Dreadfully Ever After (21 page)

Read Dreadfully Ever After Online

Authors: Steve Hockensmith

Tags: #Humor, #Fantasy, #Romance, #Paranormal, #Historical, #Horror, #Adult, #Thriller, #Zombie, #Apocalyptic

“You can’t do this!” another man shouted, and others joined in with, “For God’s sake!” “It’s an outrage!” and the like.

“This is the last time I’m saying it!” the sergeant bellowed back. “New orders. No one gets out without work papers. But don’t get your pantaloons in a bunch! Once the recoronation’s over, everything’ll get back to normal.”

“With one difference,” Coogan said over the squawks of “his” wee one. “We’ll all be dead!”

“And who liked ‘normal,’ anyway?” a woman threw in.

“Yeah!” half a dozen others called out.

A dark-skinned man wearing a red turban and an immense black beard turned and glared at Mary just as she cleared the edge of the crowd. It wasn’t often one saw foreigners in England anymore, for who would come willingly to the Land of the Dead? The fact that most proved immune to the strange plague only made them more resented in a country that was never particularly fond of outsiders to begin with. What remained of the old immigrant populations was rarely seen outside deepest London.

“And how about her?” the man asked in a heavily accented singsong, and he stabbed a finger at Mary. “Will you be asking the lady and her pets for papers when they want to leave? I think not! They’ll be free to come and go while the likes of us stay trapped in here like rats.”

The soldier who’d been doing all the talking waded into the mob and drove the butt of his Brown Bess into the outlander’s stomach.

“Keep a civil tongue and don’t forget your place.” The sergeant turned toward Mary as the bearded man doubled up in pain beside him. “I do apologize for that, Miss. All sorts of unpleasantness you’re bound to encounter here today. Even more so than the usual, I mean. You won’t be staying long, will you?”

“Just long enough,” Mary called back, and she and Mr. Quayle and the dogs carried on up the street.

The unpleasantness they’d been promised presented itself quickly enough: More bodies had been left out for collection, the heaps reaching as high as Mary’s chest in spots, and here and there soldiers worked in teams of two, collecting the heads of the dead and the dead-ish with heavy sabers. Even where the corpses were starting to get frisky, the soldiers never fired a shot. Instead, one would pin the stricken in place with a bayonet or pike while his partner finished the job with his sword. The practice conserved powder and musket balls, of course, but Mary suspected that wasn’t the only reason for it.

The walls would spare respectable London the sight of an epidemic, but even stones and mortar twenty-five feet high couldn’t blot out the sound of so much gunfire.

“We were lucky to get in ... depending upon one’s definition of ‘lucky,’ ” Mr. Quayle said. “Tomorrow, without doubt, the quarantine will be total. No one in or out.”

“Agreed. Which makes it all the more imperative that we act immediately.”

“Agreed.”

They turned a corner and found themselves moving up a street that had yet to see its morning visit from the soldiers and body wagons. The locals had done what they could with their Zed rods, and the cobblestones were coated with fresh-pulped brains and bits of shattered bone. Still, there were stirrings in several of the corpse heaps, and Ell and Arr slowed and bared their teeth and growled.

“This is intolerable,” Mary said. “How could they allow it to become this bad?”

“Of which ‘they’ do you speak?”

“The authorities, of course. The government.”

Mr. Quayle’s box let out a little squeak.

“That was a shrug, Miss Bennet,” Mr. Quayle said. “Of the cynical, world-weary variety. Section Twelve Central and all such sections like it will always be tolerated, no matter how appalling they become, because it is easy to tolerate that which one ignores. And, at the moment, the authorities—and those who keep them in power—have all the more reason to focus their attentions elsewhere. There is a king to be recrowned. There are balls and banquets and jubilees to plan. The only thing that would be intolerable would be spoiling the fun.”

Mary looked down at the box rolling along the blood-slimed street and wondered, not for the first time, what the man inside it looked like.

“You have a didactic streak, Mr. Quayle,” she said.

“My apologies.”

“You misunderstand me,” Mary said, and for perhaps the first time in her adult life, she gave in to an impulse: She rested a hand atop Mr. Quayle’s box, the fingers spread wide. “I meant that as a compliment.”

“Ah. It has been so long since I received one, I failed to recognize it for what it was.”

Mr. Quayle’s voice was even gruffer than usual, and for a long while the only sound that came from his box was the rumbling of the wheels over the cobblestones.

Eventually, they reached the abandoned brewery Mr. Quayle preferred when keeping watch on Bedlam.

“It offers more seclusion than the alleyway you used for your observations yesterday,” he explained as they made their way past cobweb-covered casks and vast copper vats streaked with grungy green. “A kidsman and his gang of thieves have claimed the place as their den, but they shan’t disturb us. We came to an understanding long ago, they and I.”

“That understanding being …?”

“That if I am left to my business, they are left to theirs, including the business of breathing.”

“A happy arrangement for all.”

“Quite.”

“One thing puzzles me, however.”

They stopped in front of a staircase leading up to a walkway lined with shattered windows. Long wooden boards had been placed end to end from the bottom of the stairs to the top, creating a convenient gangplank for Mr. Quayle. Above, more boards led to a crate placed by a window that, Mary assumed, afforded the best view of the hospital grounds.

“Nezu told us that Lady Catherine’s ninjas have attempted to infiltrate Bethlem in the past,” Mary said. “And here I find that you have a cozy observation post that has seen no little use. Yet Mr. Darcy was tainted with the strange plague only two weeks ago.”

“You wonder why Her Ladyship would take such an interest in Sir Angus MacFarquhar

before

her nephew was infected.”

“I do, indeed.”

“I have wondered the same thing. My mistress has not seen fit to tell me, however. Nor have I felt quite suicidal enough to ask.”

Ell and Arr joined the conversation now, growling in harmony as they raised their wet black noses and snuffled at the brewery’s musty air. Mary copied them (minus the growling), tilting back her head and sucking in a long, deep breath through flaring nostrils, as Master Liu had once taught her. (“You cannot taste what is on the wind with a dainty sniff. You must fill your throat, your lungs, your whole being! Now try again—with these crickets up your nose this time.”) The fetid stench of rotting wood and yeast and barley lay like a waterlogged blanket over every other scent, however, and Mary could smell nothing else.

After a moment, she began to

hear

. It started as a rustling sound and then became a scraping and pawing, all of it strangely echoey and metallic.

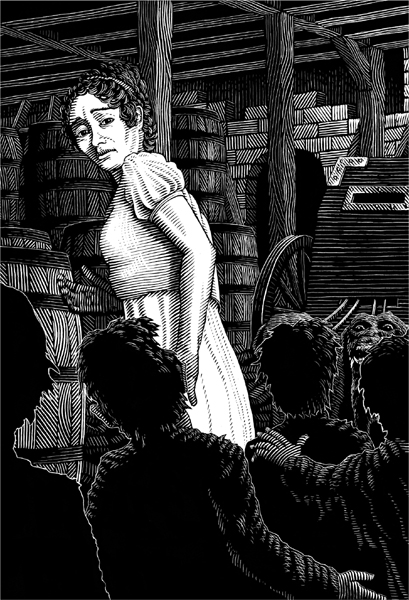

Mary looked at the top of the farthest beer vat just as a pair of hands appeared there. Rising between them came the scowling face of a sunken-eyed child. The boy hauled himself over the side and dropped to the floor, and within seconds more came spilling out after him, as though the vat were a cauldron boiling over with angry, rag-wrapped children.

Ell and Arr wheeled around to face them, snarling and snapping.

“Solomon! Solomon, where are you?” Mr. Quayle shouted. “Come out and call off your dogs, and I shall call off mine!”

“I think your understanding with Mr. Solomon is no longer in effect,” Mary said, “for his wards are now beyond any understanding at all.”

Another boy came crashing to the floorboards with what looked like a large reticule in one hand. It was, in fact, a man’s head, clutched by the long grey beard that grew from the pain-contorted face. The eyes were rolled back in their sockets to point at a smashed crown dripping blood and morsels of brain.

“Mr. Solomon?” Mary asked.

“Mr. Solomon,” Mr. Quayle replied.

The cholera had swept through the thieves’ crib, it seemed, and now Mr. Solomon’s gang was interested less in picking pockets than in emptying skulls.

The boys were already loping forward toward the intruders/buffet.

“MR.

SOLOMON’S

GANG

WAS

LESS

INTERESTED

IN

PICKING

POCKETS

THAN

EMPTYING

SKULLS

.”

“Let’s see if this drives off the little guttersnipes,” Mr. Quayle said, and at a cluck of his tongue Ell and Arr slipped from their harness and stepped aside.

A panel opened near the base of Mr. Quayle’s box, and a long dark tube slid out.

“Very impressive,” Mary said.

She was looking down at the barrel of a pistol.

“I told you Ell and Arr could load a gun,” Mr. Quayle said (before adding a mumbled, “Just don’t ask how I fire it”).

Then he did whatever it was he had to do, and there was a boom and a puff of smoke and a distinct “Ouch!” from inside the box.

One of the zombie-boys pitched backward and lay still.

The rest—half a dozen in all—kept coming.

Mary had already drawn her own pistol, and she brought down another slavering waif just as the diminutive mob reached her. Using the cloud of gunsmoke as cover, she spun to the side and let the dreadfuls hurl themselves fruitlessly into the swirling gray haze. By the time the smoke began to clear, she’d swept the feet out from under two of the unmentionables and had sent the butt of her pistol smashing through their foreheads. Ell and Arr, meanwhile, had brought down another dreadful in tandem and were working with frenzied, frothing fervor to chew through its neck before it could rise again.

Mary whipped around, looking for the last two zombies, and found them hunched over Mr. Quayle’s box, which they’d knocked backward onto the floor. Despite the clumsiness of their clawings, one or the other had managed to trigger some hidden spring, and the front of the black case swung open.

“Uhhh, Miss Bennet. If you might oblige?” Mr. Quayle said.

Mary was already moving. With a warrior’s cry so shrill it seemed to startle even the unmentionables, she hurled herself into a double-handspring, flipping end over end over end over end. She landed directly behind the dreadfuls, unleashed another screech, and then grabbed the tousle-haired heads and slammed them together. Three quick thumps and they cracked like eggs. With the fourth, black goo began to spew this way and that. By the seventh, there was little left for Mary to beat together, and she finally let the bodies drop to the floor.

“Mr. Quayle, are you—?”

“Ell! Shut!”

Ell came bounding over and dipped her furry head under the door to Mr. Quayle’s case. Before the dog flipped it closed, Mary caught the quickest glimpse of a dark-haired man, impeccably dressed despite having no need for trouser legs or sleeves, his face turned to the side and pressed into the plush red velvet that lined the inside of the box.

“You’re obviously a woman with a strong constitution, Miss Bennet,” Mr. Quayle croaked. “Gazing upon me, however, would no doubt sicken even you. Arr! Up!”

Arr stopped chewing on the snapped zombie spine he’d been enjoying and padded over to join Ell. Through a series of complicated though clearly well-practiced steps—one dog nosing slowly under the back panel, the other pulling gently on the reins—they began righting Mr. Quayle’s box. Of course, Mary could have done it for them in seconds, yet, with an instinctive sensitivity that hadn’t before been her forte, she knew to leave them to it.

“I do believe that was the finest example of Satan’s Cymbals I’ve ever seen,” Mr. Quayle said, his wheezy voice turning breezy in a way that suggested a desperate desire to change the subject. “Complete destruction of both crania and all their contents in less than ten blows. Superb, Miss Bennet. Simply superb.”

Mary was grateful Ell and Arr hadn’t finished getting their master off his back. With his view-port pointed at the ceiling, he wouldn’t see her blush.

“You know Satan’s Cymbals?” she said. “So you were trained in the deadly arts, then.”

“Oh, yes. I once fancied myself quite adept ... though the skills came more easily to me than the disciplines, if you follow me.”

Rather than pause to see if she did, Mr. Quayle pressed on quickly.

“And what of your training, Miss Bennet? What masters can claim credit for so skilled a student?”

“I was introduced to the ways of death by my father and a man named Geoffrey Hawksworth. But the bulk of my training was in China, under the Shaolin master Liu.”

“Liu. Yes. Of course. The man is a legend among those who follow the Shaolin path. This Hawksworth, however. What can you tell me of him?”

Mary felt her blush deepen. There was what she

could

tell of Geoffrey Hawksworth, and what she

would

.

“I don’t know much about him, really. Eight years ago, he came to Hertfordshire to train my sisters and me. He only stayed a matter of weeks. That was at the time of the Return, you see, and he ... he seemed to abandon us to the dreadful hordes.”