Down & Dirty (26 page)

Authors: Jake Tapper

Again and again. Over and over. If Burton got a dollar for every time Wallace objected, before the day was done he could’ve

afforded one of those fancy suits that Warren Christopher and Ted Olson favor. Though the bespoke pinstripe isn’t quite South

Florida style.

Fort Lauderdale attorney Ben Kuehne, Wallace’s Democratic counterpart, also chimes in. He clearly wants the board to use the

most liberal interpretation of the sunlight rule as they can. Kuehne’s backed by three of Whouley’s Boston Boys, Dennis Newman,

Jack Corrigan, and David Sullivan. “Turn the card over,” Kuehne says at one point—since light can sometimes be seen if the

ballot is held at a different angle.

Wallace gets mad. The board, made up of three Democrats, is listening to Kuehne more than to him, he says.

Roberts insists that she was already holding the card at different angles, that Kuehne’s advice was redundant.

“You’re injecting a partisan flavor to the process,” Wallace says. “It’s not right.”

At around 3:45, a ballot is held up that has light shining through the no. 3 chad—a Bush vote.

“There is light through there,” Wallace says.

“I see light,” Roberts agrees.

“Thank you, Carol,” Wallace responds.

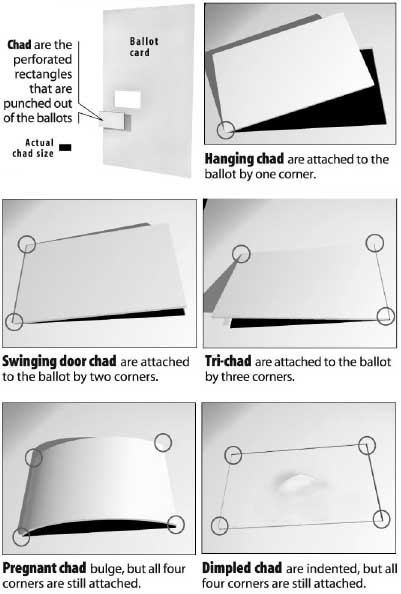

Roberts shows Burton a dimpled chad, sans light.“Somebody attempted to push something,” she says.

“Even though you see someone attempted to do something, you see no light,” he says.

Wallace tells them to be careful handling the ballots. Bending them could cause chad to improperly fall from the ballot, he

cautions.

Burton sighs heavily.

“Yes on a number three right here,” Burton says, pointing to a Bush vote.

“Woohoo!” Wallace cheers.

The canvassing board realizes that it’s now being more lenient with the sunlight standard than it was at the beginning of

the precinct’s count. The board agrees to look at some of the earlier ballots with the newer, more lenient standard.

“That is completely not fair,” Wallace says. “It’s another recount.”

“It’s a changing standard, I suppose,” Burton allows.

“Light is light,” Wallace says.

“We’re here to make sure everyone gets a fair chance,” Roberts says.

But to Wallace, even if the board applies the same new standard—what he refers to when he objects that “the sunshine rule

doesn’t apply to a micron of light!”—it’s pretty clear what’s going on. Palm Beach County went for Gore over Bush 67 percent

to 33 percent. Even if the pinhole votes are fairly distributed, that’s still a 2-to-1 Gore advantage.

His objections reach a fever pitch. Sometimes. Burton shows him a ballot that appears to be unpunched. “The only argument

would be right here,” he says to Wallace, pointing to the Bush no. 3 slot. “That’s no argument, that’s light,” a suddenly

agreeable Wallace says.

Funny how that works.

At 4:25

P.M

., Burton lets out an enormous bearlike yawn.

“We all feel the same way,” an elections worker jokes.

In Austin, Bush spokeswoman Mindy Tucker is watching the count on TV.

“How ridiculous,” she thinks. “I can’t sit here and watch this. This is the most ridiculous thing! Everyone keeps saying:

no one wants to see sausage made. This is proof of that.”

And that’s the trick, she realizes.“If America sees this, everything we said about hand counts is being illustrated on national

TV,” she thinks. “This is playing right into our hands.”

You know this meeting at the vice president’s residence at the Naval Observatory, or “NavObs,” is important, because Joe Lieberman’s

being asked to attend it on the Shabbos. His chief aide, Tom Nides, is sent to fetch him at a friend’s house, where he’s eating

lunch after attending synagogue. During the campaign, Lieberman had said he would work on the Sabbath only if it were a matter

of national importance, never if it was just a matter of politics. Clearly, Lieberman has no question in his mind as to which

category this meeting falls into.

When Lieberman and Nides arrive, the meeting begins in Gore’s dining room. Gore’s there with Tipper, Daley, Christopher, Bob

Shrum, Carter Eskew, with Klain and some of the Florida lawyers on the phone from Tallahassee, Fabiani from Nashville.

Daley’s happy. The Bushies didn’t file any recount requests within the seventy-two-hour period. It’s a victory! Their attitude

is clearly, “We ain’t playing, period,” but maybe that will be a mistake by them.

Gore suggests that he go on TV that night to give a simple message. Even though lots of people have clearly been disenfranchised

by some irregularities at the polls, he will willingly back off any challenges about them—butterfly ballots, African-Americans

kept from voting this way or the other—if Bush goes along with a statewide hand recount. It can be over in a matter of days,

and it will be winner take all, and the matter will be settled.

Fabiani thinks that it’s a good idea, but he wants to hold off on it until Sunday late afternoon. This is maybe the ultimate

speech of your political career, Fabiani says. Doing it Saturday night, when few people are watching, and when it’s too late

to get into the Sunday newspapers, doesn’t make sense. The speech still has to be written, there’s no forum in which to give

the speech yet, for such a major speech let’s do it right. Let’s do it after the football games Sunday afternoon.

Gore agrees.

But Klain, Lieberman, and others begin talking him out of the idea. You can’t do this, they say. It’s so early in the process;

we don’t know what would happen in a butterfly ballot lawsuit. We don’t know if something terribly egregious happened on Tuesday

with black voters that we have yet to hear about. You can’t give these things up without knowing what the details are.

“I’ve been a lawyer, I was attorney general of Connecticut,” Lieberman says. “One thing you learn when you’re in those positions

is you don’t take anything off the table until you know all the facts. And we don’t know all the facts.”

Daley’s a big basher of the butterfly ballot suit. It sucks, sure, but there’s no remedy. “People get screwed every day,”

he says. He and Christopher are in favor of the four-county hand recounts.

But as the hours pass, Gore’s idea to call for a statewide recount will be pretty much scrapped. Fabiani will spend the rest

of his life kicking himself for not letting Gore give the speech, for not arguing more vociferously against the lawyers’ demand

that nothing be ruled out.

Kerey Carpenter, thirty-nine, an attractive strawberry-blond, is a litigator and assistant general counsel for Secretary of

State Katherine Harris. On Friday, she was sent to Palm Beach because of all the butterfly ballot litigation that names Harris

as a co-defendant along with LePore. Before she left, Carpenter was given a silver “Division of Elections” badge by division

of elections director Clay Roberts, one she clips inside her wallet. She flashes it around, gets in everywhere she wants.

Kuehne wonders just who the hell she is. Initially he thinks she’s the county attorney, Denise Dytrych, since Carpenter walked

out with the canvassing board from the elections office into the counting room. And Carpenter almost immediately arouses Kuehne’s

suspicions when she offers advice about something innocuous, with an air of precision, that Kuehne doesn’t think is right.

Kuehne asks the Boston boys just who she is. They don’t know. Newman, too, has been wondering who the “mystery woman” is.

She’s obviously important, because she has access to everyone.

Kuehne sidles up to Leon St. John, an assistant county attorney.

“Who is that?” he asks.

“She’s one of the elections lawyers,” St. John says.

“Oh, she’s with the county?” Kuehne asks.

“No, she’s with the state,” St. John replies.

It hits Kuehne: this woman is with Harris’s office.

From then on he views every word from her mouth from this perspective: Carpenter is from the Jeb Bush administration sent

to help Jeb’s big brother. She’s a political hack who has little knowledge of election law, he thinks. She’s giving political

advice, not legal advice, he thinks. He’s shocked to see the preeminent role she plays. She goes back with the canvassing

board members when they go to their offices during breaks, as if she’s the canvassing board’s outside counsel. This, Kuehne

realizes, is not good.

At about 5:00

P.M

., the board decides to break. Roberts needs her MOREs, and Burton needs his Marlboro Lights.

In the small outdoor dining area adjacent to the Governmental Center, Wallace approaches Burton and implores him to stop adhering

to the more lenient standard. He thinks the Democrats are stealing the election by finding votes where no votes are to be

found. It’s inappropriate, he thinks. He hadn’t had a problem when they started with the sunshine rule, because he’d assumed

it was going to be applied as it had been applied in the past in other counties. But it was ridiculous now, the things they

were calling votes.

I don’t think you can do this, Wallace says to Burton. You’re a judge, you’re a reasonable man. “Please,” he says to Burton.

“Think about it. Your actions are going to be judged for a long time.”

Burton doesn’t say anything. Wallace walks away.

Carpenter also approaches Burton, taking a drag on one of her Benson & Hedges DeLuxe Ultra Lights and talks to Burton about

her office’s position on when a full hand recount is allowable under the statute. It’s supposed to be only when there’s machine

error, she says. Not voter error, which is how her office regards undervotes.

During this break, Burton tracks down county attorney Leon St. John. “I’m a little uncomfortable about this,” he tells St.

John, about the standards they were using before the break. Some of the chad they were counting as votes weren’t even dimpled,

they merely had a little pinprick of visible light. Burton thinks it’s absurd, ridiculous. He doesn’t think they’re following

the 1990 standard. “Bring it up,” St. John says.

In the counting room, no one knows where Burton is. Time passes. Soon enough, he returns with something to share: the 1990

standard.

“The instructions in the voting machine are as follows: