Domes of Fire (2 page)

Authors: David Eddings

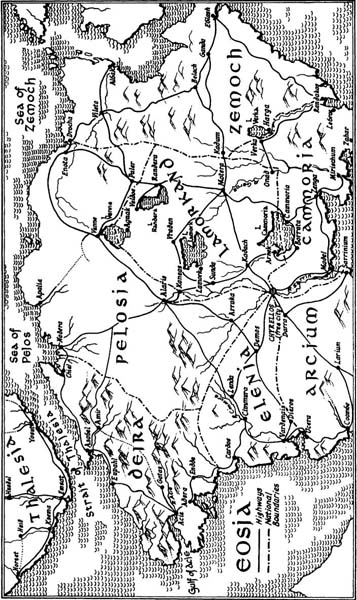

As the situation reached crisis proportions, help arrived for the beleaguered defenders in the form of the armies of the western Elene kingdoms. (Elene politics, one notes, are quite robust.) The connection between the Primate of Cimmura and the renegade Martel came to light as well as the fact that the pair had a subterranean arrangement with Otha of Zemoch. Outraged by the perfidy of the man, the Hierocracy rejected his candidacy and elected instead one Dolmant, the Patriarch of Demos. This Dolmant appears to be competent, though it may be too early to say for certain.

Queen Ehlana of the Kingdom of Elenia was scarcely more than a child, but she appeared to be a strong-willed and spirited young woman. She had long had a secret preference for Sir Sparhawk, though he was more than twenty years her senior; and upon her recovery it had been announced that the two were betrothed. Following the election of Dolmant to the Archprelacy, they were wed. Peculiarly enough, the queen retained her authority, although we must suspect that Sir Sparhawk exerts considerable influence upon her in state as well as domestic matters.

The involvement of the Emperor of Zemoch in the internal affairs of the Elene Church was, of course, a

casus belli,

and the armies of western Eosia, led by the Church Knights, marched eastward across Lamorkand to meet the Zemoch hordes poised on the border. The long-dreaded Second Zemoch War had begun.

Sir Sparhawk and his companions, however, rode

north to avoid the turmoil of the battlefield, and they then turned eastward, crossed the mountains of northern Zemoch and surreptitiously made their way to Otha’s capital at the city of Zemoch, evidently in pursuit of Annias and Martel.

The best efforts of the empire’s agents in the west have failed to reveal precisely what took place at Zemoch. It is quite certain that Annias, Martel and Otha himself perished there, but they are of little note in the pageant of history. What is far more relevant is the incontrovertible fact that Azash, Elder God of Styricum and the driving force behind Otha and his Zemochs,

also

perished, and it is undeniably true that Sir Sparhawk was responsible. We must concede that the levels of magic unleashed at Zemoch were beyond our comprehension and that Sir Sparhawk has powers at his command such as no mortal has ever possessed. As evidence of the levels of violence unleashed in the confrontation, we need only point to the fact that the city of Zemoch was utterly destroyed during the discussions.

Clearly, Zalasta the Styric had been right. Sir Sparhawk, the prince consort of Queen Ehlana, was the one man in all the world capable of dealing with the crisis in Tamuli. Unfortunately, Sir Sparhawk was not a citizen of the Tamul Empire, and thus could not be summoned to the imperial capital at Matherion by the emperor. His Majesty’s government was in a quandary. The emperor had no authority over this Sparhawk, and to have been obliged to appeal to a man who was essentially a private citizen would have been an unthinkable humiliation.

The situation in the empire was daily worsening, and our need for the intervention of Sir Sparhawk was growing more and more urgent. Of equal urgency was the absolute necessity of maintaining the empire’s dignity.

It was ultimately the Foreign Office’s most brilliant diplomat, First Secretary Oscagne, who devised a solution to the dilemma. We will discuss his Excellency’s brilliant diplomatic ploy at greater length in the following chapter.

It was early spring, and the rain still had the lingering chill of winter. A soft, silvery drizzle sifted down out of the night sky and wreathed around the blocky watchtowers of Cimmura, hissing in the torches on each side of the broad gate and making the stones of the road leading up to the gate shiny and black. A lone rider approached the city. He was wrapped in a heavy traveller’s cloak and rode a tall, shaggy roan horse with a long nose and flat, vicious eyes. The traveller was a big man, a bigness of large, heavy bone and ropy tendon rather than of flesh. His hair was coarse and black, and at some time his nose had been broken. He rode easily but with the peculiar alertness of the trained warrior.

The big roan shuddered absently, shaking the rain out of his shaggy coat as they approached the east gate of the city and stopped in the ruddy circle of torchlight just outside the wall.

An unshaven gate guard in a rust-splotched breastplate and helmet and with a patched green cloak hanging negligently from one shoulder came out of the gate house to look inquiringly at the traveller. He was swaying slightly on his feet.

‘Just passing through, neighbour,’ the big man said in a quiet voice. He pushed back the hood of his cloak.

‘Oh,’ the guard said, ‘it’s you, Prince Sparhawk. I didn’t recognise you. Welcome home.’

‘Thank you,’ Sparhawk replied. He could smell the cheap wine on the man’s breath.

‘Would you like to have me send word to the palace that you’ve arrived, your Highness?’

‘No. Don’t bother them. I can unsaddle my own horse.’ Sparhawk privately disliked ceremonies – particularly late at night. He leaned over and handed the guard a small coin. ‘Go back inside, neighbour. You’ll catch cold if you stand out here in the rain.’ He nudged his horse and rode on through the gate.

The district near the city wall was poor, with shabby, run-down houses standing tightly packed beside each other, their second storeys projecting out over the wet littered streets. Sparhawk rode up a narrow, cobbled street with the slow clatter of the big roan’s steel-shod hooves echoing back from the buildings. The night breeze had come up, and the crude signs identifying this or that tightly-shuttered shop on the street-level floors swung creaking on rusty hooks.

A dog with nothing better to do came out of an alley to bark at them with brainless self-importance. Sparhawk’s horse turned his head slightly to give the wet cur a long, level stare that spoke eloquently of death. The empty-headed dog’s barking trailed off and he cringed back, his rat-like tail between his legs. The horse bore down on him purposefully. The dog whined, then yelped, turned and fled. Sparhawk’s horse snorted derisively.

‘That make you feel better, Faran?’ Sparhawk asked the roan.

Faran flicked his ears.

‘Shall we proceed then?’

A torch burned fitfully at an intersection, and a buxom young whore in a cheap dress stood, wet and bedraggled, in its ruddy, flaring light. Her dark hair was plastered to her head, the rouge on her cheeks was streaked and she had a resigned expression on her face.

‘What are you doing out here in the rain, Naween?’ Sparhawk asked her, reining in his horse.

‘I’ve been waiting for you, Sparhawk.’ Her tone was arch, and her dark eyes wicked.

‘Or for anyone else?’

‘Of course. I

am

a professional, Sparhawk, but I still owe you. Shouldn’t we settle up one of these days?’

He ignored that. ‘What are you doing working the streets?’

‘Shanda and I had a fight,’ she shrugged. ‘I decided to go into business for myself.’

‘You’re not vicious enough to be a street-girl, Naween.’ He dipped his fingers into the pouch at his side, fished out several coins and gave them to her. ‘Here,’ he instructed. ‘Get a room in an inn someplace and stay off the streets for a few days. I’ll talk with Platime, and we’ll see if we can make some arrangements for you.’

Her eyes narrowed. ‘You don’t have to do that, Sparhawk. I can take care of myself.’

‘Of

course

you can. That’s why you’re standing out here in the rain. Just do it Naween. It’s too late and too wet for arguments.’

‘This is two I owe you, Sparhawk. Are you absolutely sure…?’ She left it hanging.

‘Quite sure, little sister. I’m married now, remember?’

‘So?’

‘Never mind. Get in out of the weather.’ Sparhawk rode on, shaking his head. He liked Naween, but she was hopelessly incapable of taking care of herself.

He passed through a quiet square where all the shops and booths were shut down. There were few people abroad tonight, and few business opportunities. He let his mind drift back over the past month and a half. No one in Lamorkand had been willing to talk with him. Archprelate Dolmant was a wise man, learned in doctrine and Church politics, but he was woefully ignorant of the way the common people thought. Sparhawk had

patiently tried to explain to him that sending a Church Knight out to gather information was a waste of time, but Dolmant had insisted, and Sparhawk’s oath obliged him to obey. And so it was that he had wasted six weeks in the ugly cities of southern Lamorkand where no one had been willing to talk with him about anything more serious than the weather. To make matters even worse, Dolmant had quite obviously blamed the knight for his own blunder.

In a dark side-street where the water dripped monotonously onto the cobblestones from the eaves of the houses, he felt Faran’s muscles tense. ‘Sorry,’ he said quietly. ‘I wasn’t paying attention.’ Someone was watching him, and he could clearly sense the animosity which had alerted his horse. Faran was a war-horse, and he could probably sense antagonism in his veins. Sparhawk muttered a quick spell in the Styric tongue, concealing the gestures which accompanied it beneath his cloak. He released the spell slowly to avoid alerting whoever was watching him.

The watcher was not an Elene. Sparhawk sensed that immediately. He probed further. Then he frowned. There were more than one, and they were not Styrics either. He pulled his thought back, passively waiting for some clue as to their identity.

The realisation came as a chilling shock. The watchers were not human. He shifted slightly in his saddle, sliding his hand toward his sword-hilt.

Then the sense of the watchers was gone, and Faran shuddered with relief. He turned his ugly face to give his master a suspicious look.

‘Don’t ask me, Faran,’ Sparhawk told him. ‘I don’t know either.’ But that was not entirely true. The touch of the minds in the darkness had been vaguely familiar, and that familiarity had raised questions in Sparhawk’s mind, questions he did not want to face.

He paused at the palace gate long enough to firmly instruct the soldiers not to wake the whole house, and then he dismounted in the courtyard.

A young man stepped out into the rain-swept yard from the stable. ‘Why didn’t you send word that you were coming, Sparhawk?’ he asked very quietly.

‘Because I don’t particularly like parades and wild celebrations in the middle of the night,’ Sparhawk told his squire, throwing back the hood of his cloak. ‘What are you doing up so late? I promised your mothers I’d make sure you got your rest. You’re going to get me in trouble, Khalad.’

‘Are you trying to be funny?’ Khalad’s voice was gruff, abrasive. He took Faran’s reins. ‘Come inside, Sparhawk. You’ll rust if you stand out here in the rain.’

‘You’re as bad as your father was.’

‘It’s an old family trait.’ Khalad led the prince consort and his evil-tempered warhorse into the hay-smelling stable where a pair of lanterns gave off a golden light. Khalad was a husky young man with coarse black hair and a short-trimmed black beard. He wore tight-fitting black leather breeches, boots and a sleeveless leather vest that left his arms and shoulders bare. A heavy dagger hung from his belt, and steel cuffs encircled his wrists. He looked and behaved so much like his father that Sparhawk felt again a brief, brief pang of loss. ‘I thought Talen would be coming back with you,’ Sparhawk’s squire said as he began unsaddling Faran.

‘He’s got a cold. His mother – and yours – decided that he shouldn’t go out in the weather, and

I

certainly wasn’t going to argue with them.’

‘Wise decision,’ Khalad said, absently slapping Faran on the nose as the big roan tried to bite him. ‘How are they?’

‘Your mothers? Fine. Aslade’s still trying to fatten Elys

up, but she’s not having too much luck. How did you find out I was in town?’

‘One of Platime’s cut-throats saw you coming through the gate. He sent word.’

‘I suppose I should have known. You didn’t wake my wife, did you?’

‘Not with Mirtai standing watch outside her door, I didn’t. Give me that wet cloak, my Lord. I’ll hang it in the kitchen to dry.’

Sparhawk grunted and removed his sodden cloak.

‘The mail shirt too, Sparhawk,’ Khalad added, ‘before it rusts away entirely.’

Sparhawk nodded, unbelted his sword and began to struggle out of his chain-mail shirt. ‘How’s your training going?’

Khalad made an indelicate sound. ‘I haven’t learned anything I didn’t already know. My father was a much better instructor than the ones at the chapterhouse. This idea of yours isn’t going to work, Sparhawk. The other novices are all aristocrats, and when my brothers and I outstrip them on the practice field, they resent it. We make enemies every time we turn around.’ He lifted the saddle from Faran’s back and put it on the rail of a nearby stall. He briefly laid his hand on the big roan’s back, then bent, picked up a handful of straw and began to rub him down.

‘Wake some groom and have him do that,’ Sparhawk told him. ‘Is anybody still awake in the kitchen?’

‘The bakers are already up, I think.’

‘Have one of them throw something together for me to eat. It’s been a long time since lunch.’

‘All right. What took you so long in Chyrellos?’

‘I took a little side trip into Lamorkand. The civil war there’s getting out of hand, and the Archprelate wanted me to nose around a bit.’

‘You should have got word to your wife. She was just

about to send Mirtai out to find you.’ Khalad grinned at him. ‘I think you’re going to get yelled at again, Sparhawk.’

‘There’s nothing new about that. Is Kalten here in the palace?’

Khalad nodded. ‘The food’s better here, and he isn’t expected to pray three times a day. Besides, I think he’s got his eye on one of the chambermaids.’

‘That wouldn’t surprise me very much. Is Stragen here too?’

‘No. Something came up, and he had to go back to Emsat.’

‘Get Kalten up then. Have him join us in the kitchen. I want to talk with him. I’ll be along in a bit. I’m going to the bathhouse first.’

‘The water won’t be warm. They let the fires go out at night.’

‘We’re soldiers of God, Khalad. We’re all supposed to be unspeakably brave.’

‘I’ll try to remember that, my Lord.’

The water in the bathhouse was definitely on the chilly side, so Sparhawk did not linger very long. He wrapped himself in a soft white robe and went into the dim corridors of the palace and to the brightly-lit kitchens where Khalad waited with the sleepy-looking Kalten.

‘Hail, Noble Prince Consort,’ Kalten said drily. Sir Kalten obviously didn’t care much for the idea of being roused in the middle of the night.

‘Hail, Noble Boyhood Companion of the Noble Prince Consort,’ Sparhawk replied.

‘Now there’s a cumbersome title,’ Kalten said sourly. ‘What’s so important that it won’t wait until morning?’

Sparhawk sat down at one of the work tables, and a white-smocked baker brought him a plate of roast beef and a steaming loaf still hot from the oven.

‘Thanks, neighbour,’ Sparhawk said to him.

‘Where have you been, Sparhawk?’ Kalten demanded, sitting down across the table from his friend. Kalten had a wine flagon in one hand and a tin cup in the other.

‘Sarathi sent me to Lamorkand,’ Sparhawk replied, tearing a chunk of bread from the loaf.

‘Your wife’s been making life miserable for everyone in the palace, you know.’

‘It’s nice to know she cares.’

‘Not for any of the rest of us it isn’t. What did Dolmant need from Lamorkand?’

‘Information. He didn’t altogether believe some of the reports he’s been getting.’

‘What’s not to believe? The Lamorks are just engaging in their national pastime – civil war.’

‘There seems to be something a little different this time. Do you remember Count Gerrich?’

‘The one who had us besieged in Baron Alstrom’s castle? I never met him personally, but his name’s sort of familiar.’

‘He seems to be coming out on top in the squabbles in western Lamorkand, and most everybody up there believes that he’s got his eye on the throne.’

‘So?’ Kalten helped himself to part of Sparhawk’s loaf of bread. ‘Every baron in Lamorkand has his eyes on the throne. What’s got Dolmant so concerned about it this time?’

‘Gerrich’s been making alliances beyond the borders of Lamorkand. Some of those border barons in Pelosia are more or less independent of King Soros.’

‘Everybody in Pelosia’s independent of Soros. He isn’t much of a king. He spends too much time praying.’

‘That’s a strange position for a soldier of God,’ Khalad murmured.

‘You’ve got to keep these things in perspective,

Khalad,’ Kalten told him. ‘Too much praying softens a man’s brains.’

‘Anyway,’ Sparhawk went on. ‘If Gerrich succeeds in dragging those Pelosian barons into his bid for King Friedahl’s throne, Friedahl’s going to have to declare war on Pelosia. The Church already has a war going on in Rendor, and Dolmant’s not very enthusiastic about a second front.’ He paused. ‘I ran across something else, though,’ he added. ‘I overheard a conversation I wasn’t supposed to. The name Drychtnath came up. Do you know anything about him?’

Kalten shrugged. ‘He was the national hero of the Lamorks some three or four thousand years ago. They say he was about twelve feet tall, ate an ox for breakfast every morning and drank a hogshead of mead every evening. The story has it that he could shatter rocks by scowling at them and reach up and stop the sun with one hand. The stories might be just a little bit exaggerated, though.’