Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (3 page)

Read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Nonfiction, #Biography, #History

“Christ,” mutters Dad.

Mum has sung “Olé, I Am a Bandit” at every bar under the southern African sun in which she has ever stepped.

“Shut your mother up, will you?” says Dad, climbing out of the pickup with a fistful of passports and papers, “eh?”

I go around the back. “Shhhh! Mum! Hey, Mum, we’re at the border now. Shhh!”

She emerges blearily from the folds of the tarpaulin. “I’m the quickest on the trigger,” she sings loudly.

“Oh, great.” I ease back into the front of the pickup and light a cigarette. I’ve been shot at before because of Mum and her singing. She made me drive her to our neighbor’s once at two in the morning to sing them “Olé, I Am a Bandit,” and he pulled a rifle on us and fired. He’s Yugoslav.

The customs official comes out to inspect our vehicle. I grin rabidly at him.

He circles the car, stiff-legged like a dog wondering which tire to pee on. He swings his AK-47 around like a tennis racket.

“Get out,” he tells me.

I get out.

Dad gets uneasy. He says, “Steady on with the stick, hey?”

“What?”

Dad shrugs, lights a cigarette. “Can’t you keep your bloody gun still?”

The official lets his barrel fall into line with Dad’s heart.

Mum appears from under the drapes of the tarpaulin again. Her half-mast eyes light up.

“Muli bwanje?”

she says elaborately: How are you?

The customs official blinks at her in surprise. He lets his gun relax against his hip. A smile plays around his lips. “Your wife?” he asks Dad.

Dad nods, smokes. I crush out my cigarette. We’re both hoping Mum doesn’t say anything to get us shot.

But her mouth splits into an exaggerated smile, rows of teeth. She nods toward Dad and me:

“Kodi ndipite ndi taxi?”

she asks: Should I take a taxi?

The customs official leans against his gun for support (hand over the top of the barrel) and laughs, throwing back his head.

Mum laughs, too. Like a small hyena, “Hee-hee,” wheezing a bit from all the dust she has inhaled today. She has a dust mustache, dust rings around her eyes, dust where forehead joins hairline.

“Look,” says Dad to the customs official, “can we get going? I have to get my daughter to school today.”

The customs official turns suddenly businesslike. “Ah,” he says, his voice threatening hours of delay, if he likes, “where is my gift?” He turns to me. “Little sister? What have you brought for me today?”

Mum says, “You can have her, if you like,” and disappears under her tarpaulin. “Hee, hee.”

“Cigarettes?” I offer.

Dad mutters, “Bloody—“ and swallows the rest of his words. He climbs into the pickup and lights a cigarette, staring fixedly ahead.

The customs official eventually opens the gate when he is in possession of one box of Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes (mine, intended for school), a bar of Palmolive soap (also intended for school), three hundred kwacha, and a bottle of Coke.

As we bump onto the bridge that spans the Zambezi River, Dad and I hang out of our windows, scanning the water for hippo.

Mum has reemerged from the tarpaulin to sing, “Happy, happy Africa.”

If I weren’t going back to school, I would be in heaven.

Kelvin

CHIMURENGA I:

ZAMBIA, 1999

“Look,” Mum says, leaning across the table and pointing. Her finger is worn, blunt with work: years of digging in a garden, horses, cows, cattle, woodwork, tobacco. “Look, we fought to keep

one

country in Africa white-run”—she stops pointing her finger at our surprised guest to take another swallow of wine—“just one country.” Now she slumps back in defeat: “We lost twice.”

The guest is polite, a nice Englishman. He has come to Zambia to show Africans how to run state-owned businesses to make them attractive to foreign investment, now that we aren’t Social Humanists anymore. Now that we’re a democracy.

Ha ha.

Kind of.

Mum says, “If we could have kept one country white-ruled it would be an oasis, a refuge. I mean, look what a cock-up. Everywhere you look it’s a bloody cock-up.”

The guest says nothing, but his smile is bemused. I can tell he’s thinking,

Oh my God, they’ll never believe this when I tell them back home.

He’s saving this conversation for later. He’s a two-year wonder. People like this never last beyond two malaria seasons, at most. Then he’ll go back to England and say, “When I was in Zambia . . .” for the rest of his life.

“Good dinner, Tub,” says Dad.

Mum did not cook the dinner. Kelvin cooked the dinner. But Mum

organized

Kelvin.

Dad lights an after-dinner pipe and smokes quietly. He is leaning back in his chair so that there is room on his lap for his dog between his slim belly and the table. He stares out at the garden. The sun has set in a red ball, sinking behind the quiet, stretching black limbs of the msasa trees on Oribi Ridge, which is where my parents moved after I was married. The dining room has only three walls: it lies open to the bush, to the cries of the night insects, the shrieks of the small, hunted animals, the bats which flit in and out of the dining room, swooping above our heads to eat mosquitoes. Clinging to the rough whitewashed cement walls are assorted moths, lizards, and geckos, which occasionally let go with a high, sharp laugh: “He-he-he.”

Mum pours herself more wine, finishing the bottle, and then she says fiercely to our guest, “Thirteen thousand Kenyans and a hundred white settlers died in the struggle for Kenya’s independence.”

I can tell the visitor doesn’t know if he should look impressed or distressed. He settles for a look of vague surprise. “I had no idea.”

“Of course you bloody people had no idea,” says Mum. “A hundred . . . of us.”

“Cool it, Tub,” says Dad, stroking the dog and smoking.

“Nineteen forty-seven to nineteen sixty-three,” says Mum. “Nearly twenty bloody years we tried to hold on.” She makes her fist into a tight grip. The sinews on her neck stand taut and she bares her teeth. “All for what? And what a cock-up they’ve made of it now. Hey? Bloody, bloody cock-up.”

After independence, Kenya was run by Mzee, the Grand Old Man, Jomo Kenyatta. He had been born in 1894, the year before Britain declared Kenya one of its protectorates. He had come to power in 1963, an old man who had finally fulfilled the destiny of his life’s work: self-government for Africans in Africa.

Dad says, mildly, “Shall I ask Kelvin to clear the table?”

Mum says, “And Rhodesia. One thousand government troops dead.” She pauses. “Fourteen thousand terrorists. We should have won, if you look at it like that, except there were more of them.” Mum drinks, licks her top lip. “Of course, we couldn’t stay on in Kenya after Mau Mau.” She shakes her head.

Kelvin comes to clear the table. He is trying to save enough money, through the wages he earns as Mum and Dad’s housekeeper, to open his own electrical shop.

Mum says, “Thank you, Kelvin.”

Kelvin almost died today. Irritated to distraction by the flies in the kitchen, he had closed the two doors and the one little window in the room, into which he had then emptied an entire can of insect-killing Doom. Mum had found him convulsing on the kitchen floor just before afternoon tea.

“Bloody idiot.” She had dragged him onto the lawn, where he lay jerking and twitching for some minutes until Mum sloshed a bucket of cold water onto his face. “Idiot!” she shrieked. “You could have killed yourself.”

Now Kelvin looks as self-possessed and serene as ever. Jesus, he has told me, is his Savior. He has an infant son named Elvis, after the other King.

Dad says, “Bring more beers, Kelvin.”

“Yes, Bwana.”

We move to the picnic chairs around the wood fire on the veranda. Kelvin brings us more beers and clears the rest of the plates away. I light a cigarette and prop my feet up on the cold end of a burning log.

“I thought you quit,” says Dad.

“I did.” I throw my head back and watch the light-gray smoke I exhale against black sky, the bright cherry at the tip of my cigarette against deep forever. The stars are silver tubes of light going back endlessly, years and light-years into themselves. The wind shifts restlessly. Maybe it will rain in a week or so. Wood smoke curls itself around my shoulders, lingers long enough to scent my hair and skin, and then veers toward Dad. The two of us are silent, listening to Mum and her stuck record,

Tragedies of Our Lives.

What the patient, nice Englishman does not know, which Dad and I both know, is that Mum is only on Chapter One.

Chapter One: The War

Chapter Two: Dead Children

Chapter Three: Insanity

Chapter Four: Being Nicola Fuller of Central Africa

Chapter Four is really a subchapter of the other chapters. Chapter Four is when Mum sits quietly, having drunk so much that every pore in her body is soaked. She is yoga-cross-legged, and she stares, with a look of stupefied wonder, at the garden and at the dawn breaking through wood-smoke haze and the thin gray-brown band of dust and pollution that hangs above the city of Lusaka. And she’s thinking,

So this is what it’s like being Me.

Kelvin comes. “Good night.”

Mum is already sitting yoga-cross-legged, cradling a drink on her lap. “Good night, Kelvin,” she says with great emphasis, almost with respect (a sad, dignified respect). As if he were dead and she were throwing the first clump of soil onto his coffin.

Dad and I excuse ourselves, gather a collection of dogs, and make for our separate bedrooms, leaving Mum, the Englishman, and two swooping bats in the company of the sinking fire. The Englishman, who spent much of supper

warily eyeing the bats and ducking every time one flitted over the table, has now got beyond worrying about bats.

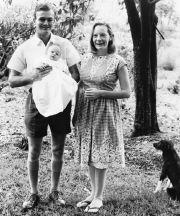

Mum, Dad, Van—Kenya

Guests trapped by Mum have Chapters of their own.

Chapter One: Delight

Chapter Two: Mild Intoxication Coupled with Growing Disbelief

Chapter Three: Extreme Intoxication Coupled with Growing Panic

Chapter Four: Lack of Consciousness

I am here visiting from America. Smoking cigarettes when I shouldn’t be. Drinking carelessly under a huge African sky. So happy to be home I feel as if I’m swimming in syrup. My bed is closest to the window. The orange light from the dying fire glows against my bedroom wall. The bedding is sweet-bitter with wood smoke. The dogs wrestle for position on the bed. The old, toothless spaniel on the pillow, one Jack Russell at each foot.

“Rhodesia was run by a white man, Ian Douglas Smith, remember him?”

“Of course,” says the unfortunate captive guest, now too drunk to negotiate the steep, dusty driveway through the thick, black-barked trees to the long, red-powdered road that leads back to the city of Lusaka, where he has a nice, European-style house with an ex–embassy servant and a watchman (complete with trained German shepherd). Now, instead of going back to his guarded African-city suburbia, he will sit up until dawn, drinking with Mum.

“He came to power in 1964. On the eleventh of November, 1965, he made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain. He made it clear that there would never be majority rule in Rhodesia.” Even when Mum is so drunk that she is practicing her yoga moves, she can remember the key dates relating to Our Tragedies.

“So we moved there in 1966. Our daughter—Vanessa, our eldest—was only one year old. We were prepared”—Mum’s voice grows suitably dramatic—“to take our baby into a war to live in a country where white men still ruled.”

Bumi, the spaniel, tucks her chin onto the pillow next to my head, where she grunts with content before she begins to snore. She has dead-rabbit breath. I turn over, my face away from hers, and go to sleep.

The last thing I hear is Mum say, “We were prepared to die, you see, to keep one country white-run.”

In the morning Mum is Chapter Four, smiling idiotically to herself, a warm, flat beer propped between her thighs, her head cockeyed. She is staring damply into the pink-yellow dawn. The guest is Chapter Four too, lying grayly on the lawn. He isn’t convulsing, but in almost every other respect, he looks astonishingly like Kelvin did yesterday afternoon.

Kelvin has brought the tea and is laying the table for breakfast As If Everything Were Normal.

Which it is. For us.