Dispatches from the Edge: A Memoir of War, Disasters, and Survival (14 page)

Read Dispatches from the Edge: A Memoir of War, Disasters, and Survival Online

Authors: Anderson Cooper

“GOD BLESS YOU.

You have no idea how happy we are to have you here,” a man says to me Friday morning, shaking my hand in a rubble-strewn lot in Waveland. His name is Charles Kearney, and he and his wife, Germaine, have come to visit what’s left of their home.

“Where are the people?” Charles shouts. “Why are people dying? I’ll tell you why! Because there aren’t enough National Guard troops to come here! They’re all already dispersed! I mean, I hate to go there, but why else can it be? They’re in Iraq and everywhere else.”

“Foreign countries are getting better care than we get,” Germaine says.

Charles and Germaine lost their house on Honey Ridge Road. So have their parents, who lived a few blocks away.

They evacuated on Sunday to Mobile. They’ve been coming back each day, ferrying food and water to friends from their hotel.

“I’m speechless. What the hell is going on and why are people still on the freaking interstate in New Orleans?” Charles says, his face turning red with anger. “I don’t care whose fault it is, but fix it now. And these people who are saying, ‘You know, well we tried! We warned them. They could get out!’ Well people don’t have the resources to get out. They have nowhere to go.”

Charles and Germaine take me to where Charles’s parents’ house used to stand. His mother and father, Myrtle and Bill Kearney, are picking up plates from their yard.

“Oh goodness, Anderson, I don’t want to look like transient trash,” Myrtle says, laughing when she sees me. “This house was so pretty. My father-in-law built it painstakingly. He would come to the lot, he would study the best views to put the windows.”

“Look, our whole kitchen counter’s over there,” Germaine says, pointing.

Myrtle is holding a cracked plate in her hand.

“What are you going to do with that?” I ask

“Probably frame it,” she says, laughing. “For God’s sake, I’m an artist! I’ll probably paint it.”

Myrtle didn’t want to evacuate at first, but on Sunday, Charles convinced her she had to go.

“I vacuumed my house to the moon before we left to go for the hurricane,” she says, shaking her head. “I cleaned the house so that when we came back we would have a pleasant environment to come back in.”

“We stood right here in this driveway and laughed at her as we left,” Charles says.

“And wait,” she adds. “You wanna hear the best? Y’all are gonna die laughing. I collect rocks. I came out, picked out all my rocks and brought ’em inside and hid ’em! The rocks are gone. And the carpet’s gone! And it’s gonna be so damned easy to move, you won’t believe it!”

I laugh with Myrtle, and realize it’s the first time in days. Later, however, away from her family, her laughter is gone, her smiling face falls away.

“There’s nothing that can prepare you for this,” she says. “I have not cried yet. And I’m probably gonna go away and lose it completely. With all my joking and all my Myrtle-isms, I’m probably gonna lose it really bad. But right now…what can you say?…And this is the God’s truth for me: we have each other, right here. Some people don’t, and some people don’t have water to drink right now. And some people have dialysis and they need drugs. We can’t complain about this. This happens to other people, and they come back from it. And we’re going to come back from it, too.”

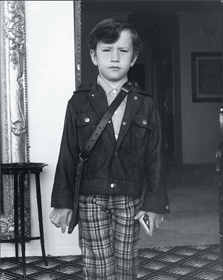

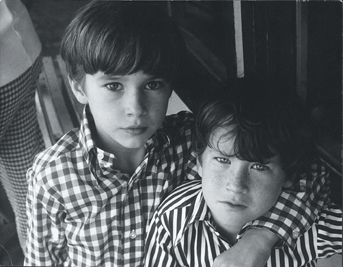

My brother and I, circa 1969. While I was still in my mother’s womb, Carter labeled me “Baby Napoleon,” but he was the true leader of our childhood campaigns.

This portrait of me was taken by my father, Wyatt Cooper. I was about eight years old.

On a trip to Quitman, Mississippi, in 1976. My father wanted us to understand and appreciate the shared soil in our blood.

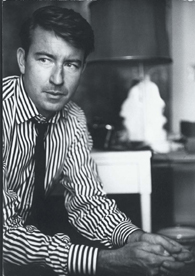

My father in 1963, around the time he met my mother. As a child, I never saw the resemblance between us; now I look at pictures of my father and I see my face.

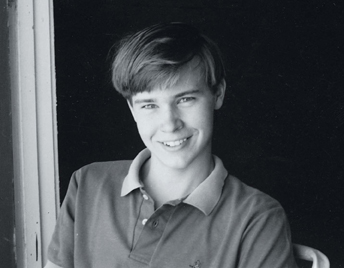

Carter at sixteen. After my father’s death, both of us retreated into separate parts of ourselves, and I don’t think we ever truly reached out to each other again.

Christmas, 1986: My mother, Gloria Vanderbilt, Carter, and I.

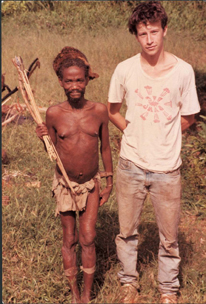

Posing with a Pygmy chief in Zaire, 1985. I was seventeen and had left high school a semester early. Africa became a place I’d go to forget and be forgotten in.

Moments after landing at the Sarajevo airport in Bosnia, 1993. I’m wearing a Kevlar vest and helmet for the first time. After a few trips, however, I rarely put them on.

Working out of a destroyed beachfront hotel in Sri Lanka, January 2005. Christmas decorations still hang from the lobby ceiling.

BRENT STIRTON/GETTY IMAGES FOR CNN

Searching for the bodies of two children, Jinandari and Sunera, in a hospital morgue in Sri Lanka, January 2005.

BRENT STIRTON/GETTY IMAGES FOR CNN

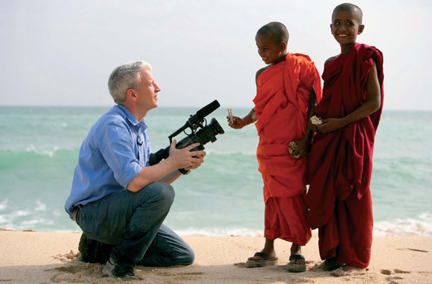

Children training to become monks on a beach near Kamburugamuwa, Sri Lanka, January 2005.

BRENT STIRTON/GETTY IMAGES FOR CNN

Early morning at a U.S. military checkpoint, Baquba, Iraq, December 2005.

THOMAS EVANS

In Maradi, Niger. During the summer of 2005, 3.5 million Nigeriens were at risk of starvation. These kids were some of the lucky ones not suffering from malnutrition.

RADHIKA CHALASANI/GETTY IMAGES FOR CNN