Digestive Wellness: Strengthen the Immune System and Prevent Disease Through Healthy Digestion, Fourth Edition (129 page)

Authors: Elizabeth Lipski

27

Autoimmune Diseases

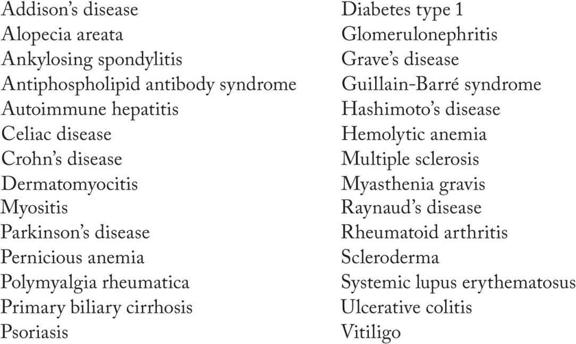

There are many autoimmune diseases discussed in the previous chapters and throughout this one. They include type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, inflammatory bowel diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Behcet’s disease, fibromyalgia, sclero-derma, psoriasis, and Parkinson’s disease.

This chapter gives you a general overview of autoimmune diseases. The definition of an autoimmune illness is one in which your body mistakes healthy cells for harmful ones and attacks them. The function of the immune system is to distinguish self from nonself. In these diseases, this goes awry. There are about 80 known autoimmune diseases, and they can affect virtually every body tissue; many of these have overlapping symptoms, which makes them hard to diagnose. Typically these conditions flare up and then go into remission so that you may feel better for a while.

The most common autoimmune diseases include:

These illnesses affect 23.5 million Americans. You are most likely to get an autoimmune disease if you are female, have a family history of autoimmune conditions, work around solvents or other chemicals, and/or are African, Native American, or Latin in descent. Rheumatoid arthritis is two to three times more common in women. Women have 90 percent of lupus; lupus is also three times more common in African American women than in Caucasian women. Ankylosing spondylitis is one of the rare autoimmune diseases that are more common in men.

In autoimmune diseases the immune system overreacts. There is increased inflammation and oxidative damage from free radicals. Your job is to dampen it down so that it doesn’t see the world as unsafe. (Read

Chapter 9

on inflammation and immunity to get a deeper understanding.)

For an autoimmune illness to thrive it needs the following conditions:

1.

The right genetics

2.

An environmental trigger (could be stress, sunlight, solvents, other chemicals, a virus, bacteria or parasite, heavy metal, pesticide, or some other exposure)

3.

And in some autoimmune conditions, a leaky gut

Alessio Fasano states that for celiac disease to develop, increased intestinal permeability is needed. The relationship between leaky gut and other autoimmune illnesses has also been demonstrated in autoimmune types of arthritis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel diseases, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, autism, primary biliary cirrhosis, psoriasis, Behcet’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. (See

Table 27.1

.) It has not been studied in many other autoimmune conditions yet, so we don’t know if it always plays a role. (For a larger list of diseases associated with leaky gut, see

Chapter 4

.)

These diseases can develop quickly or over many years. You can typically find autoantibodies in your blood many years prior to the onset of the disease. Arbuckle reported that 88 percent of 130 patients who ultimately developed systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) had elevated antibodies 9.4 years prior to the diagnosis. Ask your doctor to look for antinuclear antibodies (ANA) antibodies or other more specific antibodies if you suspect you may have an autoimmune condition. Some of the regular tests that may tip you off include sedimentation rate, complete blood count, elevated C-reactive protein, 25-OH vitamin D testing, and looking for oxidative damage. Functional tests include organic acid testing, food allergy and sensitivity testing, lactulose/mannitol testing for leaky gut, looking at methylation pathways through homocysteine or liver detoxification profiles, and looking at 2:16 ratios of hydroxyestrone. People with one autoimmune illness are more likely to develop additional autoimmune conditions. In 2009 Bardella and colleagues in Milan, Italy, reviewed 297 consecutive patients to determine the prevalence of autoimmune conditions in people with celiac and inflammatory bowel disease. They report that 25.6 percent of people with celiac had another autoimmune condition; 21.1 percent of people with Crohn’s disease also had a second autoimmune condition; and 10 percent of people with ulcerative colitis had a second autoimmune condition. Various studies have reported the incidence of people with celiac disease who also have type 1 diabetes to be between 3 and 6 percent. Togrol reports that of 30 people with ankylosing spondylitis, 11 (36.7 percent) also had positive antigliaden antibodies; 3 of the 11 also had positive antiendomysial antibodies (10 percent). People with autoimmune conditions can also display systemic inflammation. It has been reported that people with lupus have increased risk of developing atherosclerosis and osteoporosis.

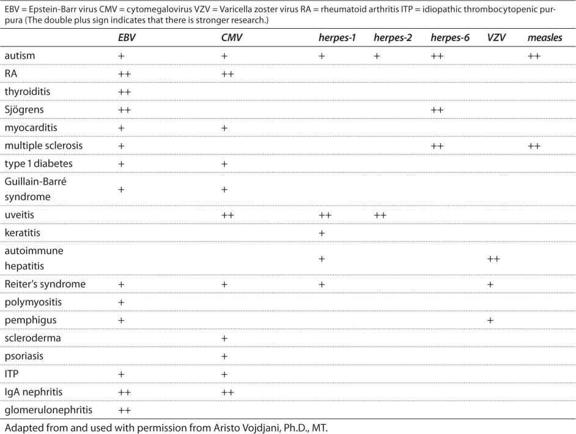

Table 27.1

Association Between Viruses and Autoimmune Disease

In my own practice I have seen people with lupus, scleroderma, and multiple sclerosis (MS) improve significantly when on an elimination diet. Fasting has proven to be effective at reducing inflammation in people with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis; an elimination diet is something that can offer similar results, since fasting cannot be sustained. Although research doesn’t indicate that people with MS have celiac more often than other people, anecdotally there are certainly many people who respond to a gluten-free diet. Hopefully more research will be done in this area.

People with autoimmune conditions can also have problems with GI motility, causing constipation or IBS-like symptoms. Elderly people with Parkinson’s disease were found to have lengthened stool transit time and some malabsorption, which was indicated by decreased mannitol absorption on intestinal permeability testing.

Conventional treatments for autoimmune diseases include medications to reduce inflammation and symptoms, eating well, getting as much exercise as you can without overdoing, getting rest, and using stress-management techniques. Rather than focusing on a single organ or system, using a broader view of the body will get you better results. Try chiropractic treatments, acupuncture, hypnotherapy, and chi gong. Meditate, listen to music, and cultivate methods of training your mind to feel safe and relaxed.

Whatever autoimmune condition affects you, look at the DIGIN model (discussed in

Part II

,

Chapters 3

through

10

) to discover whether you can reduce the severity of the illness and/or reduce the incidence of flare-ups. Reducing inflammation is key, so looking for what triggers your inflammation can be critical. While many people may need prescription medications to reduce inflammation, remember that food is typically our most inflammatory contact. So, trying elimination diets and discovering your specific dietary triggers is important. Healing a leaky gut, caused by your medications or other triggers, is another important step to keeping you healthy. Looking for dysbiosis and the competency of your digestive function can also give you significant information. Think about using probiotics to help modulate your immune system and to reduce inflammation. Consider using natural anti-inflammatory supplements and diet to enable you to reduce your reliance on prescription medications.

Selenium, magnesium, and zinc deficiencies have been associated with autoimmune diseases; low vitamin D levels are also seen in autoimmune conditions with frequency, so have these tested. The incidence of autoimmune conditions rises as you move away from the equator; less sunlight, more autoimmune disease. Vitamin D modulates immune function and inflammation when it is at normal or optimal levels.

28

Behcet’s Disease

Behcet’s disease (BD) is an inflammatory autoimmune disease that affects blood vessels throughout the body, causing vasculitis, an inflammation of the blood or lymph vessel. It was first recognized in 1937 by a Turkish doctor, Hulusi Behcet. It is also known as Silk Road disease because the incidence is greatest in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and the Far East, although there have been cases in people of all nationalities and descent. In the United States, it is more common in women than in men. In Middle Eastern countries, it is more common in men than women. Symptoms most commonly appear in one’s 20s or 30s but can begin anytime. Fifteen thousand to 20,000 Americans have been diagnosed, and many more are undiagnosed.

Symptoms vary depending on where the inflammation is in your body and are due to an overactive immune system. It is chronic and the course is unpredictable. Some people are debilitated by the disease, while a lucky few may go into complete remission. The most common symptoms are recurrent sores in the mouth and genitals and eye inflammation. The sores often have a white or yellow center with redness at the edges and are very painful. There may be additional symptoms, including skin lesions, painful joints, bowel inflammation, and meningitis. Symptoms may involve the nervous system, causing Parkinson-like symptoms; memory loss; impaired speech; hearing loss; loss of balance; blindness; headaches; stroke; and digestive complications, such as bloating, gas, bloody stools, and diarrhea. About 15 percent of people with BD also have heart disease complications. Sufferers sometimes experience a profound sense of fatigue. BD usually presents itself in a rhythm

of remissions and flare-ups of disease activity. It may be worsened by extremes of hot and cold climates or menstrual cycles.

There is no known cause for Behcet’s disease. It is suspected that an environmental exposure, such as a viral or bacterial infection, can trigger the illness in people who are already genetically susceptible.

A large body of research focuses on the insufficiency of antioxidant nutrients and enzymes in people with BD. Glutathione peroxidase levels are lower in people with BD. Glutathione is an enzyme that depends on vitamin E and selenium for optimal function. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity is also diminished. It appears that production of nitric oxide is excessive in people with BD. Use of antioxidant nutrients can bring nitric oxide under control.

One recent study examined levels of vitamin C and malondialdehyde in people with BD. Malondialdehyde is a metabolite that is produced when there is lipid peroxidation, which is a chain reaction requiring antioxidant nutrients. Vitamin C levels were lower in people with BD than in controls, and malondialdehyde levels were higher than in controls. Vitamin C levels were low in people with BD even when the illness was in remission. Different researchers looked at vascular health and found that one hour after IV vitamin C was given there was improved function in the blood vessels.

Another study looked at vitamin E supplementation in BD. It was found that vitamins A and E, beta-carotene, and glutathione levels were lower in people with BD than in controls. When given vitamin E supplementation for six weeks, levels of blood antioxidants rose in the treatment group and were higher than in the untreated control groups.

BD sufferers have significantly increased intestinal permeability. Leaky gut syndrome can be aggravated by use of certain foods. Use of dairy products, gluten-containing foods (see section on celiac disease in

Chapter 24

), and other foods may trigger an immune response and symptoms. Testing for food and environmental sensitivities and allergies makes sense. Use of nutrients such as glutamine, quercetin, probiotics, and antioxidants can be helpful.

No specific diagnostic test exists for Behcet’s disease. Diagnosis is made by elimination of other possibilities and through symptom analysis and is best done by a physician experienced in the treatment of Behcet’s patients. A list of patient-recommended physicians is available at the American Behcet’s Disease Association website at

http://www.behcets.com

. BD may begin gradually at first, with sores that come and go, and may be undiagnosed for a long time; it may also be misdiagnosed as herpes. Like patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, people with BD are often told it’s “all in your head” because they look so healthy. Most of the inflammations

are internal and not readily apparent to family and friends. To be diagnosed with BD, a person must have had recurrent oral ulcers, at least three times in a year. They must also meet two of four additional criteria: recurrent genital ulcers, eye lesions, skin lesions, or a positive “pathergy test.” The pathergy test is simple. The forearm is pricked with a sterile needle, and if a small red bump or pustule occurs, the result is positive. This is very useful in Middle Eastern populations, where 70 percent of people with BD test positive, but less so in Europe and America, where the majority test negative.