Drama (13 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

S

o in this whirlwind of grinding academics and amateur theatrics, when did I decide to embrace my destiny and become a professional actor? I can narrow it down to a minute-long span of time late one evening in December of 1964.

It happened like this.

From that long list of student productions from my four years at Harvard I’ve left one title out. It is

Utopia, Limited; or, The Flowers of Progress

, an 1893 operetta by Gilbert and Sullivan. An epic-sized and overdrawn satire of British colonialism on a South Sea island,

Utopia, Limited

is the least known and least performed of the entire G&S canon. It is a raucous, vaguely racist piece of work that probably deserves its obscurity, but in my own modest history it looms large. Although an unlikely candidate for a life-altering experience,

Utopia, Limited

was the show that distinctly altered my life.

Early in the autumn of my sophomore year, a production of the operetta was slated for the Main Stage of the Loeb Drama Center. Its director was an intense and brilliant young man named Timothy S. Mayer. As seductive as he was abrasive, Tim Mayer was one of the most extraordinary characters I’ve ever known, and he looked the part. He was stoop-shouldered and pocky, with a rope of dark brown hair always hanging in front of his piercing, bespectacled gray eyes. He sported expensive tweeds and penny loafers, but the clothes hung shabbily on him and he wore no socks. He spoke in a language all his own, rapid-fire and dazzlingly clever. A heavy drinker and nonstop smoker, he was a man whose prodigious talent was matched by an equally prodigious strain of self-destructiveness. During his Harvard career, he would churn out a long string of electrifying productions, but he never scaled the same heights in the hazardous world of professional theater. As if consumed by his own demons, he died tragically young, of cancer, in his early thirties. By a quirk of fate, this amazing young man was to have a catalytic effect on the next several years of my life.

Of the many shows Tim directed at Harvard,

Utopia, Limited

was his maiden effort. He was fiercely determined to make a splash with it and to disprove the old adage that Gilbert and Sullivan is more fun to perform than to actually watch. His take on it was startlingly original. In W. S. Gilbert’s creaky, campy Victorian humor, he saw hidden strains of bitter, almost savage anti-imperialism. For all its high spirits, this was to be the thrust of his production. He pitched it on a grand scale, with an enormous cast, a thirty-piece orchestra, and lavish, pastel-colored costumes and sets. But as Tim conceived it, all of this extravagance was shot through with acid irony. He had joined forces with Gilbert to skewer Victorian smugness and arrogance, seventy years after the fact. With the bravura that would soon earn him the nickname “The Barnum of Brattle Street,” Tim touted

Utopia, Limited

(accurately) as the biggest spectacle yet produced at the Loeb.

All fall the Loeb was abuzz with breathless rumors of this magnum opus. But perilously late in the rehearsal period, the production was dealt a crippling blow. The actor playing the central comic role of King Paramount, ruler of the island nation of Ulalica, abruptly walked off the show. Suddenly this colossal enterprise had no leading man, and Tim Mayer, a frazzled director at the best of times, was desperate for a replacement. By now, my performances in Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Shaw had accorded me an embryonic star status in the tiny world of Harvard theater. So Tim sought me out. The phone rang in my dorm room. I answered. Mincing no words, he got right to the point:

“Can you sing?”

I’d never sung onstage in my life, and I told him so. But I knew plenty of songs. And so a half hour later I was standing on the stage of the Loeb, belting out an a cappella version of an English music hall song titled “I Live in Trafalgar Square.” I sung the last note and stared out into the house. With a shout, Tim cast me on the spot, and that evening I walked into my first rehearsal, leaping onto the speeding train known as

Utopia, Limited

.

In the run-up to our first performance, I was rushed through a kind of musical-theater boot camp. I was spoon-fed my recitatives and arias; I was drilled on the bass line of all the four-part singing; I was even sent downtown to the New England Conservatory for a few last-minute voice lessons. Ideally, the role of King Paramount should be sung in a big, resounding bass. For all my efforts, I never got beyond a thin, reedy baritone (and over the years, I haven’t improved much on

that

). But my pitch was reliable, every word was crystal clear, and I strove to squeeze every drop of wit out of Gilbert’s lyrics. And in all the book scenes, on much firmer ground, I was effortlessly funny. As rehearsals sped by in the countdown to our opening night, I methodically proceeded, scene by scene, to steal the show.

Act II of

Utopia, Limited

begins with a comic septet, taking its title from the first line, “Society Has Now Forsaken All Its Wicked Courses.” This number is sung by all of the principal men in the cast. As the plot unfolds, the island nation is transformed into an absurd Polynesian parody of English society. The song’s verses, sung by King Paramount, provide a long list of examples of that transformation. The verses are broken up by a snappy refrain sung at top speed by all seven men:

It really is surprising what a thorough Anglicizing

We have brought about—Utopia’s quite another land;

In our enterprising movements, we are England with improvements

Which we dutifully offer to our Mother-land!

The format of the septet is that of an English music hall minstrel show, with the seven men in white tie and tails seated on seven chairs, King Paramount in the middle. Every time the refrain is repeated, the men leap to their feet, producing all manner of instruments. As the song builds, so does the loopy energy of the singers. The lyrics are funny enough, but the theatrics of the staging make the number over-the-top hilarious. By tradition, it is such a hit that the seven singers plan a couple of encores just in case they’re needed, ready to perform ever more elaborate variations on that manic refrain.

Our production was no exception. All eight times we performed the song, we stopped the show with it. But for me, the first time was the life changer. That night, when the song proper came to an end, the applause was deafening. We all remained onstage, poised for our first encore. The conductor powered up the orchestra again, silencing the crowd. I repeated the last verse, and the seven of us bellowed the refrain. This time I did a frenzied mock tap dance with one of the men rapping on the stage floor at my feet with a pair of drumsticks. This brought an even bigger response from the crowd. Once again we stayed onstage, and once again we performed an encore. For this one I produced three Spaldeens, spray-painted gold, and juggled them inanely all through the refrain. An even

bigger

response. By now the crowd was delirious. We had only plotted the two encores, so the other six men picked up their instruments and chairs and walked into the wings. I remained onstage alone, ready to begin the next scene.

But the audience did not stop applauding.

The applause swelled into cheers. The cheers became a roar. I suppose the ovation must have lasted about twenty seconds, but to me it seemed five minutes at the very least. I stood there, grinning like an idiot, dizzy with the overdose of adulation pouring down on me.

That twenty seconds was all it took. There was no longer any question. I was going to be an actor.

MS Thr 546 (147), Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Hard Times on the Great Road

I

n 1966, the ground began to shake under our feet. The Vietnam War had grown into a major conflagration. Every Harvard student was grappling with the queasy reality of the draft. SDS antiwar rallies on Mt. Auburn Street were drawing larger and larger crowds. American rock and roll had risen to the challenge thrown down by the Beatles and the Stones. Bob Dylan had gone electric. Late-night dorm-room dope-smoking sessions had been a dark, paranoid ritual; now they were an offhand folkway. Students from California were returning from breaks with lubricious tales of LSD trips and orgies. The confluence of feminism and the Pill was transforming sexual mores and reducing Harvard’s rigid “parietal rules,” which barred women from men’s dormitories, to a travesty. Suddenly half the male student population were sporting long hair and scuzzy beards, and finding ingenious ways to mock the school’s fusty dress code. The social and political cataclysm of 1968 was still a couple of years away, but an atmosphere of liberation, radicalism, and incipient rebellion already hung in the air.

But the rushing waters of social change were flowing right past me. In September of 1966, before the start of my senior year at Harvard and a month shy of my twenty-first birthday, I got married.

I married Jean Taynton, the daughter of the librarian of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Jean was six years older than I and had been living and working in Cambridge, just blocks away from the Harvard campus. In those days she taught special education to public school kids with a wide range of emotional problems. We had met a year before, working together at the Highfield Theater, a summer light-opera company in Falmouth, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod. The theater was a summer adjunct of Oberlin College and its Music Conservatory, out in Ohio. Years before, as a student at Oberlin, Jean had spent several summers at Highfield, performing a long list of comic character roles. As a lark, she had returned there to appear in

Patience

, yet another Gilbert and Sullivan warhorse. She had come at the behest of the show’s young director, a rich, precocious Harvard boy from nearby Cotuit who had been hanging around the Highfield summer playhouse for years. Those summers had been the source of the boy’s early infatuation with musical theater. By sheer persistence he had landed a directing job there at the age of twenty. The boy’s name was Timothy S. Mayer.

After our happy collaboration on

Utopia, Limited

the year before, Tim had little trouble persuading me to join him at Highfield. The season was to feature eight operettas, four of them directed by Tim himself.

Patience

was to be the first. This florid comic romance was W. S. Gilbert’s cheerful satiric swipe at Oscar Wilde and nineteenth-century aestheticism. Tim cast me as Bunthorne, Gilbert’s patter-song stand-in for Wilde himself. Opposite me, he cast Jean Taynton as Lady Jane. Tim Mayer had thus unwittingly cast

himself

in the extremely unlikely role of Cupid.

From the beginning Jean and I were an odd couple. If I was a six-foot-four string bean, she was a five-foot-two brussels sprout. In

Patience

, our physical incongruity made us a hilarious pairing, a kind of Edwardian vaudeville team whose scenes were the comedic high points of the show. With Jean’s herky-jerky dance moves and a deep contralto singing voice emanating from her compact little body, she outdid even W. S. Gilbert in mocking the conventions of Romantic light opera. For my part, the

Utopia, Limited

experience had liberated the zany song-and-dance man in me. As Bunthorne, a foolish popinjay in a floppy beret and purple faux-velvet, I hurled myself into my role with campy, loose-limbed enthusiasm. Every night for a week I leapt around the stage in that stuffy, sweltering little playhouse, soaked with sweat. Months later I learned that at the end of the show’s run (as with every other show that summer), the wardrobe crew had held a ritual burning of my fetid costume.

Patience

was such a ball that Jean offered to stay on at Highfield for the summer and play several more roles. Stirred by the exuberant fun of our onstage hijinks and by a long list of overlapping enthusiasms, we became inseparable pals and, within weeks, curiously mismatched lovers. To my youthful eyes, Jean was a blend of effervescence and gravitas, of girlishness and maturity. This duality showed in everything she did. Her bubbly nature concealed a strain of caustic wit. She was a serious, compassionate teacher who spearheaded weekend games of coed touch football. She had an abiding passion for classical music and the Old Masters, yet her great hero was Bill Russell of the Boston Celtics. Her piping voice verged on baby talk, and yet she held forth with penetrating intelligence on poetry, fiction, philosophy, and psychology. I was nineteen years old when we met. At that age, a six-year age difference is enormous. Yet Jean presented a wide-eyed, Peter Pan version of grown-up life that, for mysterious reasons, seemed to be just what I was looking for. When the Highfield season ended, she returned to Cambridge to her teaching job, I returned there for my junior year of studies, and she became my off-campus girlfriend. After two years at Harvard, my social life had barely gotten under way. Now it was pretty much over with. As for the great youth revolution known as “The Sixties,” it had started without me.

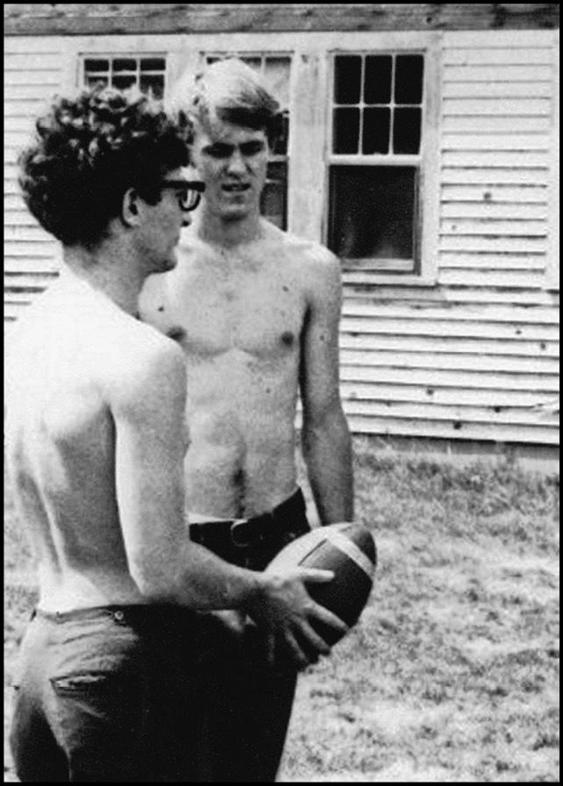

A good friend named Tim Jerome was also an actor at Highfield that summer. Recently he came across a candid photo from back then and sent it to me. The photo showed him and me forty-five years younger. We are shirtless and winded, having been tossing a football. I am pale, rawboned, and painfully thin. My hair is long and Byronic. Seeing the photo in the present day was a shock. I barely recognized myself. In my memories, I was a strapping, confident young man that summer, with the world on a string—nothing like the callow schoolboy who stared out at me from that photo. My heart sank at the sight, and a harsh question formed itself in my mind:

“Who in the world does that kid think he

is

?!”

I was a deeply confused young man and I didn’t even know it. Having successfully navigated a childhood of constant, disruptive change, and having turned myself into a roaring furnace of compensatory creative output, I had ended up with delusions of adulthood. Everywhere I went I was a whirling dervish of artistic enterprise, hailed as a kind of Midas-like talent. But the pride and pleasure I derived from all of my projects masked a troubling truth: I was sublimating like crazy. I had conveniently ignored an essential stage of my emotional development. I had dispensed with adolescence. In my mind, I was socially and artistically complete—a fully functioning adult and the second coming of Orson Welles. On both scores, I was woefully mistaken. And that misperception of myself was to be the root cause of a world of troubles in the decade to come.

For starters, there was “The Great Road Players.”

The Great Road Players does not rate a footnote in anyone else’s history, but it is a significant chapter in mine. Halfway through my college career, subconsciously reenacting my father’s youthful exploits, I hatched a plan for my own summer theater. My growing list of stage successes at Harvard, both as an actor and as a director, had boosted my confidence, inflated my ego, and spurred me on to this next step. When the idea was still barely embryonic, I happened upon an eager confederate. A sharp young New York actor named Paul Zimet showed up in Cambridge one day in late autumn of 1965. He was visiting a woman friend of his, a dancer who was appearing in one of my Loeb productions. I met Paul at an off-campus party after he had seen the show. A gentle soul with the dark good looks of Montgomery Clift, I liked him immediately. The fact that he had loved my show inclined me to like him even more. In the intense conversation that followed, I aired my ideas to him for a theater workshop the following summer. That very night we decided to team up, plotting the workshop together. I don’t recall having the slightest doubts about our partnership or feeling for a moment that I was acting with precipitous haste.

That night of crazed optimism was the starting point of a journey that, several months later, would end in irredeemable disaster. With zero experience as an actor-manager and with a producing partner I barely knew, I proceeded to make just about every bad decision I could have possibly made. To begin with, I picked the wrong setting. Instead of Cambridge, the scene of all my recent triumphs, I set my sights on my hometown of Princeton, New Jersey. And as a mentor and shadow executive producer, I chose my father.

By this time, Dad was in his third year as artistic director of the McCarter Theatre. I looked to him for advice, for logistical support, and for protective cover. Distracted by the continuing pressures of his own job, he listened to my grand scheme with an aloof, abstracted air. If he had any doubts, he didn’t show them. He signed on to the idea and breezily guided me through the basics of institution building. He helped me enlist a board of directors, composed mostly of Princeton boosters with their roots in community theater. He put his McCarter staff at my disposal to help me with such matters as press releases and brochures. And he accompanied Paul and me as we checked out possible performance spaces around the town. Through it all, he maintained a kind of bemused indulgence, with nary a whiff of skepticism or devil’s advocacy. His own history was checkered with cautionary tales of ill-advised theatrical ventures, some of them downright catastrophic. But he shared none of those tales with me.

We found a beautiful theater. It was the brand-new, barely used auditorium of The Princeton Day School, a tony private school ten minutes outside of town. The school’s administrators were proud as pink of their new facility, flattered by our interest, and tickled by the notion of presenting plays to the public on their remote campus. With a heedless naïveté that I am sure they have never displayed since, they put the space at our disposal as summer tenants. On our first trip out to the school, we passed a signpost en route. The signpost bore the name of the country lane where the school was located. It was called “The Great Road.” As we drove back into town a few hours later, flushed with success, we had both a home for our new company and a name. We dubbed it The Great Road Players.

A recent graduate of Columbia, Paul was one of a vital group of recent Columbia alumni whose adventures in college theater had closely paralleled my own. Outside of the protective cocoon of academia, he had barely dipped his toe in professional New York theater. He and his Columbia pals had attached themselves to various avant garde troupes in downtown Manhattan. They had also joined a class in Shakespeare performance led by a charismatic English émigré whom I’ll call Tony Boyd. Paul and I intended to form our company by recruiting an equal number of fellow actors from the Harvard and Columbia theater communities. So I traveled down to New York one weekend to confer with him and meet all of his Columbia friends. During the visit, I even visited Mr. Boyd’s Shakespeare class and watched them all at work. As actors they were a completely different species from me and my Harvard gang—impulsive, improvisational, and barely disciplined. But their talent was obvious, I liked them all, and I persuaded myself that our differences would lead to exciting work onstage.

Paul and I picked a slate of four plays derived from work that both of us had already done. Our plan was to follow the model of my dad’s old Shakespeare festivals—to open one production at a time, then to perform them all in rotating repertory, offering subscription tickets to the public. The titles were an arty, eclectic mix, and extremely challenging for a young company. Ominously, they were even more challenging for a pool of Princeton theatergoers looking for light summer fare. Paul was to kick things off by directing

Woyzeck

(the Büchner play that I myself would direct the following year at Harvard). As a curtain-raiser to that gruesome tale, we would also stage an absurdist take on T. S. Eliot’s dialogue poem “Sweeney Agonistes.” I would follow with an evening of Molière one-act farces (including

The Forced Marriage

, which I’d already done twice). The third offering was perhaps our only safe choice (though hardly a piece of cake), Shakespeare’s

Twelfth Night

. I honestly cannot remember what the fourth show was intended to be. It doesn’t really matter. We never got that far.