Do You Sincerely Want To Be Rich? (32 page)

Read Do You Sincerely Want To Be Rich? Online

Authors: Charles Raw,Bruce Page,Godfrey Hodgson

Tags: #Non Fiction

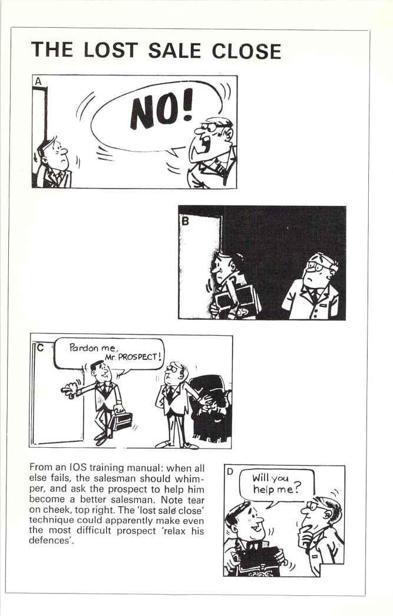

In which the salesmen find the last great market. Under the remarkable Eli Wallitt, the sales force becomes a kind of chainletter game, and it multiples like the amoeba.

It was in Germany that the sales operation finally stood revealed in its pure essence: as an elaborate system for enriching the salesmen - or rather specifically the sales managers - advertised as a crusade to bring capitalism to the masses.

For a time the German operation was a triumph. Within three years from 1966 to 1969, it shot up from being no more than one among a couple of dozen territories around the world, until it was virtually half of IOS: almost half the clients, fully half the salesmen, and almost half of the face volume of sales.

But the expansion in Germany was bought at a cost which contributed substantially to the sales operation's overall loss. To compensate for that loss, management was driven to more and more speculative expedients. The discovery of those expedients caused the share price to collapse, and brought on the apocalypse. And to a very great extent that fuse of causation led back to Germany.

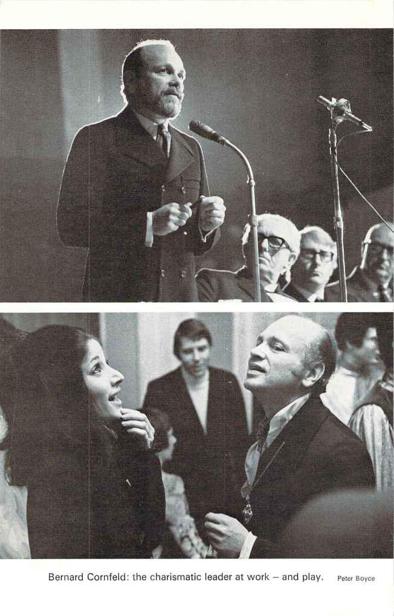

There is a quality about those last extravagant years of IOS in Germany which reminds one of one of the great religious revivals, IOS was not spoken of there simply as an investment company among others, more or less successful. Both its supporters and its opponents discussed it in terms of ideology, as if Cornfeld's vague rhetoric about 'people's capitalism' really added a new thesis to Marx's dialectic.

The IOS salesmen, one German IOS executive wrote, 'did not

simply offer a product or a service. They offered a

Weltanschauung'.

That is the word Germans use for an all-embracing philosophical view of the universe.

Weltanschauung'.

That is the word Germans use for an all-embracing philosophical view of the universe.

Eli Wallitt, who actually devised and controlled the German miracle, put it a little differently to us. Salesmen, he said sadly, are 'fantasy oriented'. Their motivation lies in the future. It is a dream, but a dream that keeps them working. Most of them, he conceded, made only a 'marginal' living. A few - and Wallitt was one of them - made a fortune. Nowhere was the fantasy richer or more effective, for a while, than in Germany.

There were several reasons why IOS should have taken root in Germany with the vigour of an idea whose time has come.

In the middle 1960s, Germany was almost completely unfettered with any regulations to hamper the foreign mutual fund salesman. The West German mark, for a start, was freely convertible. 'There is nothing to stop any German putting all his capital into ioodm notes, getting into his car, driving across into Switzerland, and changing it all into Swiss francs,' said a leading West German banker. 'It's a

Ganovenwunderland -

a hoodlum's paradise.

Ganovenwunderland -

a hoodlum's paradise.

German domestic mutual funds were carefully regulated by a law of 1957, in some respects more strictly than the sec regulates American funds. But foreign and offshore funds in Germany were not regulated at all until 1969. So long as they did not distribute their profits as dividend, they were not even taxed, for no income was due when dividends were automatically reinvested to buy additional units.

West Germany is, as everyone knows, one of the wealthiest countries in Europe. What is not so widely known is that the habit of owning stocks and shares is less widespread in Germany than in any comparably wealthy country. In 1960, for example, fewer than one million West Germans owned any shares, as against three and a half million people who did in Britain, a less wealthy country. Two world wars, with revolution at the end of the first, and the destruction of the economy after the second, and above all the traumatic inflation of the 1920s, have made the older half of the German middle class ultra-wary of the stock market.

The character of the German markets has reinforced this attitude. There are no brokers in Germany, as such. The banks act as brokers, and operate the markets between them. In the late 1950s, both the Christian Democratic government and the big banks tried to encourage small investors. The government denationalized Volkswagen on terms favourable to the small shareholder. The banks started their own mutual funds.

But in the 1960s, though the economy, by and large, went from strength to strength, the stock market emphatically did not. The new investors who had come gingerly into the market in the late 1950s burned their ringers when the market fell by more than 50% in 1960-1.

The economy, however, continued to flourish, and by the middle 1960s, more and more people had money burning a hole in their pockets, or at least deposited in 4% savings accounts. The net result was that by the beginning of 1967 IOS was ideally poised for a successful sales campaign.

More than one of the German bankers, officials and journalists we talked to about the IOS phenomenon reminded us of another factor which cannot be ignored: the extraordinary trust in, and admiration for, all things American of the generation of Germans who had been young in 1945 - which was the generation who had money saved by the 1960s.

More than anywhere else in Europe, the old values had been discredited in Germany. Germans turned to America and identified American ways with everything that was modern, democratic, progressive. Mutual funds were new, they were modern, they were American. Hundreds of thousands of Germans in the young-middle-aged generation were ready to believe that if mutual funds were criticized by the bankers, then that just showed how frowsty or self-interested the bankers were.

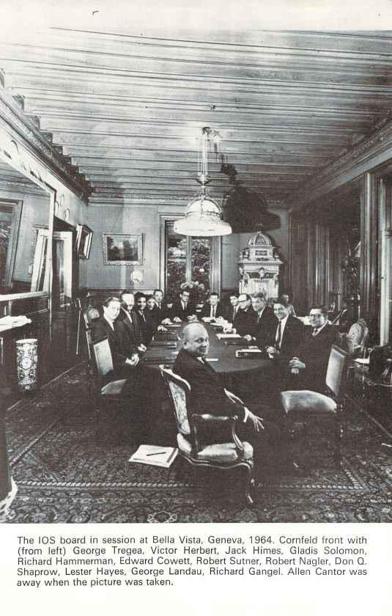

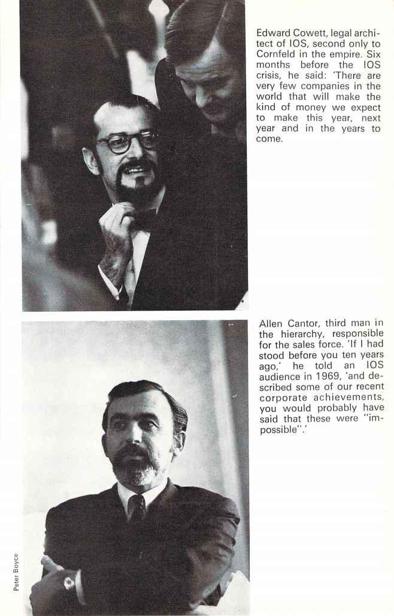

Why was IOS so slow to realize that this huge market was waiting for it in Germany? It had after all been very active in Germany since 1957. Most of the leading individuals in the sales management - from Bernie Cornfeld down through Allen Cantor, Victor Herbert, Jack Himes, Eli Wallitt - knew Germany well from having sold programmes to the American military there themselves for years.

The truth is that for seven years Cornfeld was in the position of a man who doesn't realize he is sitting on a goldmine. It was not, for example, until mid-1963 that the first IOS sales material

was produced in German. And in 1960 Cornfeld actually sold the IOS dealership in Germany to Wolfe Frank who had been the chief interpreter at the Nuremburg trials. It was not until 1963 that he decided to buy it back, and go into Germany in a big way.

It was Eli Wallitt who grasped the potential of the German civilian market. After his first stint in the military market in Germany, he had been back to New York to work for ics (the IOS subsidiary there) recruiting people to work overseas. He came back to Geneva in 1962 and worked as a sales executive. He guessed that there must be a lot of small savers in Germany who would be wanting to get back into the equity market again after the 1961 drop. He was right.

Wallitt is one of the most intriguing of the IOS inner circle and one of the wealthiest today.

1

He is not an obviously ambitious type. He is tall, with curly grey hair and the suggestion of a scholar's stoop. He is highly intelligent; not merely shrewd, but given to speculative conversation like a born intellectual, and prone, like the social worker he was - for considerably longer than Bernie Cornfeld-to theorizing at length about human motivation, including his own. In business, WaUitt's style was to remain in the background, using his intelligence to control people and events indirectly.

1

He is not an obviously ambitious type. He is tall, with curly grey hair and the suggestion of a scholar's stoop. He is highly intelligent; not merely shrewd, but given to speculative conversation like a born intellectual, and prone, like the social worker he was - for considerably longer than Bernie Cornfeld-to theorizing at length about human motivation, including his own. In business, WaUitt's style was to remain in the background, using his intelligence to control people and events indirectly.

When this adroit and interesting man set out to conquer Germany in 1963, he took with him one lieutenant, and one recruit. The lieutenant was Ossi Neduloha. The recruit was Raimund Herden, who became the IOS general manager in Hamburg. Ossi Neduloha is a broad, stocky, blond, young man - not yet thirty at the time - of Czech descent and Austrian nationality. He joined IOS as an office boy in the earliest days, and then went to work in the mailroom to perfect his English and French.

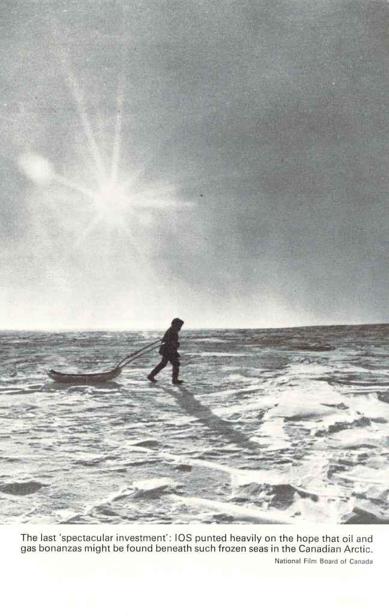

He started selling in Africa, but his first big coup came in the Canadian Arctic, where he found - not oil - but highly paid Canadian servicemen with nothing to spend their money on. They signed up as clients in droves. Next he moved on to Central America, where he learned Spanish and sharpened up his sales technique in a tough school.

Neduloha has had little formal education, but he does have both formidable determination and what has been described as 'a wayward Viennese charm'. Many of the salesmen came back from the road in the middle Sixties in search of a manager's more dependable profits. None timed their move or chose their territory as perfectly as Ossi, and only two or at most three others in the whole IOS sales organization - Wallitt himself, Felberbaum and conceivably Werner Kunkler - earned as much money.

Raimund Herden had been out in Iran, not as an IOS salesman, but working for Brown Boveri, the big Swiss electrical engineering firm. Before that he had worked for the Deutsche Bank. He had in short a thorough German business training: he had the performance figures of every mutual fund at his fingertips, and was never at a loss for words, either in the office, or at the dinner parties which he advised his managers to frequent as assiduously as he did himself.

Eli Wallitt is quite open about his philosophy of management. He told us that he wanted his German operation to be as tight as he could make it administratively, and as loose as possible on the sales side. For a former Socialist, he has an unusual belief in the merits of competition.

Wallitt reasoned that strong personalities make the best salesmen, and that a strong personality is hard to direct. He was quite prepared to have four or five general managers treading on each others toes in Munich, so long as they got on with the job of selhng. And they certainly did that.

Wallitt and Neduloha's organization multiplied like an amoeba. Cells were always splitting off, with a strong salesman as their head. As this man moved up the managerial ladder, he recruited more and more salesmen under him. And in the course of time they in turn split off and started their own amoeba-empire.

The best way of illustrating how this worked in practice is to compare the structure of the German sales operation in 1964, when Wallitt had had time to get it fairly started, with the shape it had assumed by 1969. In this way one can also follow how individual early birds were wafted up the override tree by the efforts of the men underneath them.

In 1964 Neduloha was the regional manager for Germany. (Wallitt discreetly kept in the background.) There were only six branches in the region. Branch a was based on the Rhine-land-Ruhr industrial area, and coming geographically closest under the eye of Neduloha in Dusseldorf, it was divided between three managers, Gerhard Schicht in Cologne; a veteran of the IOS operation in South America called Bodo von Unruh, in Essen; and a third man called Jochen Freetown, whom we have been unable to trace.

Branch b was run by Raimund Herden, who had moved from Dusseldorf to Hamburg, and spent a good deal of time disputing the boundaries of his territory with Ossi, who however retained an override on Herden's business. Herden was listed as having nineteen salesmen.

Branch c, with 21 salesmen, was managed by Larry Palmer, a former paratroop captain and goalie in the United States squad which won the gold medal for ice-hockey in the Squaw Valley Olympic Games of 1960. Palmer had his offices in Frankfurt.

The remaining three branches were all in Munich, under Wallitt's more immediate eye. Two of them, e and f, with fourteen and eleven salesmen respectively, were managed by Americans, Joseph 'Bru' Brubaker and Pat Lucier. Branch d was run by Werner Kunkler, and had already 45 salesmen.

Altogether, the 156 salesmen in Germany achieved $4.8 million of face volume in that 1964 contest, little more than half the volume done by the 21 salesmen in Brazil, the champion region at that time. As a region, Germany came eighth out of 23 regions in the world.

By 1969 Germany, as a whole, sold a contest volume of $257 million, an increase of over 5,000% in five years! Eighteen separate regions in Germany sold more than the whole of Germany had done five years before. One of Werner Kunkler's 1964 salesmen alone, now a general manager, had 512 salesmen under him, more than three times the number of the entire German sales force in 1964. And each of the six branches of 1964 had swollen to a whole complex of regions and divisions, with a dozen or more branches under them.

The geometric progression of the expansion shows up most clearly in Werner Kunkler's command. It was Kunkler who came closest of anyone to beating the Americans in IOS at their own game. He did it by relying on the classic German military virtues: order, hierarchy, discipline, and application.

Kunkler had been a doctor of psychology, an actor, and in insurance, but before that he had lost several fingers of one hand as a tank captain on the Russian front in World War II.

He had been sold an IOS programme by Bernie Cornfeld's cousin, Hardy Reisser. 'When the fellow had gone,' Kunkler explained characteristically afterwards, 'I worked out how much money he had made off me. And I said "If he can do that, you can do it too!" '

By 1969, eight of Kunkler's most successful salesmen of five years before had become managers. Several of them had worked up to the title, and the override, of a general manager.At the beginning of 1964 he quit his job as an insurance loss assessor, and started his dizzy climb up the IOS ladder. In each of the three years, 1967, 1968 and 1969, the salesmen under Kunkler's orders did more than 10% of IOS's whole business, worldwide.

Kunkler's secret was not his personal persuasiveness as a salesman, but the methodical way he deployed his troops from Munich all over South Germany.

Other books

Woman Thou Art Loosed! 20th Anniversary Expanded Edition by T. D. Jakes

Justice for Mackenzie by Susan Stoker

After the Fall: Close and Confined (Taboo Erotica) (Eden Harem Book 1) by Merchant, Anya

Chocolate Box Girls: Sweet Honey by Cathy Cassidy

The Devil's Waltz by Anne Stuart

Follow Me by Joanna Scott

The Rule Book by Kitchin , Rob

The Zoo at the Edge of the World by Eric Kahn Gale

Hidden Agenda by Alers, Rochelle

Shifting Shadows by Sally Berneathy