just looked down and walked away. I only meant for her to cut her gift back to, for instance, once a week, but she never brought another leaf of catnip to the library.

At the time, I thought I was doing the right thing, because that catnip was wearing Dewey out. He would go absolutely bonkers for twenty minutes, then Yvonne would leave and Dewey would pass out for hours. That cat was catatonic. It didn’t seem fair. Yvonne was enjoying Dewey’s company, but his other friends weren’t getting a chance.

In hindsight, I should have been more delicate in handling the catnip incident. I should have understood that this wasn’t just a habit for Yvonne, it was an important part of her day. Instead of examining the root of the behavior, I looked at the outward actions and told her to stop. Instead of putting my arm around her, I pushed her away.

But Dewey—he never did that. A thousand times, in a thousand different ways, Dewey was there when people needed him. He did it for dozens of people, I’m sure, who have never opened up to me. He did it for Bill Mullenburg, and he did it for Yvonne, exactly as Tim had done it with Kyle in Bret’s Sunday school class. When no one else understood, Dewey made the gesture. He didn’t understand the root causes, of course, but he sensed something was wrong. And out of animal instinct, he acted. In his own way, Dewey put his arm around Yvonne and said,

It’s all right. You are one of us. You will be fine.

It’s all right. You are one of us. You will be fine.

I’m not saying Dewey changed Yvonne’s life. I think he eased her sorrow, but he by no means ended it. A month after Tobi’s passing, Yvonne lost her temper on the assembly line and was not only fired but escorted out of the building. She had been frustrated by management for a long time, but I can’t help but believe the last straw was the pain of Tobi’s death.

It didn’t stop there. A few years later, her mother died of colon cancer. Two years after that, Yvonne was diagnosed with uterine cancer. She drove six hours to Iowa City, for six months, to receive treatment. By the time she beat the cancer, her legs had given way. She had stood in the same position on the assembly line eight hours a day, five days a week, for years, and the effort had worn down her knees.

But she still had her faith. She still had her routines. And she still had Dewey. He lived fifteen years after Tobi’s death, and for all those years, Yvonne Barry came to the library several times each week to see him. If you had asked me at the time, I would not have said their relationship was particularly special. Many people came into the library every week, and almost all of them stopped to visit with Dewey. How was I to know the difference between those who thought Dewey was cute, and those who needed and valued his friendship and love?

After Dewey’s memorial service, Yvonne told me about the day Dewey sat on her lap and comforted her. It still meant something to her, more than a decade later. And I was touched. Until that moment, I didn’t know Yvonne had ever had a cat of her own. I didn’t know what Tobi meant to her, but I knew Dewey had comforted her, as he had always comforted me, simply by being present in her life. Little moments can mean everything. They can change a life. Dewey taught me that. Yvonne’s story (once I took the time to listen) confirmed it. That moment on her lap epitomized Dewey’s understanding and friendship, his effect on the people of Spencer, Iowa, in a way I had never considered before.

I didn’t notice when Yvonne stopped coming to the library after Dewey’s death. I knew her visits had become less frequent, but she disappeared just as she appeared: like a shadow, without a sound. By the time I went to visit her two years after Dewey’s death, she was living in a rehabilitation facility with a brace on her right leg. She was only in her fifties, but the doctors weren’t sure she would walk again. Even if she recovered, she had no place to go. Her father was in the nursing home next door, and the family house had been sold. Yvonne told the new owners, “Don’t dig down in that corner of the yard because that’s where my Tobi is buried.”

“Tobi’s still down there,” she told me. “At least her body anyway.”

There was a Bible on her nightstand and a scripture taped to her wall. Her father was in Yvonne’s room in a wheelchair, a frail old man who had lost his ability to hear and see. She introduced us, but beyond that, Yvonne hardly seemed to notice he was there. Instead, she showed me a small figurine of a Siamese cat, which she kept on a tray beside her bed. Her aunt Marge had given it to her, in honor of Tobi. No, she didn’t have any photographs of Tobi to share. Her sister had put all of Yvonne’s belongings into storage, and she didn’t have the key. If I needed a photograph, she said, there was always the one of her and Dewey, taken at the library party twenty years before. Someone, somewhere, probably had a copy.

When I asked her about Dewey, she smiled. She told me about the women’s bathroom, and his birthday party, and finally about the afternoon he spent on her lap. Then she looked down and shook her head sadly.

“I went to the library several times to see his grave,” she said. “I’ve been inside. I looked around. It just doesn’t seem the same. No Dewey. I mean, I saw the statue of him and I thought,

That’s nice, it looks just like Dewey

, but it wasn’t like Dewey was really there.

That’s nice, it looks just like Dewey

, but it wasn’t like Dewey was really there.

“I don’t go to that place anymore. It was that cat, you know. Dewey, he’d always be there. Even if he was hiding somewhere, I’d just say to myself, ‘Well, I’ll see him next time.’ But then I went and no Dewey. I looked at the place where he used to sit and it was empty and I thought,

Well, nothing to do here

. It just feels like a building with books in it now.”

Well, nothing to do here

. It just feels like a building with books in it now.”

I wanted to ask her more, to figure something out, to learn something profound about cats and libraries and the crosscurrents of loneliness and love underneath the surface of even the most peaceful towns and the most peaceful lives. I wanted to know her because, in the end, it felt as if she was barely present in her own story.

But Yvonne just smiled. Was she thinking of that moment with Dewey on her lap? Or was she thinking of something else, something deeper that she would never share, and that only she would ever understand?

“He was my Dewey Boy.” That’s all she said. “Big Dew.”

TWO

Mr. Sir Bob Kittens (aka Ninja, aka Mr. Pumpkin Pants)

Other books

Landline by Rainbow Rowell

Falling for Him 4 (Rachel and Peter in Love) by Gray, Jessica

The Roommate by Carla Krae

In the Suicide Mountains by John Gardner

Lost Girls by Ann Kelley

The Arranged Marriage by Emma Darcy

That Magic Mischief by Susan Conley

Deadly Target [IAD Agency 3] (Siren Publishing Classic) by Roma, Laurie

Cause of Death (Det. Annie Avants Book 1) by Renee Benzaim

Undraland by Mary Twomey