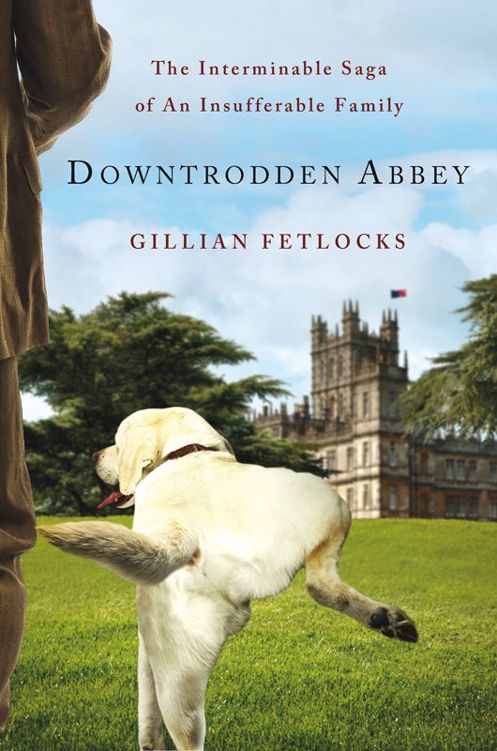

Downtrodden Abbey: The Interminable Saga of an Insufferable Family

Read Downtrodden Abbey: The Interminable Saga of an Insufferable Family Online

Authors: Gillian Fetlocks

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

FOR LADY FREDERICA HOBIN

CONTENTS

V.

Where Has All the Flour Gone?

VIII.

Hair Apparent

IX.

About Smutt

XII.

Good Lord!

XIII.

Renewal (?)

PART THREE: BEING THE THIRD OF THREE PARTS

XV.

Irish Stupor

“We have all read books that should never have been published.…”

FOREWORD

It may be useful to begin with the great house itself.

The construction of Downtrodden Abbey was commissioned in 1659. The reputation of the architect, Inigo Schwartz, is still a subject of considerable debate. Depending on whom one believes, he was known for either unlimited patience or incessant dilly-dallying. For example, a small village originally occupied the land on which he planned to build. But as a courtesy—and in accordance with the etiquette of the day—Inigo Schwartz waited for every one of the residents to contract smallpox and expire before actually breaking ground. Would that such manners pervaded all of England’s citizens in the Edwardian Age!

After waiting for the drafting table to be invented, the master designer generated plans for what was to be his crowning achievement: a dwelling massive enough to contain the secrets of the Earl of Grandsun and his descendants. In other words, the Earl of Grandsun’s sons, daughters, grandsons, and granddaughters. And the Earl of Grandsun’s grandsons’ sons and grandsons, and so forth.

Schwartz hired labourers to dig the foundation. Claiming a carriage failure on the way, they arrived two hours late, and immediately broke for lunch. However, as this was a fourteen-year project, they were forgiven. Masons eventually began to lay the stone; one enterprising and quite fortunate worker managed to do the same to Schwartz’s fetching wife.

Fittingly, architect Inigo

Schwartz’ wife was built.

Finally, the structure was completed. In 1675, the first Earl of Grandsun moved into Downtrodden Abbey with his wife, who immediately took to bed, despondent over the colour of the drapes. Months later—as was common in that troubled era—this was reported as the official cause of her untimely death.

Electrical power came to the abbey in stages. Originally the first floor was electrified, then the bedrooms were electrified, and then the servants’ quarters were electrified. (Lady Marry Crawfish, a later earl’s eldest daughter, was electrified by the appearance of an Arab in her boudoir—but more on that later.)

As group clamouring was a popular activity of the day (according to Simon Potter’s seminal study,

What’s the Big Deal? Edwardian Group Clamouring and Its Consequences

, Dinder-Mufflin, 1931), visitors from all around the world clamoured to see the great house. These annoying gawkers would make drawings, take daguerrotype photographs, dance the popular “Downtrodden Jig” on the grounds of the estate, and colourfully describe the property in missives they sent back home.

“Yah, it is a most impressyve hoöse, one vich does not appear to have been put together from a kit,” said the Swedish builder Allen Wrench.

“I wish my wife were built like this,” wrote a comedian, who travelled to the abbey from Russia’s Borscht Belt, ostensibly just to break out that old chestnut.

The “Downtrodden Jig” was a fad for the ages – if not the aged.

“What am I doing here?” asked the German neuropathologist Alois Alzheimer during his 1906 trip to Downtrodden.

“The abbey is both pleasing to the eye and functional,” said an architectural writer of the day, who was known to occasionally lapse into overzealous hyperbole. “It is a towering tribute to the wonders of modern industry, a marvel of design, and a triumph of the human spirit. Were it possible to engage in illicit acts of a carnal nature with a building, one would undoubtedly find Downtrodden Abbey a most suitable partner.”

I. M. Hyly-Pade

Big-Time Architect

PREFACE

Let us now concern ourselves with some historical context for the story of this extraordinary house and its occupants.

Many do not realize that King Edward VII’s reign was a scant nine years, beginning in 1901. Britain was a most ill-regarded country, in large part because the Boer War was still raging. Etymologists from every district waged battle in pubs over the correct spelling of the word “Boer,” the early versions of which were “Bore” and “Boar.” Fights broke out; many combatants died (ironically, of boredom). Others flourished in academia, where heavy alcohol consumption and protracted debate over utter nonsense has since been both encouraged and rewarded.

While the spelling over their name was being argued, the Boers kicked some serious limey posterior, as the British Army were cursed with overly thick uniforms, faulty sweat glands, and a collective lacklustre attitude. Rather than providing relief, occasional rain made the Conflict even more challenging for the British side, as the soldiers insisted on fighting whilst holding umbrellas.

In 1902, the Boer War ended. King Edward elected to test his questionable reputation with a cruise to Paris, and was disappointed to discover that he could not get a good table in a single decent restaurant. Nonetheless, upon his return to Blighty, the king delivered a series of speeches extolling the virtues of Paris, in an effort to restore good will between the nations. Aside from mistakenly referring to France’s capital as “The Windy City,” these upbeat talks did ultimately serve to bolster relations, particularly between the king and his French maid, Monique, who was aroused by any positive mention of her homeland.