Do Cool Sh*t (24 page)

Authors: Miki Agrawal

Things to Consider Every Time You Travel (Just in Case!)

- Sleeping bag:

You just never know where you may end up. - Floor mat:

Again, you just never know where you may end up. - Pillow:

I literally cannot go anywhere without my pillow. Carry a good pillow, for goodness sake.

For the most part, when it comes to adventuring, just get outside your comfort zone and look for the authentic magic all around you. Go with intention and your life will be all the richer for it! I can’t wait to hear your stories at docoolshit.org.

How to Build Your Tribe

I am who I am because of who we all are.

—U

BUNTU

A

asif yelled into the loudspeaker, “On your mark . . . Get set . . .

Go!

”

Rads and I took off as fast as we could. “Left, right, left, right, turn!!! Left, right, left, right . . .” As we hit the halfway point of the three-legged race (a race we, ahem, have won every year), we could see our top competition, Andrew and Dave, move past us.

We had already blown past Tony Hsieh and Dan Rollman (in addition to all six of the other teams competing in this final heat), and it was down to our two teams.

“Come on, let’s go faster!” I yelled. We knew that our last shot at coming back and winning was if they messed up on the final turn.

As we approached the turn, Rads said, “Don’t forget to start with your left foot after the turn!”

Out of the corner of our eyes, we saw Andrew and Dave get to their final turn.

Sure enough, their knees knocked into each other’s, their third leg started to wobble, and that was our window of opportunity to go for gold.

We made the turn, left foot first, and shot past Andrew and Dave, who sprawled in the middle of the course. As we laughed and hugged, we couldn’t help reveling in the fact that we remained Agra-Palooza’s fifteenth-annual reigning champion of the three-legged race.

We looked around us—everyone was either laughing their faces off, rolling around in the grass with their partners attached to them, or trying to tenaciously run toward us to congratulate us with their legs still tied together. In that moment, all felt right in the world. Our community was together and happy.

Our childhood was all

about games and functions. If it wasn’t soccer games, it was badminton on Sundays and Hindi or Japanese functions on weekends.

For our birthdays, we threw two parties: one we called the kids birthday party and the other we called the adults birthday party. At the kids party, we invited all of our friends from school, and at the adult one, our parents invited all of their friends. It was basically an excuse to throw two birthday parties for us. But, hey, we didn’t mind! That meant more presents for us! Since Yuri’s birthday is January 28, and Radha’s and mine is January 26, we threw most of our birthday parties together as kids.

Our parents made up two really fun games that all of our friends grew up with and looked forward to each year. One was called Lucky Dip, and the other was called Yes-No.

Lucky Dip was a game where our parents would put a bunch of candy and chocolate out on our sprawling basement floor and we would have to stand behind a line and throw an eight-inch ring around the goodies. Whatever candy the ring landed on, we got to keep. Of course my parents put the more expensive and decadent chocolates farther away, so it was harder to throw the ring around them.

Well, as you can imagine, kids who grew up playing this game from five years of age to eighteen years old would have enough experience at this point to take a running jump to launch themselves from the starting line in hopes to get the ring around the most expensive chocolate. It was amazing to see the progression and tenacity over the years.

The other game, Yes-No, was by far the most competitive at our birthday parties. My parents always started by warming up the group with questions like, “Miki is older than Radha—yes or no?” (Answer: No, of course not, can’t you tell?) Then they would get right into it: “The current president of North Korea is ——, yes or no?” When you’re six years old and playing this game, it’s a bit terrifying.

There were two supernerds who kept winning Yes-No every year (Tejas and Vijay, you know who you are), and finally, after so many years, and much to everyone’s surprise, at our eighteenth birthday party another kid in our class—Vikaas—won. To this day, I think Vikaas still has “Reigning Yes-No Champion” on his résumé and it is still a source of great pride (and a great conversation starter in interviews).

Having experienced this engaging ritual of games for all to enjoy and participate in for so many years, we loved how energized people were when they left the party and we wanted to continue these kinds of traditions. So when we moved out of the house, we started two more events, both still using the house and the surrounding pool and yard as our staging grounds: one that was called Agra-Palooza and the other our New Year’s Eve Eve party that always happened on December 30, the day before New Year’s Eve.

Agra-Palooza takes place the third week of July, when about fifty to seventy-five friends and family members descend on our parents’ place for a sleepover weekend (basically every inch of the house is covered with people passed out). Picture the barbecue version of the Olympics except with chickpea curry and samosas on the snack table and veggie burgers on the grill. It has physical challenges like a three-legged race, egg toss, pool-diving competition, round-robin Ping-Pong tournament, volleyball, and basketball games. It culminates with martinis in the Jacuzzi and long conversations about world issues. People leave Agra-Palooza with deeper, more meaningful friendships and a feeling of togetherness.

New Year’s Eve Eve is our “Intellectual Olympics,” where my parents create riddles about the current events for the year and hide clues all over the house so guests have to run around, look for clues, solve the riddles, and then put the answers on a paper that had a hangman finish, where we would have to unscramble the final word. It is intense and always a blast.

One thing both parties have in common is the talent segment, where it’s mandatory for all guests to come with a talent to share—either a song, dance, act, poem, scene, story, magic, yoga pose, art on the spot, or anything creative and expressive. It forces even the shyest of our friends to come out of their shells and perform in front of an audience.

There were other evenings of celebration and community as well. Whenever my parents had my dad’s work friends over, they would do a night of poetry readings; his colleagues had to bring and perform a poem in front of everyone. Watching a bunch of engineers act out poetry was better than any comedy show imaginable.

On certain holidays, like Easter, we always wanted to come home not only because we wanted to hang out with our parents but also because they would create an intense, engineering-like Easter egg hunt where we had to solve geographic riddles to get to the eggs. “From base camp, walk eighty paces north-easterly and you will see a branch hanging ever so slightly over a babbling brook. Walk east from there, fifty paces, and you will find the egg nestled beneath a man-made creation.” We loved the competition.

Every time a holiday came around, we knew we had something to look forward to, which of course encouraged us to go home for every holiday. Our parents figured us out!

I carried that method out with my friends once I moved out on my own, planning parties with games and activities. I mean, how many times can we go to parties where we just go, eat, hang out, talk, and leave? I’ve always believed that to get everyone to have a great time, and to feel a deepened connection within the group, there had to be participation from everyone, even the quieter ones. The goal was to have everyone leave feeling happier, more loved, more understood, and alive!

We didn’t know it back then, but we were assembling the building blocks of a solid community: built with the foundation of unanimous participation.

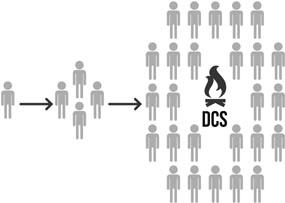

This brings me to the event that defines unanimous participation: Burning Man.

As described in chapter 15, Burning Man is an art and music festival in the middle of the desert of Nevada, and it is, without a doubt, the utopian ideal of what “community” truly means.

This otherworldly festival started with just a few people in 1986 and has grown over the past twenty-seven years to an event that has a thriving community most likely in the hundreds of thousands and now draws sixty thousand people from around the world to participate. Each year.

Breathtakingly spectacular art installations are conceived and constructed, costumes are planned and fantastically created—even the cars are illuminated and designed with art in mind—and when you look around the desert and see the most creative and fantastical art, costumes, cars, and more, it’s enough to bring even the most unsentimental to tears. For me, I’m moved because people are creating things for the love of it and the desire to share it with others, and not for any other reason.

This festival grew into what it has become partly because at the root of it all, humans naturally want to be able to express themselves in movement, style, art, poetry, or any which way they are inspired to do so; they want to be heard, understood, and to belong to something where they have an important role to play.

The founder, Larry Harvey, crafted a set of ten principles for Burning Man—basically, a set of guidelines for the ever-growing community.

He said that the principles “were crafted not as a dictate of how people should be and act, but as a reflection of the community’s ethos and culture as it had organically developed since the event’s inception.”

Here are his ten principles. See if you’re not just a little inspired by them. If you can imagine a world that lived by these principles, can you imagine what kind of world it would be?

R

ADICAL

I

NCLUSION

Anyone may be a part of Burning Man. We welcome and respect the stranger. No prerequisites exist for participation in our community.

G

IFTING

Burning Man is devoted to acts of gift giving. The value of a gift is unconditional. Gifting does not contemplate a return or an exchange for something of equal value.

D

ECOMMODIFICATION

In order to preserve the spirit of gifting, our community seeks to create social environments that are unmediated by commercial sponsorships, transactions, or advertising. We stand ready to protect our culture from such exploitation. We resist the substitution of consumption for participatory experience.

R

ADICAL

S

ELF-

R

ELIANCE

Burning Man encourages the individual to discover, exercise, and rely on his or her inner resources.

R

ADICAL

S

ELF-

E

XPRESSION

Radical self-expression arises from the unique gifts of the individual. No one other than the individual or a collaborating group can determine its content. It is offered as a gift to others. In this spirit, the giver should respect the rights and liberties of the recipient.

C

OMMUNAL

E

FFORT

Our community values creative cooperation and collaboration. We strive to produce, promote, and protect social networks, public spaces, works of art, and methods of communication that support such interaction.

C

IVIC

R

ESPONSIBILITY

We value civil society. Community members who organize events should assume responsibility for public welfare and endeavor to communicate civic responsibilities to participants. They must also assume responsibility for conducting events in accordance with local, state, and federal laws.

L

EAVING

N

O

T

RACE

Our community respects the environment. We are committed to leaving no physical trace of our activities wherever we gather. We clean up after ourselves and endeavor, whenever possible, to leave such places in a better state than when we found them.

P

ARTICIPATION

Our community is committed to a radically participatory ethic. We believe that transformative change, whether in the individual or in society, can occur only through the medium of deeply personal participation. We achieve being through doing. Everyone is invited to work. Everyone is invited to play. We make the world real through actions that open the heart.

I

MMEDIACY