Did Muhammad Exist?: An Inquiry into Islam's Obscure Origins (26 page)

Read Did Muhammad Exist?: An Inquiry into Islam's Obscure Origins Online

Authors: Robert Spencer

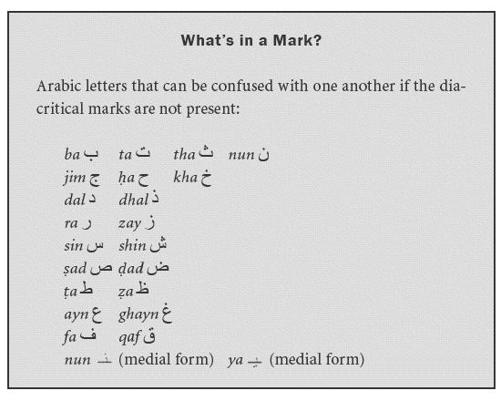

As such, diacritical marks are essential to being able to make sense of the Qur'an or any other Arabic text. Unfortunately, the earliest manuscripts of the Qur'an do not contain most diacritical marks. A scholar of hadiths named Abu Nasr Yahya ibn Abi Kathir al-Yamami (d. 749) recalled: “The Qur'an was kept free [of diacritical marks] in

mushaf

[the original copies]. The first thing people have introduced in it is the dotting at the letter

ba

( ) and the letter

) and the letter

ta

( ), maintaining that there is no sin in this, for this illuminates the Qur'an.”

), maintaining that there is no sin in this, for this illuminates the Qur'an.”

5

Abu Nasr did not say when these marks began to be introduced, but the fragments of Qur'anic manuscripts that many scholars date to the first century of the Arabian conquests have only rudimentary diacritical marks. Some manuscripts distinguish one set of identical letters from another—

ta

( ) from (

) from (

ba

( ), or

), or

fa

( ) from

) from

qaf

( )—but they

)—but they

leave the other sets of identical letters indistinguishable. Nor are all the earliest manuscripts consistent in the sets of identical letters they choose to distinguish from one another.

6

An Islamic scholar writing late in the tenth century recounted a story in which the confusion of two sets of letters—

zay

( ) for

) for

ra

( ), and

), and

ta

( ) for

) for

ba

( )—came into play. A young man named Hamza began reciting the Qur'an's second sura, which begins, “This is the Book with no doubt in it” (2:2). “No doubt in it” in Arabic is

)—came into play. A young man named Hamza began reciting the Qur'an's second sura, which begins, “This is the Book with no doubt in it” (2:2). “No doubt in it” in Arabic is

la raiba fihi

, but this unfortunate young man read out

la zaita fihi

, or “no oil in it,” so that the book, instead of being beyond question, was oil-free. (Hamza was thereafter known as

az-Zayyat

, or “the dealer in oil.”)

Hamza may simply have slipped up or been making a joke. But because the earliest extant manuscripts of the Qur'an contain none of the marks that would have enabled him to distinguish a

ra

from a

zay

and a

ba

from a

ta

, it is entirely possible that he was doing the best he could with a highly ambiguous text.

The implications of this confusion are enormous. Hamza's error could have been committed even by those Islamic scholars who added in the diacritical marks that now form the canonical text of the Qur'an. It is entirely possible that what is taken for one word in that canonical text may originally have been another word altogether.

Diacritical marks may have been purposefully omitted. The Qur'an begins, after all, by proclaiming itself to be “a guidance unto those who ward off evil” (2:2); it may be that that guidance was a secret given only to the initiated. If the Qur'an's instructions were to be denied anyone outside a select circle, it would explain why there is virtually no mention of the Qur'an, much less quotation of it, in the coinage and inscriptions of the Arabian conquerors. Even as the conquerors grew entrenched, some saw the introduction of diacritical marks and vowel points as an unlawful

bida

, “innovation.” Hence the caliph al-Mamun (813–833) forbade either one to be introduced into the Qur'anic text, confusion be damned.

7