Do Penguins Have Knees? (13 page)

Read Do Penguins Have Knees? Online

Authors: David Feldman

The five- and six-pointed star “tradition” seems to be purely a twentieth-century one. I’ve seen hundreds of badges from the nineteenth century, and they ranged from the traditional policeman’s shield to a nine-pointed sunburst. Five- and six-pointed stars predominated, but in no particular order—there was no definite plurality of five points in one group and six points in another. I have noticed, however, that the majority of the

locally

made star-shaped badges produced outside of Texas were six-pointed. There may be a reason for that.

When you cut a circle, if you take six chords equal to the radius of the circle and join them around the diameter, you will find that the chords form a perfect hexagon. If you join alternate points of the hexagon, you get two superimposed equilateral triangles—a six-pointed star. In order to lay out a pentagon within a circle—the basic figure for cutting a five-pointed star—you have to divide the circle into 72-degree arcs. This requires a device to measure angles from the center—or a very fine eye and a lot of trial and error. Since many badges, including many deputy sheriff and marshal badges, were locally made, it would have been much easier for the blacksmith or gunsmith turned badgemaker for a day to make a six-pointed star.

Who says that the shortage of protractors in the Old West didn’t have a major influence on American history?

Submitted by Eugene S. Mitchell of Wayne, New Jersey. Thanks also to Christopher Valeri of East Northport, New York

.

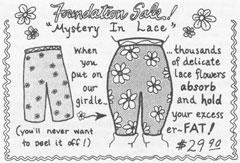

When

You Wear a Girdle, Where Does the Fat Go?

Depends upon the girdle. And depends upon the woman wearing the girdle.

Ray Tricarico, of Playtex Apparel, told

Imponderables

that most girdles have panels on the front to help contour the stomach. Many provide figure “guidance” for the hips and derriere as well.

“But where does the fat go?” we pleaded. If we cinch a belt too tight, the belly and love handles plop over the belt. If we poke ourselves in the ribs, extra flesh surrounds our fingers. And when Victorian ladies wore corsets, their nineteen-inch waists were achieved only by inflating the hips and midriff with displaced flesh. Mesmerized by our analogies, Tricarico suggested we contact Robert K. Niddrie, vice-president of merchandising at Playtex’s technical research and development group. We soon discovered that we had a lot to learn about girdles.

First of all, “girdles” may be the technical name for these undergarments, but the trade prefers the term “shapewear.” Why? Because girdles conjure up an old-fashioned image of undergarments that were confining and uncomfortable. Old girdles had no give in them, so, like too-tight belts, they used to send flesh creeping out from under the elastic bands (usually under the bottom or above the waist).

The purpose of modern shapewear isn’t so much to press in the flesh as to distribute it evenly and change the contour of the body. And girdles come in so many variations now. If women have a problem with fat bulging under the legs of the girdle, they can buy a long-leg girdle. If fat is sneaking out the midriff, a high-waist girdle will solve the problem.

Niddrie explains that the flesh is so loose that it can be redistributed without discomfort. Shapewear is made of softer and more giving fabrics. The modern girdle acts more like a back brace or an athletic supporter—providing support can actually feel good.

“Full-figured” women are aware of so-called minimizer bras that work by redistributing tissue over a wider circumference. When the flesh is spread out over a wider surface area, it actually appears to be smaller in bulk. Modern girdles work the same way. You can demonstrate the principle yourself. Instead of poking a fatty part of your body with your finger, press it in gently with your whole hand—there should be much less displacement of flesh.

Niddrie credits DuPont’s Lycra with helping to make girdles acceptable to younger women today. So we talked to Susan Habacivch, a marketing specialist at DuPont, who, unremarkably, agreed that adding 15 to 30 percent Lycra to traditional materials has helped make girdles much more comfortable. The “miracle” of Lycra is that it conforms to the body shape of the wearer, enabling foundation garments to even and smooth out flesh without compressing it. The result: no lumps or bumps. Girdles with Lycra don’t eliminate the fat but they “share the wealth” with adjoining areas.

Submitted by Cynthia Crossen of Brooklyn, New York

.

What

Do Mosquitoes Do During the Day? And Where Do They Go?

At any hour of the day, somewhere in the world, a mosquito is biting someone. There are so many different species of mosquitoes, and so much variation in the habits among different species, it is hard to generalize. Some mosquitoes, particularly those that live in forests, are diurnal. But most of the mosquitoes in North America are active at night, and classified as either nocturnal or crepuscular (tending to be active at the twilight hours of the morning and/or evening).

Most mosquitoes concentrate all of their activities into a short period of the day or evening, usually in one to two hours. If they bite at night, mosquitoes will usually eat, mate, and lay eggs then, too. Usually, nocturnal and crepuscular female mosquitoes are sedentary, whether they are converting the lipids of blood into eggs or merely waiting to go on a nectar-seeking expedition to provide energy. Although they may take off once or twice a day to find some nectar, a week or more may pass between blood meals.

If the climatic conditions stay constant, mosquitoes tend to stick to the same resting patterns every day. But according to Charles Schaefer, director of the Mosquito Control Research Laboratory at the University of California at Berkeley, the activity pattern of mosquitoes can be radically changed by many factors:

1. Light (Most nocturnal and crepuscular mosquitoes do not like to take flight if they have to confront direct sunlight. Conversely, in homes, some otherwise nocturnal mosquitoes will be active during daylight hours if the house is dark.)

2. Humidity (Most will be relatively inactive when the humidity is low.)

3. Temperature (They don’t like to fly in hot weather.)

4. Wind (Mosquitoes are sensitive to wind, and will usually not take flight if the wind is more than 10 mph.)

Where are nocturnal mosquitoes hiding during the day? Most never fly far from their breeding grounds. Most settle into vegetation. Grass is a particular favorite. But others rest on trees; their coloring provides excellent camouflage to protect them against predators.

A common variety of mosquito in North America, the anopheles, often seeks shelter. Homes and barns are favourite targets, but a bridge or tunnel will do in a pinch. Nocturnal or crepuscular mosquitoes are quite content to rest on a wall in a house, until there is too much light in the room. In the wild, shelter-seeking mosquitoes will reside in caves or trees.

We asked Dr. Schaefer, who supplied us with much of the background information for this Imponderable, whether mosquitoes were resting or sleeping during their twenty-two hours or so of inactivity. He replied that no one really knows for sure. We’re reserving

When Do Mosquitoes Sleep

? as a possible title for a future volume of

Imponderables

.

Submitted by Jennifer Martz of Perkiomenville, Pennsylvania. Thanks also to Ronald C. Semone of Washington, D.C

.

What

Does the “CAR-RT SORT” Printed Next to the Address on Envelopes Mean?

Reader Jeff Bennett writes: “CAR-RT SORT is printed on a lot of the letters I receive. Obviously it’s got something to do with mail sorting, but what does it stand for?”

Not unlike us, Jeff, it sounds like you’ve been receiving more than your share of junk mail lately. CAR-RT SORT is short for Carrier Route Presort and is a special class of mail. As the name implies, to qualify for the Carrier Route First-Class Mail rate, mailers must arrange all letters so that they can be given to the appropriate mail carrier without any sorting by the postal system. Each piece must be part of a minimum of ten pieces for that carrier; if there are not ten pieces for a particular carrier route, the mailer must pay the rate for Presorted First-Class Mail. (Presorted First-Class Mail costs more than Carrier Route because it requires only that the mail be arranged in ascending order of ZIP code.)

Don’t expect to see CAR-RT SORT on the envelopes of your friends’ Christmas cards. Carrier Route Mail must be sent in a single mailing of not less than 500 pieces. And if they really have ten friends serviced by one postal carrier, it would be cheaper for them to hand-deliver the cards.

Submitted by Jeff Bennett of Poland, New York. Thanks also to Matt Menentowski of Spring, Texas

.

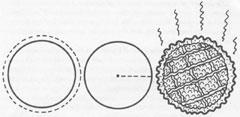

The history of “pi” is so complex and fascinating that whole books have been written about the subject. Still, if you want to make a long story short, it can be boiled down to the explanation provided by Roger Pinkham, a mathematician at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey:

There are two Greek words for perimeter,

perimetros

and

periphireia

. The circumference of a circle is its perimeter, and the first letter of the Greek prefix

peri

(meaning “round”) used in those two words was chosen.

Mathematicians attempted to calculate the pi ratio before the birth of Christ. But it wasn’t the ancient Egyptians or Greek mathematicians who first coined the term. San Antonio math teacher John Veltman sent us documentation indicating that although pi was earlier applied as an abbreviation of “periphery,” the first time it was found in print to express the circle ratio was in 1706, when an English writer named William Jones, best known as a translator of Isaac Newton, published

A New Introduction to Mathematics

. “Pi” did not enjoy widespread acceptance until 1737, when Jones’s term was popularized by the great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler.

So what did the ancient Greeks call the ratio? They probably did not have a handy abbreviation. Veltman explains:

It appears that even the Greek mathematicians themselves did not use their letter pi to represent the circle ratio. Several ancient cultures did their math in sentence form with little or no abbreviation or symbolism. It is amazing how much they achieved without such an aid. Archimedes, born about 287

B.C

., is said to have determined that the value of pi was between 3 10/71 and 3 1/7 (or in our decimal notation, between 3.14084 and 3.142858).

In the centuries that followed, mathematicians in other countries produced even more precise calculations: Around

A.D

. 150, Ptolemy of Alexandria weighed in with his value of 3.1416. Around

A.D

. 480, a Chinese man, Tsu Ch’ung-chih, improved the figure to 3.1415929, correct to the first six numbers after the decimal point.