Do Not Say We Have Nothing: A Novel (41 page)

Read Do Not Say We Have Nothing: A Novel Online

Authors: Madeleine Thien

You may say that that is not love, and I would laugh at you for presuming to know what another’s love isn’t and what his love is.

–ZIA HAIDER RAHMAN

,

In the Light of What We Know

W

HEN JIANG KAI, MY FATHER

, left China in 1978, one of his suitcases was filled with more than fifty battered notebooks. The notebooks contained drafts of self-criticisms whose final pages must have been submitted, years earlier, to a superior or an authority figure. Self-criticism, samokritika in Russian, 检讨 (jiǎn tǎo) in Chinese, required that the person confess his or her mistakes, repeat the correct thinking of the Party and acknowledge the authority of the Party over him or her. Confession, according to the Party, was “

a form of repentance that would bring the individual back into the collective.” Only through genuine contrition and self-criticism could a person who had fallen from grace earn rehabilitation and the hope of “resurrection,” of being returned to life.

I arrived in Shanghai on June 1, 2016. From my hotel room, I looked down at a city wreathed in mist. Skyscrapers and condominiums shouldered together in every direction, erasing even the horizon.

How the city mesmerized me. Shanghai seemed, like a library or even a single book, to hold a universe within itself. My father had arrived here in the late 1950s, a child of the countryside, in the wake of the Great Leap Forward and a

man-made famine that took the lives of 36 million people, perhaps more. He had perfected his music, dreamed of both a wider world and a better one, and fallen in love. Day after day, Kai had bent over his desk, feverishly writing and copying pages, revising and reimagining his life and his moral code. We were not unalike, my father and I; we wanted to keep a record. We imagined there were truths waiting for us–about ourselves and those we loved, about the times we lived in–within our reach, if only we had the eyes to see them.

Summer fog slowly erased Shanghai from view. I stepped away from the window. I showered, changed and went down to the subway.

Underground, people gazed at screens or tapped at phones, but many drifted, as I did, through their thoughts. Near me, an old woman discreetly savoured cake, phones chimed and honked, a mother and daughter repeated the multiplication table and a child refused to disembark.

Unexpectedly, the train braked. The old woman stumbled, her cake went flying, and she fell into my lap.

For a moment, she was suspended in my arms, our faces inches from one another. A big whoop went up from people around us, followed by jovial applause. A child reprimanded her for eating on the train, another wanted to know what kind of cake it was. The woman laughed, the sound so unexpected, I nearly dropped her. She was in her late sixties, around the same age Ma would be now. In my imperfect Mandarin, I tried to give her my seat, but the woman waved me off as if I had offered her a ticket to the moon.

“Save yourself, child.” She said something else, words which sounded like, “Enough crumbs, no? Enough.”

“Yes,” I said. “Enough.”

She smiled. The subway hurried on.

I could feel my jet lag now; the world around me seemed far away as if I was carried in a jar of water. A man opened a newspaper

so wide, it covered his wife and daughter. Behind them, in the windows, their reflections shifted, one behind the other.

—

In his self-criticisms, my father wrote of his love of music and the fear that he “could not overcome a desire for personal happiness.” He denounced Zhuli, gave up Sparrow and cut all ties to the Professor, his only family. He wrote of how he had stood by helplessly while first his mother, then his young sisters, and finally his father died; he said he owed his family everything, and had a duty to life. For years, Ba tried to abandon music. When I first read his self-criticisms, I glimpsed my father through the many selves he had tried to be; selves abandoned and reinvented, selves that wanted to vanish but couldn’t. That’s how I see him, sometimes, when my anger–on behalf of Ma, Zhuli, myself–subsides and turns to pity. He knew that leaving these self-criticisms behind would endanger others, yet to destroy them was impossible, so he carried them first to Hong Kong and then to Canada. Even here, he would begin new notebooks, denouncing himself and his desires, yet he could not find a way to reinvent himself or change.

Last week, preparing for this trip, I came across a detail: in 1949, Tiananmen Square retained its place as the centre of political power in China by reason of analytic geometry.

An architect, Chen Gang, posited the Square as the “zero point.” He quoted Friedrich Engels: “

Zero is a definite point from which measurements are taken along a line, in one direction positively, in the other negatively. Hence the zero point is the location on which all others are dependent, to which they are all related, and

by which they are all determined

. Wherever we come upon zero, it represents something very definite: the limit. Thus it has greater significance than all the real magnitudes by which it is bounded.”

That summer of 1966, the year Zhuli died, was the zero point for my father. Like hundreds of thousands of others, he went to Tiananmen Square to pledge his loyalty to Chairman Mao and

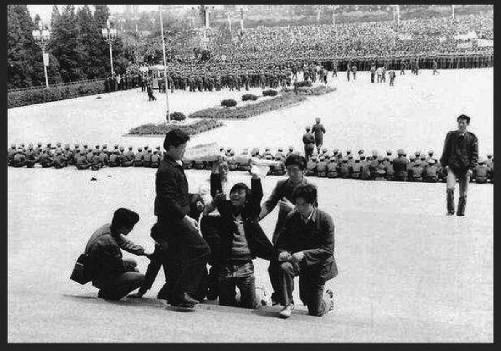

commit himself to fānshēn: literally, to turn over one’s body, to liberate oneself. Decades later, he watched on television as three university

students stood before the Great Hall of the People bearing a letter to the government. It was April 22, 1989. The three lifted their arms, raised the petition high and fell to their knees, as if seeking clemency. Behind them in Tiananmen Square, more than 200,000 university students reacted in shock and then grief.

Why are you kneeling?

Stand up, stand up!

This is the People’s square! Why must we address the government from our knees?

How can you kneel in our name? How?

The students, who came from every political and economic background, were distraught. But the three stayed where they were, tiny figures, the petition heavy in the air, waiting for an authority figure to receive it. Ten, twenty, thirty minutes passed, and they remained on their knees. Behind them, agitation grew. When Chinese leaders failed to respond, the Tiananmen demonstrations began in earnest.

I exited the subway at Tiantong Road, emerging at an intersection where condominiums, half-constructed, opened like giant staircases to the sky. I had been to this quarter before: Hongkou is where Swirl and Big Mother Knife grew up before the war, and it is where Liu Feng, a violinist once known as Tofu Liu, now lives.

At different times, Hongkou has been a clothing district, the

American-Japanese concession, and, during the rise of Hitler and the Second World War, the Shanghai Ghetto. In the 1930s, the Shanghai port could be legally entered without passport or visa; some forty thousand Jewish and other refugees from Germany, Austria, Russia, Iraq, India, Lithuania, Poland, the Ukraine and elsewhere arrived here, bringing not only their languages and traumas, but also their music.

I continued south, past a sidewalk argument, around three men, their bodies fully stretched out on their motorbikes, playing cards.

At Suzhou Creek, I reached the Embankment Building. Up on the tenth floor, Mr. Liu was waiting for me. I had contacted him on WeChat and, at first, when I said I was the daughter of Jiang Kai, he had been wary. But when I told him I was looking for Ai-ming, the daughter of Sparrow, he transformed entirely. Now, the first time we were meeting in person, he greeted me as if he had known me all my life. “Ma-li!” he said. “Come in, come in! Have you eaten? My daughter picked up these sugar pyramids….”

Books, sheet music, compact discs, cassettes and records occupied every inch of space. After a thirty-year teaching career at the Shanghai Conservatory, he had retired last month and moved his office home. “Don’t trip,” he said. “I don’t have insurance.”

We went sideways through the kitchen and into the living room. Across the river, Shanghai’s dramatic skyscrapers floated, surreal. We were a world away, but only a single generation, from the city my father had known.

Mr. Liu told me that, since the 1990s, he had watched this skyline come into existence. “When my daughter was born, none of these buildings were even a scribble on paper. These three,” he said, pointing out the tallest ones, “were meant to symbolize the past, present and future. But the government’s words were very boring. Instead, people call them the ‘three-piece kitchen set.’ You see? There’s the bottle opener. The whisk. And…what would you say in English? A turkey baster.”

I laughed. “I think the whisk is the most beautiful, Mr. Liu.” It was a cylindrical spiral like a ribbon in motion.

“I agree. But Shanghai still looks like a tool belt. By the way, don’t be so formal! Please call me Tofu Liu. That’s what everyone calls me, even my grandkids.”

Before us, the lights of the buildings began to glow.

Tofu Liu turned his back on the city. We sat down at a little table where someone had been sorting pencil crayons. He told me that he had entered the Shanghai Conservatory the same year as Zhuli. “We both studied under the same violin teacher, Tan Hong. My father was a convicted rightist, a counter-revolutionary, just like Zhuli’s father. I was a little in love with her, even while I envied her talent.” During the Cultural Revolution, the Conservatory had closed. “Not one piano survived. Not one.” He himself was sent to a camp in Heilongjiang Province, in the frozen borderlands of the Northeast. “We had to wear either blue, grey or black. Our hair had to be short. We had to wear the same kind of cap. That was only the beginning. The wind was glacial. We were beside a river, and on the other side of the river was Russia. We worked in coal mines. We had no skills in this work and almost every week, someone was seriously injured or killed. The Party replaced them. The only books available to us were the writings of Chairman Mao. We had daily self-criticism and denunciation sessions. This went on for six years.”

In 1977, when the Cultural Revolution ended, Liu ran away from the camp and returned to Shanghai, where he sought out his former teacher, Tan Hong.

“We talked about Zhuli for a long time and about others we had known. Then Professor Tan asked me, ‘Tofu Liu, do you wish to come back to the Conservatory and complete your studies?’

“I said I did.

“ ‘After everything that’s happened, why?’

“His question devastated me. How could I pretend that music was salvation? How could I commit myself to something so

powerless? I had been a miner for six years, there was coal dust in my lungs, I’d broken all the fingers of my right hand, how could I possibly hold a violin? I told him, ‘I don’t know.’ But he kept pushing me for an answer. It wasn’t enough for him to hear that I loved music, that it had comforted me all this time, and I had promised myself that if I survived, I would devote my life to it. There were thousands of applicants for a handful of spots at the Conservatory. They all loved music as much as I did. Finally I told him the truth. I said, ‘Because music is nothing. It is nothing and yet it belongs to me. Despite everything that’s happened, it’s myself that I believe in.’

“Tan Hong shook my hand. He said, ‘Young Liu, welcome back to the Conservatory. Welcome home.’ ”

Tofu Liu showed me his mementos. These included a photo of Zhuli performing with the Conservatory’s string quartet when she was nine years old and a wire recording of Zhuli and Kai playing Smetana’s “From My Homeland,” which Liu had kept hidden until the end of the Cultural Revolution.

“But, Mr. Liu, how could you possibly hide these things?”

He shrugged, smiling. “Before I was sent to the Russian border, I cut a small hole in the parquet floor of my bedroom in Shanghai. You know how hard parquet is! All I had was a kitchen knife. It took me two terrible weeks. I was convinced that Red Guards would burst into the room and that would be the end of me. I buried a dozen wire recordings, some photos and scores, and my violin. Ten years later, when I pulled it up, there was a nest of mice inside the violin…But look at this wire.” He lifted the spool and showed it to me. It was pristine. “Would you like to hear it?”