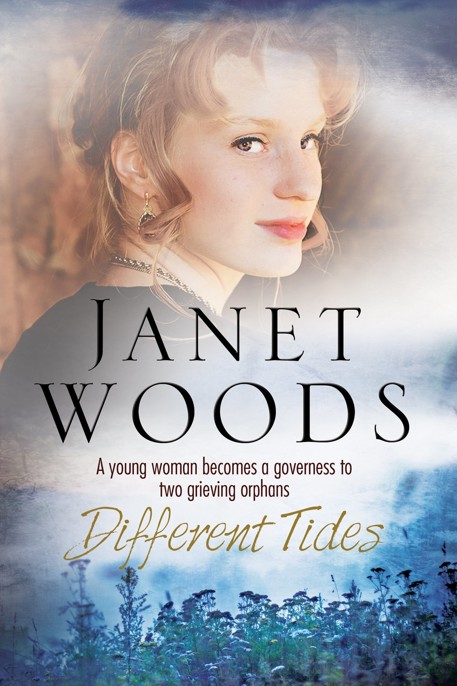

Different Tides

Authors: Janet Woods

Table of Contents

Recent Titles by Janet Woods from Severn House

AMARANTH MOON

BROKEN JOURNEY

CINNAMON SKY

THE COAL GATHERER

DIFFERENT TIDES

EDGE OF REGRET

HEARTS OF GOLD

LADY LIGHTFINGERS

I’LL GET BY

MOON CUTTERS

MORE THAN A PROMISE

PAPER DOLL

SALTING THE WOUND

SECRETS AND LIES

THE STONECUTTER’S DAUGHTER

STRAW IN THE WIND

TALL POPPIES

WITHOUT REPROACH

Janet Woods

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

First published in Great Britain and the USA 2014 by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD of

19 Cedar Road, Sutton, Surrey, England, SM2 5DA.

eBook edition first published in 2014 by Severn House Digital

an imprint of Severn House Publishers Limited

Copyright © 2014 by Janet Woods.

The right of Janet Woods to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Woods, Janet, 1939 – author.

Different Tides.

1. Governesses–Fiction. 2. Orphans–Fiction. 3. Dorset

(England)–Fiction. 4. Great Britain–History–William

IV, 1830-1837–Fiction. 5. Love stories.

I. Title

823.9’14-dc23

ISBN-13: 978-0-7278-8401-5 (cased)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78010-550-5 (ePub)

Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

This ebook produced by

Palimpsest Book Production Limited,

Falkirk, Stirlingshire, Scotland

Clementine, 1835

Despite having been orphaned for several years, Clementine could still remember some details of her parents.

‘My father’s name was Howard Morris. He was an army officer and died at the battle of Waterloo. He was a hero. I was young when he died so I can’t recall ever meeting him.’

The man questioning her was in his fifties, she imagined. He’d described his occupation as a lawyer and investor, and his name was John Beck. He looked down his nose at her with a faintly quizzical smile but she didn’t feel intimidated since nature had provided him with a nose that was long. His eyes were kind.

‘Quite. Now … do tell me about your mother, young lady.’

‘Her name was Hannah Cleaver. She was not very strong and she died.’ Clementine didn’t like talking about her mother. She fell silent.

He waited a short while for her to continue. When no more information was forthcoming he looked at her. ‘Can you tell us what your mother’s occupation was?’

‘She sang, I think. I only remember seeing her once after I was left at the school. I was about ten then. She looked ill. She said I’d have to earn my living when I grew up, so I should work hard and acquire the skills required to be a governess because it was a respectable occupation. She told me that both she and my father wanted that. A month later they told me she’d died in the workhouse.’

‘That must have been a shock. Where did you live before you were accepted into the school?’

‘There was no one close left on my mother’s side, so we moved in with a distant relative of my father in Portland. My mother became his housekeeper. He was a minister in the church there.’

Clementine grimaced as she recalled an old man with a bald patch on his head – a man who had cuddled her and kissed her on the mouth when her mother wasn’t there, and then kissed and cuddled her mother when she was there. His breath had been unpleasant, as if an attempt had been made to disguise its stink with peppermint. It had been their secret, he’d said, and she would be taken away from her mother if she told anyone. In her innocence she’d believed him.

She dragged her mind away. ‘There was a typhoid outbreak and he died.’

‘And then?’

It was summer and they’d trudged for many days. ‘Our accommodation was needed for the new minister. We came to London because my mother had been offered a job as a housekeeper. When we arrived she was told they wouldn’t employ anyone with a child to look after. She was offered work at night, and for a while I went with her.’ Clementine closed her eyes, recalling a moment so reluctant to emerge that it died inside her mind almost instantly. Somebody had hurt her mother and there had been blood.

‘One day she told me that my father had left money for my education and she took me to the school. She told me I must stay there, because that’s what my father had wanted.’

The man’s eyes sharpened and one peppery eyebrow rose. ‘What was the work she engaged in?’

‘I’m not sure.’

Although now she was older she could guess. She wasn’t about to air those suspicions because she really wanted the position for which she was being interviewed.

The man at the window cleared his throat.

Her inquisitor glanced at the man, who seemed to be about half his age. He was seated, his head propped in his hand, and looking out of the window at the people scurrying in the murky gloom of the street below. The sky threatened rain, but it would wash the soot particles down from the sky and make London look dirtier, rather than refreshing it.

Then she realized he wasn’t looking out, but was in fact observing her reflection in the glass. They hadn’t been introduced yet. Was he her prospective employer?’

When their glances met and connected there was an impression of dark blue eyes and a wide, firm mouth. He was immaculately dressed in grey checked trousers, and a darker knee-length coat with a high cravat. A hat with a curled brim rested on the windowsill, a pair of leather gloves folded neatly on top of a stick with a silver handle that lay nearby.

Her gaze shifted back to her questioner when he asked, ‘Did your mother perform in the theatre?’

‘I’ve already told you I don’t know much about her.’

‘But you must have some notion of how she earned a living.’

‘I cannot recall it with any accuracy. I was almost seven years old when we came to London, and that was fourteen years ago.’

Her mother had two best gowns that were used only for work. One was red and the other green.

Clementine had thought the gowns pretty then, the satin glowing in the candlelight, and as bright as the rouge on her mother’s lips as she’d paraded around the small room that had accommodated them, talking gaily about parties she’d attended and of people she’d met. Clementine had never questioned that it had been less than the truth at the time because she’d been too young to know any better.

As she’d grown older the gowns had begun to reveal the despair of another life. The fabric collected stains and the armpits emitted a sour smell. The fabric rotted into holes. Clementine pushed the thought away, as she always did when it intruded with an alternative occupation. Because she’d loved her mother she could only bring herself to defend her. ‘My mother had a lovely voice. When I was a child she used to sing me to sleep.’

‘Did you earn money to help keep yourself at the school?’

‘My father left an annuity to pay for my school expenses.’ She looked down at her hands. ‘When I was older the annuity ran out and so did my education. I taught at the school for a while.’

‘How did your mother die?’ he asked, alerting Clementine to the fact that this man already knew the answer to the questions he’d put to her and would draw his own conclusion.

She would tell him the truth as she knew it when she was small and embroider it a little to gain his sympathy. ‘I was told she’d developed a cough and had grown very thin. A cold wind was blowing and there had been snow.’ Tears gathered in her eyes. ‘They said somebody had stabbed her and stole the money she’d earned. She’s buried in Potter’s Field.’

His voice softened. ‘How did you end up in the workhouse?’

‘When I was eighteen I asked the school to pay me a wage, but the request was denied. There was an argument.’

‘And you came off second best. I understand you then sought shelter here, where you’ve been teaching the younger children their letters in return for your accommodation and food. You came here two years ago. Since then you’ve been recommended for two positions, both of which you took, and then absconded from. Why?’

She wished he hadn’t asked. ‘They were unsuitable.’

The mysterious man at the window spoke, his voice low, yet as soft as a purr. ‘In what way were they unsuitable, Miss Morris? You copied legal papers for Argus and Shank, who are lawyers. It was regular work and you were in a position of considerable trust. Why did you leave there?’

He wasn’t going to allow her to get away with half-truths. ‘I worked there until I was dismissed. Then I worked in a shop as a clerk for a while, and I sewed seams for a gentleman’s outfitters, where my stitching was pronounced unsuitable.’

The older gentleman said, ‘My companion asked you a question. Why were the positions unsuitable?’

Her colour rose, but from anger this time. ‘In a way I’d prefer not to discuss it with you, sir.’

‘Are we to deduce, then, that you are a morally decent young woman, Miss Morris?’

Living in a workhouse amongst the most destitute of people, and being old enough now to suspect what had really constituted her mother’s employment, Clementine couldn’t pretend not to know what he meant. He had managed to corner her without even trying. She blushed, and her hands went to her face to cover it. ‘Indeed I am, sir. It would be unfair of you to judge me, unless it’s for myself alone … I attend church regularly.’

A muffled snort came from the man at the window. ‘Thank you, Miss Morris.’ He withdrew a silver-cased watch from his waistcoat pocket and gazed at it, before slipping it back in again, in a manner that suggested he might be losing interest in her as a candidate for the position. His eyelashes had a sooty darkness to them that matched his hair. ‘I have a minute or two to spare if you wish to ask me any questions.’

‘I do wish to ask a question … a personal one.’

‘Do you, be damned? I must warn you, I’m not used to having my integrity questioned so you’d better have a good excuse for it.’ The cornflower eyes that confronted her now had lost some of their warmth, and she hesitated.

‘For goodness’ sake, get on with it then.’

‘It’s nothing to do with your integrity, or lack of the same, sir. That must rest in your own estimation. It’s because my previous employers proved unsuitable.’

‘Ah yes … I see. So what’s your question?’

‘Are you a morally decent man?’

He gave a surprised huff of laughter. ‘Well, that certainly answered my question. You’re vexed because I embarrassed you, aren’t you? Do you expect me to answer you honestly?’

‘I did when you asked me.’

‘Of course you did, but that is you, and this is me, and it might not be what you want to hear. Is there such a thing as an entirely decent man? Be careful how you answer though … if you spout religion I shall bite.’

Despite her resolve not to, Clementine threw caution to the winds. ‘I asked you the question, not the other way round.’

‘So you did. Who decides what’s decent, or what’s not in the person who sets himself above others to judge? How narrow or broad should that judgment be? Indeed … from where did it spring?’

‘Are you suggesting I’ve based my question on personal experience?’

‘You certainly have, Miss Morris. I find you impertinent because you are judging me on the foibles of your past employers.’

‘I’m not judging you at all, sir. I merely asked you the same question that you asked me.’

‘Allow me to put this to you, young lady. As a prospective employer, if I promise to refrain from making unwelcome advances towards you – as your previous employers seem to have done – will that satisfy you as to whether I’m a morally decent man or not?’