Diamond in the Rough (24 page)

Read Diamond in the Rough Online

Authors: Shawn Colvin

1996

(Photograph courtesy of Tracie Goudi)

All through the night I can pretend

The morning will make me whole again.

And every day I can begin

To wait for the night again.

I guess I knew it was bad before I really said anything to the doctor. It had happened before, feeling bad but not wanting to admit it. I wanted it not to be true. When you’re depressed, you don’t feel like bothering about anything anyway—brushing your teeth and bathing are monumental tasks—and you have no perspective with which to gauge the worsening of your condition. You learn to look at the usual benchmarks: how you eat and sleep, if you’re caring about your hygiene, if anything interests you besides sitting in a corner, and how elaborate or specific your suicidal thoughts are. And then there is the loathsome necessity of calling the doctor. Again.

The Prozac I’d been taking for eighteen years was no longer working, and my new doctor put me on Cymbalta. I gave it the requisite three weeks allotted for the drug to take effect, but nothing remarkable happened. So she, the doctor, raised the dosage. I waited again, this time longer, and still I was flat and disconnected and anxious and paralyzed. I went to see her again, ready to admit I wasn’t getting better, as though it were my fault. That’s what depressed people do. They think everything is their fault, especially the depression. Unfortunately, a lot of psychopharmacologists, like many doctors, are egomaniacs with lousy bedside manners, and inevitably I would reach a point of diminishing returns with them, either because they ran out of ideas or said something stupid. This doctor fell into both categories. I went in, lower than whale shit, with the disappointing news. I went in because I had to believe there was something else we could try and I needed her expertise to guide me there. The Cymbalta wasn’t working, I told her. We needed a new strategy.

She looked at me, cocked her head to one side, and said brightly, “You know what I want you to do?” She said, “I want you to go home and watch comedies. I want you to find something, maybe on YouTube, that really, really cracks you up.”

Are you kidding me? How do I explain what a ludicrous suggestion this is? We’re talking clinical depression here, clinical depression that I’d been diagnosed with and treated for since I was nineteen years old. It’s an illness. And her best idea was to try to make me laugh? That’s like suggesting a Band-Aid for a long, deep gash. No, it’s worse than that. It’s like asking a blind person to see. I paid the $175 fee for that gem of a suggestion and stumbled out the door. Another one bites the dust. She basically told me to snap out of it, by far the

dumbest

thing you can say to somebody who’s depressed.

I got in touch with a big-shot doctor in New York. He thought since Elavil had worked for me when I was nineteen, we should try it again. But first I had to quit the Cymbalta, and he said—and I quote—“Cymbalta is a bitch to get off of.” To get off Cymbalta as safely as possible, I had to start taking … Prozac.

This would put us at about March of 2009. My relationship ended in January 2008, over a year prior. It was impossible to tell at this point where the emotional fallout from that ended and the clinical depression began. I had certainly been depressed before and had been dumped before, too, but this time the convergence of chemistry and situation made for a sort of sinister alchemy. I can say with certainty that I’d been sliding downhill since even before the breakup. I was jumpy and massively oversensitive. I cried because I didn’t have the right jacket. I cried because we were driving on a curvy road. I cried because of the way the sun was shining. I cried because a car honked its horn. I was crying because I was depressed.

Then the breakup. I admitted myself to a psychiatric facility in Austin at some point in the spring of 2008, because I was unable to do anything but cry. I stayed for a few hours, until I realized I was more comfortable crying at home. I got in a long nap, had some bad food, and called my mother for a ride. Oh, well. I’d always wanted to know what the nuthouse was like, just in case. Now I knew. I fired the comedy doctor, and the big-shot New York doctor came into play. It was during a music cruise, in February 2009, that I started the process of getting off Cymbalta. I had begun the taper two days before the cruise, and by the second day on the boat I was basically not functioning. I would wake up, if I slept, to a depression so profound and paralyzing and frightening that it required two or three milligrams of Ativan to deliver relief by knocking me out. By evening I was able to do a show. I don’t remember the shows, but I’ve been told I was not up to par, which hardly surprises me. I remember sinking into blackness within two hours of waking, crying uncontrollably, taking the Ativan, and shuffling around the deck until I knew I could sleep. Then I’d stay in bed until it got dark.

When we reached dry land after a week, I consulted the big shot. He added nortriptyline. I started having massive anxiety attacks. He concluded I was in a “mixed state,” meaning a state of mania and depression concurrently. He scrapped the nortriptyline and added Depakote to control the mania. No change. A month went by, in which I did nothing but cry. The month of March 2009. Of course I thought of suicide, but I couldn’t do that to my daughter.

My mother helped me in countless ways during all this, mostly to pinch-hit for me with Callie, getting her fed, entertaining her. I called her in the middle of the night on many, many occasions in the midst of an anxiety attack, and she would get up and drive to my house to be with me just as many times. I believe she would have done anything in her power to help me.

I got another doctor, this time in Austin. Dr. Lynn Spillar. She took me off Depakote, raised the Prozac dosage, reintroduced Abilify, and had me take Lunesta to get my sleep pattern back to normal. Very slowly I noticed I wasn’t crying all the time and that I could function, however minimally, but I never fully recovered; there was a piece of me missing. I

could

function, but only at the most base level. I was flat and disconnected and anxious and full of dread, scared to drive, scared to fly, scared to perform, scared to leave the house. This is when, at Dr. Spillar’s suggestion, I called Sheppard Pratt, a psychiatric inpatient facility in Baltimore, to see if they had a bed for me. She also asked me to make an appointment with a doctor in Austin who administered ECT, electroconvulsive therapy. The meds weren’t cutting it, that was that. Time for the big guns.

Dr. Spillar had one more idea before we tried ECT, and I thought it was a terrible one. She wanted me to try a stimulant. I’d all my life had panic attacks, and even a cup of coffee could put me over the edge. I was a drunk; I liked downers. A stimulant seemed counterintuitive, but I was at the point where I certainly had nothing to lose. It was November 9, 2009. Callie was scheduled to spend the weekend with her father, and I knew I couldn’t stand being in my house alone for three days. I got online and booked a Southwest flight to Providence, Rhode Island, by way of Baltimore, to see Carolyn.

Carolyn Rosenfeld is my guardian angel. Look up “selfless” in the dictionary, you will find her name. When we met eighteen years ago, she handled corporate accounts for a graphics company in Providence, but, loving music as she does, she also did favors here and there for a great club called Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel—things like picking up artists from the airport. That’s how I met her. Bit by bit over the years, I’ve worn her down and now she works for me for a tenth of what she used to make, and for twice the effort. Carolyn travels with me. Carolyn was on the boat trip. She walked me around the deck, put me to bed, got me up. Carolyn is my friend. She is my child’s godmother. It was Carolyn who stayed with me in Austin for an entire month while I was having what can only be called a nervous breakdown.

Me and Carolyn Rosenfeld, 2010

(Photograph courtesy of Lisa Arzt)

I filled the script for the stimulant Concerta, normally used as an ADD drug. I threw it in my bag, determined to try it, but only once I was with Carolyn, so she could talk me down when I started to trip on this shit. I got to the airport in Austin, and it was the oddest thing—I boarded the plane, and there in an aisle seat was Dr. Lynn Spillar. She was attending a conference in Baltimore. I took the window seat beside her. I have to say this is one of the times in my life where I believe absolutely that I was witnessing a higher power in action. Truly, it was in my face, it was a sign. I couldn’t have felt safer if it had been Mother Teresa in that aisle seat. We didn’t talk much, but it didn’t matter. I got to Providence. It was Friday. I got up Saturday morning, took that damn pill, and set out for the mall. When in doubt, shop, that is my motto.

I felt better inside of two hours.

I felt better. Something clicked. I had that elusive, intangible something back—I felt like me. I could relax, I could laugh, I could think. I wasn’t just waiting to die anymore. There was the possibility of life being

positive.

The ex receded in my mind, became abstract, a phantom insect I could swat away. I wanted to cook dinner, I wanted to have conversations, I wanted to hear music. I swear, it was a miracle. I was

back.

Dr. Spillar was on the same plane home to Austin from Baltimore on Sunday. I told her what had happened. “You needed dopamine,” she said. Dopamine regulates one’s sense of pleasure. Jesus H. God.

I looked over my shoulder for months, but it held, this cocktail of Prozac, Abilify, and Concerta. I told Spillar that the stimulant was the magic bullet. She stood up for the other two drugs, saying that for whatever reason there was a harmonic convergence among all three. While all of them may have played a part in leveling my depression, Concerta was the superhero that kicked its ass and took its name.

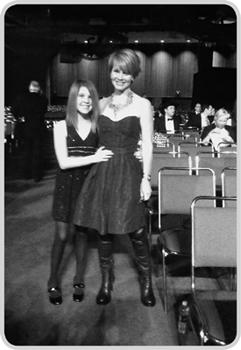

Me and Callie at the Grammys, 2010

(Photograph courtesy of Carolyn Rosenfeld)

Singing back home to you,

Laughing back home to you,

Dragging back home to you.

I have two homes. One is in Austin, Texas. It’s eclectically chaotic. It’s colorful. The living-room walls are Brigade (a deep marine blue), the kitchen cabinets are Fig (chartreuse), the office is Flower Pot. For my bedroom I went with wallpaper called Chiang Mai Dragon by Schumacher in the mocha colorway. Very strong choice. I live with my daughter. This summer, at the age of twelve, Callie decided not to go on the road with me for the first time. She’s starting to make her own life, just as I did. I still talk to my friends from junior high school—Janey, Liz, Mandy, Joanne, and Todd. That’s what I wish for Callie, that she’ll have the kind of friends I do. She picked out the color for her own room. It’s Venetian Blue.

My other home is with all of you.

Whether it’s been in vans or buses, or limos or airplanes, I’ve spent much of the last thirty-five years on tour. It’s been my privilege to be wanted and to give what I truly love to give for all this time. I always wanted to play music, my whole life. My audience allows me to, and it’s an honor. I’ve played festivals, amphitheaters, state fairs, countless clubs and theaters in every single state in the Union (including Alaska and Hawaii). I’ve played the Dead Sea, Europe, China, Australia, and New Zealand. Even Carnegie Hall.

And over the years I’ve been lucky enough to get the opportunity to meet and sometimes to perform with many of my heroes and colleagues. Now, bear with me. It’s a long list. But this South Dakota geek of a girl still cannot believe it. So here goes: Sting, Lyle Lovett, Jackson Browne, John Hiatt, Bruce Hornsby, Bonnie Raitt, David Crosby, Graham Nash, Neil Young, Paul Simon, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Jane Siberry, Victoria Williams, Elton John, Bernie Taupin, Paul McCartney, Neil Finn, the Band, Chris Whitley, Jesse Winchester, Chris Hillman, Stephen Stills, Odetta, Judy Collins, Rosanne Cash, Rodney Crowell, Bob Dylan, Elvis Costello, Chrissie Hynde, Roger Daltrey, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen, Carole King, the Eagles, Ringo, Eric Idle, Stevie Nicks, Sheryl Crow, David Gray, Chris Isaak, Richard Thompson, Loudon Wainwright, Emmylou Harris, Patty Griffin, Alison Krauss, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Dar Williams, the Cowboy Junkies, the Indigo Girls, Tony Bennett, Neil Finn, Sarah McLachlan, Brandi Carlile, Steve Earle, Paula Cole, Jason Mraz—even ’N Sync, Bill Clinton, Ernie from

Sesame Street,

and Spinal Tap. Blessed!