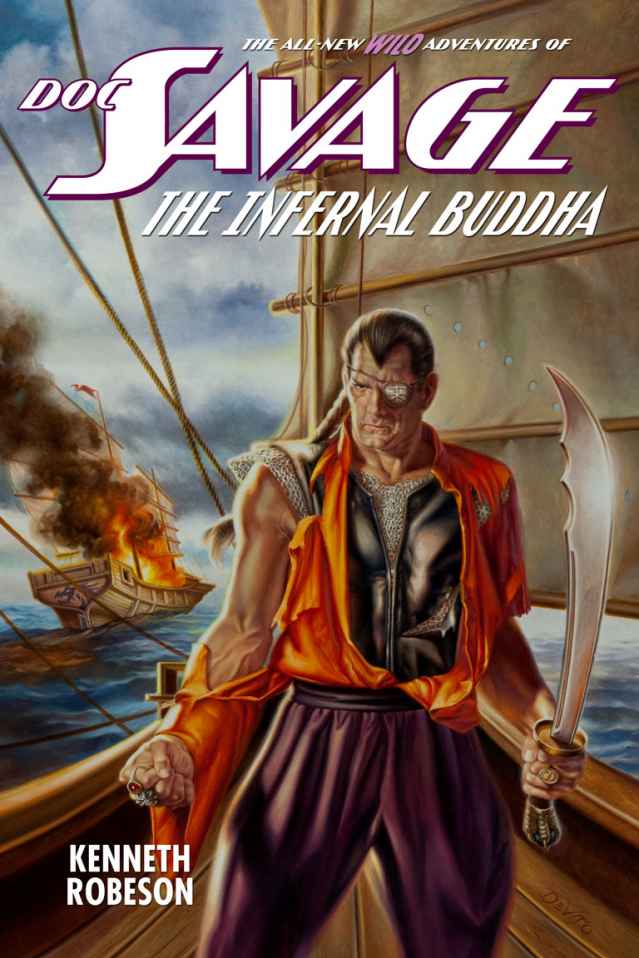

DOC SAVAGE: THE INFERNAL BUDDHA (The Wild Adventures of Doc Savage)

Read DOC SAVAGE: THE INFERNAL BUDDHA (The Wild Adventures of Doc Savage) Online

Authors: Kenneth Robeson,Lester Dent,Will Murray

Tags: #Action and Adventure

A Doc Savage Adventure

by Will Murray & Lester Dent writing as Kenneth Robeson

cover by Joe DeVito

Altus Press • 2012

The Infernal Buddha copyright © 2012 by Will Murray and the Heirs of Norma Dent.

Doc Savage copyright © 2012 Advance Magazine Publishers Inc./Condé Nast. “Doc Savage” is a registered trademark of Advance Magazine Publishers Inc., d/b/a/ Condé Nast. Used with permission.

Front cover image copyright © 2012 Joe DeVito. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Designed by Matthew Moring/

Altus Press

Like us on Facebook:

The Wild Adventures of Doc Savage

Special Thanks to Lee Baldwin, James Bama, Dr. Tahir Bhatti, Jerry Birenz, Condé Nast, Jeff Deischer, Dafydd Neal Dyar, Matthew Moring, Ray Riethmeier, Art Sippo, Anthony Tollin, Howard Wright, The State Historical Society of Missouri, and last but not least, the Heirs of Norma Dent—James Valbracht, Shirley Dungan and Doris Lime.

For James Bama, who reimagined Doc Savage for a new generation—

And whose artistic vision we are proud to continue….

Strange People

THE MAD MYSTERY of the infernal Buddha, as it came to be called, started east of Singapore, which is a speck of an isle off the lowermost tip of the Malayan Straits. It was a fitting day for a mystery to begin, there being a fog, which was highly unusual for that part of the South China Sea.

Dang Mi, who was destined to play a major role in the unbelievable events to come—although he didn’t know it yet—sprawled in the shade of the mainsail on the poop deck of his two-masted Chinese junk,

Devilfish.

The name was a rare bit of honesty. She was as devilish a hellship as ever plied the South China Sea.

From hull to clumsy-looking batten sails, she was also as black as an octopus. A round white orb was painted on either side of her bows, after the superstitious custom of the Orient, which ascribed to such painted eyes the ability to see danger ahead.

Dang Mi had heard of Doc Savage, fabulous man of might, who was also to become embroiled in the mystery about to start. By repute, Doc Savage was a more fearsome foe of evildoers than Scotland Yard, the Royal Mounted and the G-Men put together. Doc Savage had never gotten wind of Dang Mi, so far as the latter knew. Dang planned to keep it that way.

There was good reason for this. Dang Mi was a follower of a very old and exceedingly dishonorable profession. Dang Mi was a gentleman of fortune. That was the polite term for it. Dang was a pirate. He did not fly the Jolly Roger, nor had he occasion to make a captive walk the proverbial plank, but he was a pirate nonetheless, one of the few still prowling Asiatic waters. The British Navy had pretty much cleansed the China coast of piracy, particularly in the area of Bias Bay—which meant only that the surviving pirates had sought out more welcome waters.

That had all been before Dang Mi’s advent in the Malay Straits. He was a relative latecomer to the profession of piracy. And although his crew consisted of a polyglot collection of cut-throats and smugglers—mostly Dyaks and Malays, with a sprinkling of Siamese and Borneo wharf rats—Dang Mi was a white man. An American, to be precise.

Dang Mi’s honest name was Hen Gooch—which possibly explained why he didn’t mind being known as Dang Mi. In truth, he came upon his Oriental cognomen quite by accident.

A salty cuss by disposition, Hen was free with epithets. But there was one saying he preferred above all others.

“Dang me,” he often complained—often enough for his crew to mistake the exclamation for Pidgin English. They thought he was saying, “Me, Dang”—Dang being a perfectly respectable name for a Chinese pirate.

Eventually, Hen Gooch got them straightened out. But not before he decided he liked the sound of Dang Mi for a name. Loosely translated, it meant, “Like a Demon.”

It was to be suspected that the numbers of lawful authorities in America—both North and South—and Europe who had designs on Hen Gooch’s future, had a little to do with the change of name—not to mention inspiring Dang Mi’s preoccupation with sunning himself daily to keep his hide from becoming too white.

There were times he smeared collodion at the corners of his eyes to give them a slanted aspect. He wore his hair long and shaggy, in order to conceal the indisputable fact that the top of one ear had been cut off some time in the past. Back in the United States, this bit of rough justice branded a man as a common horse thief. Horse thieves are not hanged so much as they were in the formal frontier era, so earmarking them is seen as the next best thing.

Dang Mi was certainly not the first horse thief to adopt a change of career. He was probably not even the first horse thief to turn pirate. But from such humble beginnings, he had certainly ranged far from his native badlands.

Dang Mi’s finger had been in many a darksome mystery in its time. But it had never touched anything quite the equal of the enigma of the infernal Buddha.

THE mystery made its advent in the guise of an airplane which came buzzing out of the north.

The instant he heard the plane, Dang Mi bounced up from baking his hide in the brazen Oriental sun. He ripped orders. The

Devilfish’s

radio operator got busy.

The

Devilfish,

for all the fact that she was a fat-bottomed junk, and equipped with a brace of old-fashioned smoothbore deck cannon concealed by removable iron shields affixed to her gunwales, had her modern aspects. Dang Mi was an up-to-date rascal. Fastened to the hull was a submarine listening device, as sensitive as money could buy, which could pick up the noise of any vessel within a good many miles and, furthermore, give a general idea of its location. The radio installation was also complete for short or long wavelengths.

“I think the perishin’ plane must be off a British Navy hooker,” said Dang, who had picked up a sprinkling of British slang during his sojourn in this corner of the globe. “Listen for the noise of a cutter’s screws. Sparks, you fish around with the bloomin’ radio and see if the plane reports our location.”

The interval immediately following was a tense one. The British Navy had of late years inaugurated a disquieting habit of sending a search plane to spot a suspicious vessel and radio its location to a Customs cutter. Dang Mi feared that was happening now.

Aboard the

Devilfish

at the moment were a half-dozen assorted aliens, all destined for surreptitious landing on the Malay coast. Not the least member of this little group was a gentleman known as “Poetical” Percival Perkins, a gangling lad who recited poetry and swindled people with about equal skill.

No, it would be unfortunate if the British customs authorities searched the

Devilfish

just now.

UP until this point, the plane had been a noise in the fog, no more. A throaty, firm noise, such as would be made by a good speed-cowled motor with many big cylinders. The British Navy had such motors, which was, in truth, what had alarmed Dang Mi, formerly Hen Gooch. He had made a study of British Navy planes for the same reason that a burglar entering a strange town looks around to see what kind of uniforms the cops wear.

Dang Mi knew the plane was more likely to see them than they were to see the plane, the

Devilfish

being the larger. This was the case. Abruptly, the plane tilted one wing down and the other up, and began circling their position curiously. It reminded Dang of a big bumblebee swinging on the end of a string.

“Sit tight, you brown blokes,” Dang Mi warned his crew and passengers, all of whom had meantime donned conical bamboo coolie hats to look like innocent Chinese seafarers. A few were adorned with appropriate pigtails.

The name of the ebony vessel had been changed for the moment, also, by substituting a canvas strip across the stern nameplate. The identification forward had been altered likewise.

These precautions were old stuff and might fool the British Navy, or might not. These waters are overflowing with two-masted fishing junks, their seaworthiness being first-rate.

“Blast the dang world,” gritted Dang Mi, for the moment mixing his Limehouse with his Pumpkin Buttes, Wyoming, from which he originally hailed.

The plane was going to land. It swooped close to the mast tops and the pilot leaned out of the cabin window and with an arm made gestures indicating his intention.

Dang Mi had been blessed by nature with intensely black hair that enabled him to pass for Chinese, Malay or Indo-Chinese as the situation required. He felt like tearing out some of that hair now. The plane overhead did not have the regulation markings, but it was the same type of plane used by the British Navy, so Dang Mi had no doubts.

“Break out Iron Mike,” rapped Dang.

IN seaman’s parlance, an “Iron Mike” is the telegraph instrument used to signal the engine room crew. The

Devilfish

was hardly large enough to require such a convenience, but Dang liked the appellation.

In this case, Iron Mike was actually a Maxim machine gun. Crew used pry bars to expose the concealed deck well in which it was normally stored, and set it up. When they were done, the bulky, serrated barrel assembly jutted forward of the tripod mount. Hard, ugly with the canvas gullet of a brass catcher hanging empty by the breech. Extra ammunition sat handy in gunny sacks on either side of the weapon.

“No sign of a cutter over the listener,” reported the Malay who had been at the submarine detector.

“Plane not using ladio,” advised Sparks, a Chinese, whom everyone except Dang invariably called “Spalks.”

“Which makes her a bit of all right,” leered the renowned Dang. “He ain’t reported us. ’ Twouldn’t surprise me none if he didn’t.”

Dang Mi’s men, all of whom were Asiatics, heartily wished they had never seen the fat, peaceful looking white man whom they had decided was no less than their tribal earth devil come to life, and who was their captain, incidentally, without paying them.

They waved their arms. But they did not wave them fast enough for Captain Dang Mi, who hauled two nickel-plated six-shooters from leather holsters hanging from his bullet-stuffed cartridge belt, and began to shoot. He fired first one gun, then the other. He pierced an ear here, stung the bottom of a foot there. It was amazingly accurate two-handed shooting.