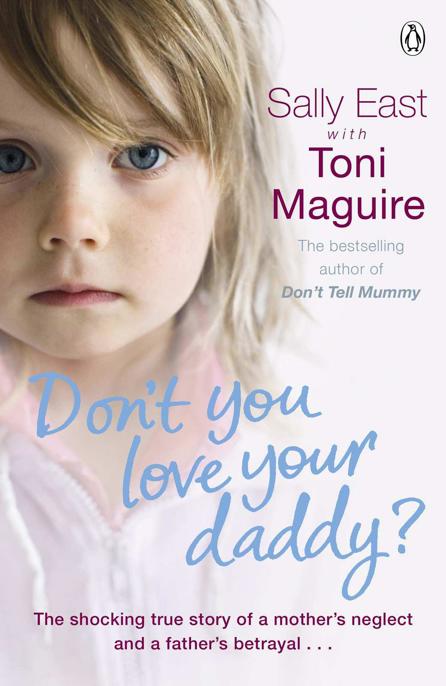

Don't You Love Your Daddy?

Read Don't You Love Your Daddy? Online

Authors: Sally East

SALLY EAST WITH

TONI MAGUIRE

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London

WC2R 0RL

, England

First published 2010

Copyright © Sally East and Toni Maguire, 2010

All rights reserved

The moral right of the authors has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN:

978-0-14-196393-8

I have never visited my father’s grave. I know where it is, of course, for when he died I had received a phone call inviting me to his funeral. An invitation I chose to ignore – I had no need to say my final goodbyes: they had been said a long time before.

Over the years since I learnt of his death I have tried to erase all memories of him from my thoughts, but still they slither unwanted into my mind – as does the image of the small blonde-haired, green-eyed child who once was me.

I see her when, scarcely older than a toddler, she loved her tall, handsome, dark-haired father. When, returning from his work as a carpenter, he bounced into the house with a wide smile that she thought was just for her, she would stretch her arms towards him, her face alight with joy at his return. Even before her chubby little hands received the sweets or bars of chocolate that she knew he would have hidden in his jacket pocket especially for her, she would demand his immediate attention. ‘Up, Daddy, uppy!’ she would urge him.

And, laughing at her determination, he would sweep her up from the floor and swing her into the air. I can still hear his voice murmuring, ‘You’re my own special little girl, aren’t you, Sally?’ Her arms would wind around his neck – she liked the feel of him holding her. She enjoyed inhaling his particular aroma, one of newly sawed timber, wood varnish, cigarettes and aftershave that clung to his skin, hair and clothes. With his rough cheek pressed to hers, she snuggled against his chest.

‘Don’t you love your daddy?’ he would ask, and always received a fast succession of nods in reply. ‘Well, say it, then!’ he would demand, and obediently she would utter the words he wanted to hear.

‘I love you, Daddy.’

That was before she began to fear him.

The first seven years of my life were spent in a northern English village where, from spring to late autumn, children played in the streets and women stood outside shops or leant over garden fences chatting. When October, with its thin drizzling rain, gave way to November, iron-grey clouds released sheets of rain, hail and sleet. Then we hurried back to our houses and scuttled inside for warmth. During the months before spring arrived, the dark streets were almost deserted as people huddled inside their homes. The flickering lights of televisions shone out of dim rooms and fell on the bare branches of trees, while soggy clumps of fallen leaves drifted in the gutters. Early evening brought the sound of slamming doors, which announced the men returning from work. Their battered old cars lined the streets, for in the country, apart from a daily bus, they were the only means of transport other than bicycles.

The house I was born into was a three-bedroom terrace in the middle of a council estate that lay on the edge of our village. My mother told me that when, ten years before I was born, my parents had moved in, the houses smelt of new paint and recently dried plaster. The small gardens, bisected by a short concrete path, were freshly dug farm soil: no grass had been laid, no shrubs or flowers planted.

For many of the young couples who had been handed a front-door key, it was their first home; they had lived with parents or in-laws while they waited for a council house to become available. But the one thing that every family moving on to the new estate shared was optimism.

By the time I was old enough to notice the difference between our house and the others on the estate, the years of neglect had taken their toll. Paint had peeled off the window and door frames, and while our neighbours’ gardens had been lovingly nurtured, ours was overgrown with coarse grass and dead bushes. The wind brought seeds that took root sometimes, but finally withered and died.

Apart from the times when my mother seemed to have unlimited energy, our curtains hung drably from the windows, while in the backyard damp washing, which often she left out for days, flapped on a sagging rope clothes-line.

My elder brother, Pete, was a baby of only a few months when they moved in, but by the time I was old enough to know him, he was an angry teenager who avoided his home and, it appeared, me too.

My father’s family, which consisted of three brothers, their wives and children, his unmarried sister and my grandparents, all lived in the village, and as a small child I always had my cousins of various ages to play with. My mother had only one sister, Janet, who lived nearly a hundred miles away. I don’t remember my maternal grandparents, who were already middle-aged when their two daughters were born, as they had died when I was just a baby.

Every Sunday our whole family would meet at the church, the men in dark suits and the women wearing matching Crimplene dresses and jackets, with an assortment of hats, while the children had on their Sunday best. Young boys wore short trousers, crisp white shirts, their school ties and blazers, and their hair was combed neatly into place. The girls were smart in skirts, blouses and jumpers. I can remember that I wore, depending on the season, either a plaid dress or a pink cotton one, with short white lacy socks and black patent shoes; Pete wore long grey flannel trousers and a dark blue blazer.

When my mother came to church dressed in something long and floaty made of brightly coloured Indian cotton, she looked different from the other women. With her shiny shoulder-length blonde hair uncovered, her porcelain skin and slender figure, I thought she was the prettiest mother there. I liked it when she was beside me in church, her hand wrapped around my smaller one, and I felt something akin to shame for her when she failed to make an appearance. ‘Too tired,’ was one of her excuses or ‘Not feeling well,’ and before we left the house without her I would see my father’s face tighten with barely concealed rage.

‘What do you think it looks like you not being there?’ he would ask, but she only shrugged and muttered that she didn’t really care.

‘Your mother will give you all your Sunday lunch,’ she said, in a faraway voice. ‘She likes to do that.’ My father would stomp out of the house, with me and Pete following anxiously behind him.

When the assembled family saw that, once again, my mother had not come with us, there was an exasperated sigh from my stern grandfather and tutting from my grandmother who, with my aunts, uncles and cousins, were impatiently waiting on the church steps for us to arrive.

My grandmother’s hand would rest briefly on my shoulder to show it was not me she was angry with, before we all trooped inside to take our places.

Too young to read the hymns I had managed to learn the words of the most popular ones and sang along enthusiastically. I loved the beauty of the church, with its high arches and stained-glass windows, the pure sounds of the organ and the choir, but I was always bored by the sermon. It made little sense to me and just seemed to go on and on. I tried not to fidget but it was hard to sit still, and Pete also appeared bored and tried to make me giggle by pulling funny faces. If my father saw him and glared, he would cast his eyes down and slouch on the pew.