Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (9 page)

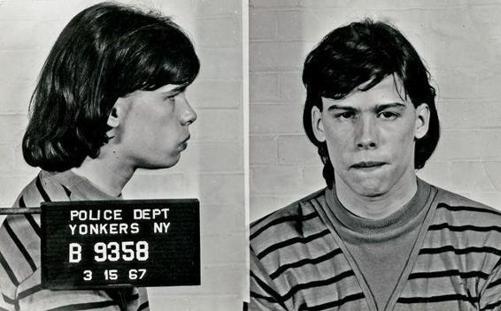

B

usted for smoking pot—

imagine that. I’d be nineteen in eleven days.

My whole life’s been like that. Of course, I also got kicked out of Roosevelt High, but they let me be the guitar player in

The Music Man

at the end of the year

.

Yeah, there was trouble in River City—the trouble was me. Right before the performance, “somebody” set off an M-80 in the bathroom. It was at the end of the year, everyone was about to graduate, and had all these unfortunate things not befallen me, I would have graduated, too. I was devastated. As a memento I went off with the bass drum that I played in the marching band. That drum came back to life with a haunting vengeance at the end of “Livin’ on the Edge.”

I

got sent to Jose Quintano’s School for Young Professionals, 156 West Fifty-sixth Street. It was a school for a bunch of professional brats and movie stars’ kids. There were actors, dancers, the girl who played

Annie

on Broadway, that kind of thing, but it was way more fun than Roosevelt High. Everyone there had this crazy spark to them of

fake-it-till-you-make-it-ness.

Steve Martin (same name as the comedian) was in my senior class. His full name was Steve Martin Caro. One day I asked him, “What’re you doin’ tonight?” “We’re recording,” he said. “You’re

recording

? What? Where?!” “Apostolic,” he replied. “Can I

come

?” I asked breathlessly. “Well, yeah, sure,” he said. “What’s the name of your group?” “The Left Banke,” he said. “You mean

the

Left Banke as in ‘Walk Away Renee’?” “Yeah,” he smiled. That’s when I just freaked

.

He was the lead singer of the Left Banke

.

The Left Banke were huge. Along with the Rascals and the Lovin’ Spoonful, they were the other big New York City band that had hits on the radio at that time. “What’s the song you’re going to record?” I asked. “Dunno. They give us the lead sheets when we get to the studio.” “Wait, you’re in the Left Banke, and

you don’t know what song you’re recording

?” “No, our producer tells us,” he said. I couldn’t believe it. “How the fuck can you do it?” I asked. “You don’t even know what you’re recording when you get there?”

One of the guys in the group had some Acapulco Gold. I had a thing for blondes, as all boys did, and this Acapulco chick was soon to be my new girlfriend. I got me a dime bag, which in those days came in a paper bag. A dime bag and I was on my way. We get to Apostolic Studios and it’s huge. Eighteen-foot walls, and right up at the top were the windows of the control room. I went up there to watch. I remember listening to the string section and waiting for Steve to sing. The producer and the engineers looked down at the musicians in the studio and then hit a button and over the PA they’d say, “Hey, um, will you re-sing that?” There was sheet music on a stand. I was stunned. This wasn’t like the Stones or the Yardbirds who wrote their own material, played their own stuff. They didn’t even know how to tune their instruments. The only guy in the band who had a clue about music was the keyboard player, Michael Brown. His father, Harry Lookofsky, was a session musician and he controlled everything. He was the producer and arranger, and he hired the musicians. Michael McKean, who later played David St. Hubbins—the blond dude with the meddling girlfriend in

This Is Spinal Tap

—was one of the studio musicians. Hell, I still have a problem with that movie. That woman is too close to the truth I lived (look for elaborations on that point later). I sang backup on a couple of Left Banke songs, “Dark Is the Bark” and the flip side, “My Friend Today.”

That was my introduction to recording, and I knew if they could do it, I could do it. They were

drunk

all the time, fer chrissakes. I hung out with the bass player, Tommy Finn, at his apartment. So here’s me, a kid from Yonkers, hanging out with a bunch of guys that have hit singles

and

have great pot. I was beyond impressed—I was in seventh heaven.

Hendrix had been at Apostolic not long before. God himself. “Hendrix was here two months ago . . . and he used this mic,” the engineer said. “Which one?” I begged. “This Sennheiser pencil mic.” And then, casually, he adds, “Yeah, he put it in this girl’s pussy in the bathroom. He was fuckin’ her with it!” And I went, “

Whaaattt?

Hendrix used that mic?” When the engineer turned his back, I sniffed it . . . which gave new meaning to the term

purple haze

. I guess I looked a little incredulous because he then said, “Yeah, listen to this tape! You’re not gonna believe this!” Whereupon he claps a pair of headphones to my melon and . . .

You could hear the squishing noise as Jimi inserts the mic into her gynie. And you could hear him going, “Oh, that’s

gooooood,

man, that’s cool.” And you could hear the girl moaning,

“Oh-ohhhh, ohhhhhhh, ohhh, ohhhh. . . .”

Then it shifts into an orgasmic octave higher,

“O-ohhhhhh, o-oh-oh, oh-ooooooooh!”

And he’s done. That’s when the Electric Lady’s man says (no shit), “Hey, baby, what’s your name again?” “Kathy,” she purrs. I mean, talk about urban legends. With a gearshift! I was in a new league now.

T

he Strangeurs were the opening act for every kind of gig from the Fugs at the Café Wha? to the Lovin’ Spoonful at the Westchester County Center to an uptown New York discotheque like Cheetah. Then, on July 24, 1966, the Strangeurs opened for the Beach Boys at Iona College.

Pet Sounds

had come out in May and blown everybody’s minds. It was sublime and subliminal and saturated your brain. After you heard it you were in a different space. “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” with “God Only Knows” on the flip side, had been out only a week before our performance and it was all over the radio. They had a competition to choose the band that would be the opening act. We played “Paint It Black” and sealed the deal. We got to hang out with the Beach Boys. Brian, even in those days, was on another sphere, vibrating his Buddha vibe.

I had my first out-of-body religious experience that day singing along with the Beach Boys. It was me and six thousand kids from Iona College, all singing “California Girls.”

The promoter Pete Bennett (a pretty heavy guy in the business) knew me and my bands from watching us play around New York City. And I must have been radiating that glow of

Sufi

—I know I felt like one when he was done talking to me. He asked if we wouldn’t mind opening up for the Beach Boys for the next four shows, there and around New York City. I said to him, “Let me think for a minute,” and slam-dunked him a big fat “YES!”

Through Peter Agosta we got our first recording contract. Agosta knew Bennett, who eventually became promotional manager for the Beatles at Apple and worked with Elvis, Frank Sinatra, the Stones, and Dylan. Pete Bennett arranged for us to audition for executives at Date Records, which was a division of CBS. Back in those days you brought your equipment up in the freight elevator and set up in the boardroom and played. We did a couple of numbers, and then they went and got one of their producers, Richard Gottehrer, who eventually ran Sire Records with Seymour Stein. Gottehrer offered us a deal: six thousand dollars. Okay, we’ll take it.

We did a song called “The Sun,” kind of Lennon-McCartney pop. It came out in ’66 and got a little play, but didn’t do that great here. It was a big hit in Europe: “Le Soleil,” they called it. It was about staying up all night and watching the sun come up in the morning.

It comes once a day through the shade of my window

It shines on my bed, my rug, and my floor

It shines once a day through the shade of my window

It comes once a day and not more.

It was definitely one of Don Solomon’s finest moments. The flip side was “When I Needed You,” a little harder rock, a little more experimental . . . our version of the Yardbirds. At this point we had to change our name again—CBS was concerned that our weird spelling, the Strangeurs, wasn’t different enough from the other Strangers and we might get sued. So we became the Chain Reaction, which is a continuous, unstoppable flow of energy.

During this time, I moved out of my house in Yonkers to West Twenty-first Street, the only blue building on the block. There I lived with Lynn Collins, a gorgeous blonde whom I stole away from my guitar player, Marvin Patacki. In ’69 I saw Zeppelin at the Tea Party. When the band came offstage, I went back to say hello to the guys, ’cause Henry Smith was working for Bonzo, and who do you think comes walking out of the dressing room on Jimmy Page’s arm? Lynn Collins. She was a genuine, high-class girl-about-rock-’n’-roll-town. I thought to myself, “If I was gonna lose her, might as well be to a legend like Page.”

Eventually, Henry became our first roadie (whom we could pay), and because he lived in Westport, Connecticut, a richer side of the tracks than I came from, he could get us better-class gigs. Henry would book the Chain Reaction into these gigs we could have never booked ourselves, like opening for Sly and the Family Stone, opening for the Byrds, and the coup de grâce, opening for the Yardbirds. Jimmy Page was on bass, Jeff Beck was on lead guitar, and we were in seventh heaven. We drove up in my mother’s station wagon with our equipment. The Yardbirds had a van. We pulled out our gear and put it on the sidewalk while they took theirs out. They had some fantastic equipment, so I made this little joke, like “Let’s not get it mixed up.” I saw Jimmy Page struggling with his amp and I said, “I’ll help you with that.” Hence: “I was a roadie for the Yardbirds.” At least it gave me something to talk about while Aerosmith was getting its wings in the early days.

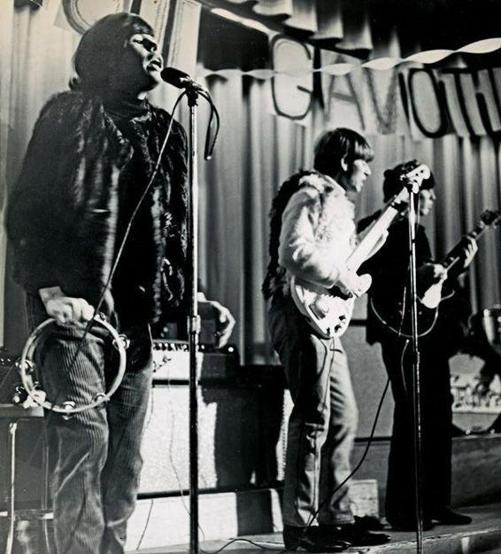

T

he Chain Reaction opening up for The Byrds in 1967 at County Court, Yonkers, White Plains, New York. Me, Alan Stohmayer, and Peter Stahl. (Not pictured: Barry Shapiro and Don Solomon.) (Ernie Tallarico)

Oddly enough, three years later, Henry Smith, still working for us as a full-time roadie this time, gets a phone call from his old-time buddy Brad Condliff at the front door to the club in Greenwich Village called Salvation, asking Henry if he wanted to help out his old buddy Jimmy Page with his recently formed band, the New Yardbirds (always respect the guy at the door). Henry grabbed a ticket to London and his only possession at that time, a large toolbox covered with stickers with only enough room for a pair of underwear, which he stuffed in behind his ounce of pot, and headed off to Europe to help his friend with this new band that over that summer became Led Zeppelin.

Everybody likes to overblow their past, including me—to squeeze out the relevance of what may or may not have really taken place. And when you’re just starting out, any story will do. Beck was on guitar, Jimmy Page on bass—it was the Yardbirds’ second incarnation (after Eric Clapton left), an unbelievable, unstoppable, funky, overamped R&B machine. “Train Kept a-Rollin’ ” was bone-rattling . . . there was steam and flames coming out of it, and the whole place quaked like a Mississippi boxcar on methadrine.

Every morning before school I’d fill a plastic cup with Dewar’s whiskey or vodka and down it. I used to dry my hair before school to “Think About It,” the last single the Yardbirds did. I’d get the vacuum cleaner, take the hose, and stick it in the exhaust socket so it blew out . . . turn it on, go upstairs, and eat breakfast. By the time I got back downstairs, the vacuum cleaner was warm and I could blow-dry my wet hair to look like a Brian Jones bubblehead. Got to have good

ha-air

! I used to sew buttons to the sides of my cowboy boots, and at the bottom of the inside leg of my pants I would tie three or four loops of dental floss and attach those to the buttons on the boots so that my pants would never ride up. I loved doing that sort of thing! I was a rabid rock fashion dog. So I went to school, spending an hour getting ready every morning, and ended up getting shit for it. I wound up in the principal’s office every day. “Tallarico, you look like a girl,” the man would say. I’d tried to explain, “It’s part of my

job

. . . rock musician, sir.” That got me absolutely nowhere.

From winter ’66 into spring ’67, Chain Reaction continued to get good gigs—in part through Pete Bennett. We played record hops with the WMCA Good Guys. We opened for the Left Banke, the Soul Survivors, the Shangri-Las, Leslie West and the Vagrants, Jay and the Americans, and Frank Sinatra, Jr. Little Richard emceed one of our shows—the original possessed character always doing that crazy shit. He was so fucking out there. He could get so high and still function. I don’t know how the fuck he did it! He was doing amyl nitrate. That’s scary stuff. There aren’t a lot of drugs I’ve refused, but with that shit I was, like, “I’m outta here!”

Pete Bennett wanted to get rid of the band and just represent me, but I wouldn’t do it, even though Chain Reaction was already winding down. After three years I’d definitely had it with covering Beatles tunes. I was already thinking about a hard rock band. Our last gig was at the Brooklawn Country Club in Connecticut on June 18, 1967. We made one more single, which came out on Verve the following year: “You Should Have Been Here Yesterday” and “Ever Lovin’ Man.” And that was that—the Chain stopped a-rollin’.