Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (17 page)

Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

New York was such a pity, but at Max’s Kansas City we won

We all shot the shit at the bar

With Johnny O’Toole and his scar

And then old Clive Davis said he’s surely gonna make us a star

Just the way you are

But with all our style, I could see in his eye

That we were going on trial

It was no surprize

G

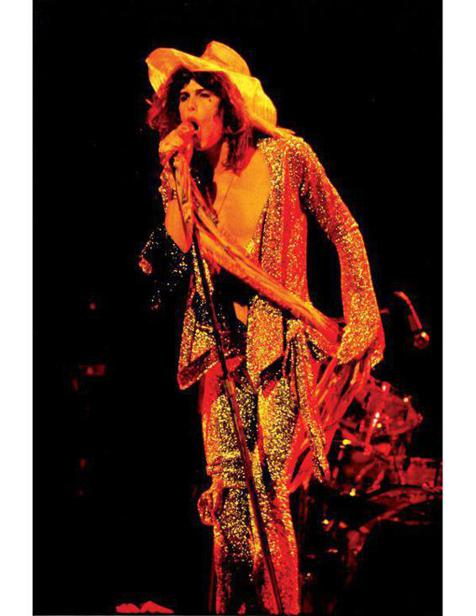

litter Queen, 1972. (Outfit was designed by me and Francine Larness. I love you, girl!) (Ron Pownall for Aerosmith)

Aerosmith got signed to Columbia Records in 1972 by Clive Davis for $125,000. We stayed up all night celebrating, but we knew that just getting a record contract wasn’t the be-all and end-all of our career. When we finally woke up and saw what was in it, the smell didn’t seem so sweet. The contract said we had to deliver two albums a year—which would be impossible on account of the fact that we were out on the road touring nonstop, fast and furious, to support the singles the radio stations were playing. That’s the way you did it.

F

rank Connally was smart enough—and rich enough—to know that the band needed to go off by itself and write without the women around. And he obliged me. The motherfucker knew . . . he

knew.

If Joe and I could write songs, we would take the group to a whole other level. And to do that we needed to live in a house together, rent a place for two weeks. Let’s go.

First he put us into the Sheraton Manchester, north of Boston, and then in a couple of suites at the Hilton near the airport (where I wrote the lyrics to “Dream On”), and then in a house in Foxboro, where we lived the week before recording the first album. I’d wake up in the morning and say, “Tom, let’s go and see if we can play this song.” I’d play a few bars of “Dream On” on the piano and say, “Well, what if . . . Tom plays these notes.” I sang them; he played them and it was fucking perfect . . .

perfect.

That’s where “Dream On” started to come together. The other guys followed my piano. I said, “Joe, you play what my right hand’s doing. Brad you play the left hand.” When we did that—hello, synchronicity!

So, the band did go out to Foxboro alone, but . . . there are exceptions to every rule. Joey brought a girl, his girlfriend, and one night says to me, “She wants to

do

you and you can have her.” And that was the best Christmas present Joey ever gave me.

W

e’d been together about two or two and a half years when we got ready to record the first album. We were poised to strike. I had nine years of being a hippie behind me, smoking pot, going to the Village, reading Ouspensky, and wanting to bust out of my own placenta, eggshell, or wherever the fuck I came from.

When I wrote the music to “Seasons of Wither” I grabbed the old acoustic guitar Joey found in the garbage on Beacon Street with no strings. I put four strings on it, which is all it would take because it was so warped, went to the basement, and tried to find the words to match the scat sounds in my head, like automatic writing. The place was a mess, and I moved all the shit aside, put a rug down, popped three Tuinals, snorted some blow, sat down on the floor, tuned the guitar to that tuning, that special tuning that I thought I came up with . . .

Loose-hearted lady, sleepy was she

Love for the devil brought her to me

Seeds of a thousand drawn to her sin

Seasons of Wither holding me in

One of the highlights of my career was being in Greenwich Village with Mark Hudson and coming across a guy sitting on a rag playing a guitar. His feet were black from the streets he’d walked. He looks up at me and starts playing “Seasons of Wither,” note for note, exactly as I wrote it. Someone was looking at my painting.

“M

ama Kin” was a song I brought with me when I joined Aerosmith. The lick for “Mama Kin” was from an old Bloodwyn Pig song, “See My Way.” If Mick can say, “Oh, we got ‘Stray Cat Blues’ from ‘Heroin’ on the Velvet Underground’s first album,” I can cop to a little larceny on our part.

Keep in touch with Mama Kin.

Tell her where you’ve gone and been.

Livin’ out your fantasy,

Sleepin’ late and smokin’ tea.

“Route 66” was our Stones mantra, a way of finding our groove. It was the riff I asked the band to play again and again in the basement of BU to show them what

tight

playing meant. When I started rehearsing with the jam band, we

jammed

as good as anyone, but to survive the rock ’n’ roll world, we’d have to write songs and get under the hood . . . that’s why I had Aerosmith play that lick from “Route 66” over and over and over until we were as tight as a midget’s fist.

We played it so many times it eventually morphed into the melody for “Somebody” on our first album. “One Way Street” was written at the piano at 1325 with the rhythm and harp coming from “Midnight Rambler.” On “Movin’ Out,” the first song I wrote with Joe, you can hear him quoting Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile.” He quotes the Beatles and the Stones elsewhere on the record. The rhythm of “Write Me” (originally “Bite Me”) came from something Joey was playing. But the intro comes from the Beatles “Got to Get You into My Life,” because at that point we didn’t know how to write hooks.

“Dream On” was the only song I hadn’t finished by the fall of ’72, so I moved to the Hilton at the airport in Boston while we were doing sessions at Intermedia Studios for the first album. I just buckled down one night and wrote the rest of the lyrics . . . and I remember reading them back and thinking, “Where did I get that from? It’s strange rhymage.” I loved Yma Sumac, the Inca Princess with the staggering five-octave voice. “

Look in the mirror, the paaaaasst is gounnnnnnnnh.”

That’s the Yma Sumac vocal swoop. Singers generally don’t go from the bridge to the chorus with a bridge note like that, but it worked melodically for me. It’s like the Isley Brothers singing “It’s Your Thing,” where after the solo the first line of the verse is sung an octave higher, then slides down an octave for the next.

I would sing along with Yma Sumac, that eardrum-piercing banshee shriek, beginning in the highest register. She sang these strange, otherworldly songs in movies like

Secret of the Incas

and looked like an over-the-top Hollywood version of an Inca queen. Sam, Dave, and Sumac—an inspirational trinity.

In October 1972 we started work on our first album at Intermedia Sound. It took only a couple of weeks to record because we’d been playing many of the songs—especially the covers—for over a year. Adrian Barber, an English engineer who’d worked with Cream and Vanilla Fudge, produced the album. It was recorded on very primitive equipment—sixteen-track to AGFA two-inch oxide tape.

The band was very uptight. We were so nervous that when the red recording light came on we froze. We were scared shitless. I changed my voice into the Muppet, Kermit the Frog, to sound more like a blues singer

. Kermit Tyler.

I would unscrew the lightbulbs so no one would know we were recording. One of my favorite things to say before we recorded a song was “Play it like you would if no one’s looking, guys.” They’d be recording and we’d be so nervous, making mistakes and hesitating, and I’d go, “Fuck being nervous! Just play!” We would run through the song live a couple of times and then Adrian would shout. “Yes! It’s got fire; it’s got the bloody fire!”

As soon as we’d cut that first song, “Make It,” upon listening to playback, I knew we’d nailed it. I’d done “Sun” at some studio in New York and all that shit. “Sun” was stiff and forced, but I knew that with this band, once we got out of our own way we were going to ace it. And with a great guitar player like Joe in the band, if we stayed true to our

fuck-all

. . . everything would sound like Aerosmith.

I used an exaggerated black-speak voice on all the tracks except “Dream On.” I thought it was really cool. The only problem was, nobody knew it was me.

“Ah say-ng lak dis”

because I didn’t like my voice and it was early on and I wanted to

put on

a little. To this day, some people still come up to me and ask, “Who’s that singin’ on the first album?” I was into James Brown and Sly Stone and just wanted to sound more R&B.

“Dream On” deserved strings, but we couldn’t hire an orchestra on the kind of budget we had for our first record, so I used a Mellotron to fill out the sound. It was like an early sampling device employed by the Beatles. I used it to add strings and flutes to “Dream On,” while doing lines off my keyboard. I thought the Mellotron would do the trick, coming in on the second verse.

In the end we decided not to use “Major Barbara” and did Rufus Thomas’s “Walkin’ the Dog” (via Stones) instead, which was tighter than a crab’s ass from doing it in the clubs for so many years. On the first ten thousand copies of the album they spelled it “Walkin’ the Dig.” If you happen to find a copy, it’s worth about five thousand dollars. You’d figure with all the cash and power the labels had, they’d learn how to spell. That, coupled with the fact that “Dream On” didn’t come out until after the second album, made me think . . .

if things didn’t go down, we wouldn’t go up

. I believe in life imitating art, but who is art and why is he imitating me anyway?

Of all the songs I wrote on that first album, “One Way Street” has some of my favorite lyrics:

You got a thousand boys, you say you need ’em

You take what’s good for you and I’ll take my freedom

The original title was “Tits in a Crib.” That’s what I wanted to call it, but that was forty years ago and things weren’t as loose as they are today. I wrote it about this girl I was seeing. I’d talk her into coming over because she was such a trip . . . did me sooo good. She had a baby, and when she came over she’d bring the kid and his crib, saying, “I have no babysitter tonight.” She used to fuck me to death in that crib. The line “

You got a thousand boys, you say you need ’em

” came from where we were living at the time, in Needham, Massachusetts. I’ll do anything for a rhyme. I can’t think of that girl’s name now, but god, she was the skinniest, cutest little trollop.

The style of the first album was raw, filled with relentless attitude. We were a bunch of boys who had never seen the inside of a recording studio. You can practically hear our hearts racing on every track. Barber’s atmospheric technique resulted in tracks that were so

open

you could literally

feel

the tracks breathing . . . it was almost transparent.

We knew the road was where we could conquer. Sure it was sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll, but we wanted to add one more word to the equation . . .

gynormous

. We needed to get to the people, so we did it ourselves. Played every small town and went to every station in the fucking country. Sure it’s old school, but it worked.

Aerosmith was all about sex . . . music for hot chicks and horny boys. Loud, bone-rattling rock for chopped and channeled cars and customized Harleys. If you’re driving along and you hear “Movin’ Out” you’re gonna go, “I wanna get the fuck out of here and

dance

!” Roll the window down and let the world in on your little secret. Well, the gist of Aerosmithism is: cars + sex. Booty-shake music. We rocked like a bitch.

Creem,

April 1973, wrote “Aerosmith is as good as coming in your pants at a drive-in at age 12. With your little sister’s babysitter calling the action.” Okay, at least somebody out there was getting us.