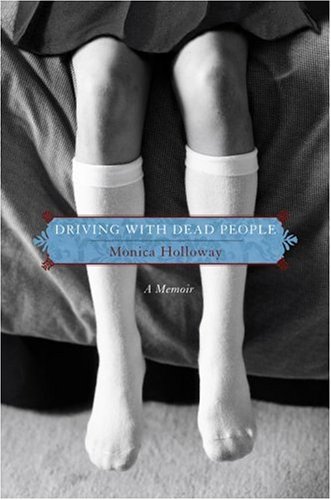

Driving With Dead People

Read Driving With Dead People Online

Authors: Monica Holloway

Brief quotes from table of contents, Chapter 8 and 12 from

The Courage to Heal, Third Edition, Revised and Updated

by Ellen Bass and Laura Davis copyright © 1994 by Ellen Bass and Laura S. Davis Trust

Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers

Excerpt from the poem “Remember, Even the Moon Survives” copyright © 1994 by Barbara Kingsolver

Reprinted by permission of The Frances Goldin Literary Agency

SIMON SPOTLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT

An imprint of Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10020

Copyright © 2007 by Monica Holloway

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. SIMON SPOTLIGHT ENTERTAINMENT and related logo are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Yaffa Jaskoll

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Holloway, Monica.

Driving with dead people / by Monica Holloway.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4169-3610-7

ISBN-10: 1-4169-3610-6

1. Holloway, Monica. 2. Problem families—Biography. 3. Undertakers and undertaking—Family relationships. 4. Interpersonal relations—United States. I. Title.

CT275.H6443A3 2007

977.2’043092—dc22

[B]

2006026316

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

This book presents the story of my journey from childhood to adulthood. All incidents are portrayed to the best of my recollection, although the names of schools and people (with the exception of my first name) have been changed, as have some identifying details and place names. Some individuals are composites.

To my beloved husband, angelic son, and remarkable sister

with love

Dead Girl

It changed everything: a school picture printed on the front page of the

Elk Grove Courier

, the newspaper my father was reading. I was eight. Sitting across the breakfast table from Dad, I pointed. “Who is she?”

“She’s dead.”

He kept reading.

“What happened?” I asked.

No answer.

I leaned forward to get a closer look. She looked like me: same short cropped hair with razor-straight bangs, same heart-shaped face, same wool plaid jumper. I looked at Dad: bloated, smudged glasses slid halfway down his nose. Why wasn’t he telling me what happened? He loved talking gore; lived for it; documented it, even.

Dad drove his Ford pickup with his Kodak movie camera sitting shotgun just in case he saw an accident. If he was lucky enough to come upon something, he’d jump out and aim his camera at whatever was crumpled, bleeding, or burning. And every Thanksgiving he lined up Mom and the four of us kids on the gold-and-brown-plaid studio couch, hauled out the Bell + Howell reel-to-reel, and rolled his masterpieces.

Images jiggled past, scenes from our tiny Ohio town of Galesburg. Christmas morning, four beautiful children in color-coordinated Santa pajamas, squinting; summertime, my older brother Jamie’s first home run; a station wagon hideously wrapped around a telephone pole, blood dripping down the passenger door and plop, plop, plopping onto the road; my two older sisters and me in hats with wide ribbons hunting for Easter baskets; a dead cow smashed on the front of a Plymouth. Our childhood was preserved among the big fire at the Catholic church, a Greyhound bus accident on Fort Henry Road, and a tornado twirling up Martha Whitmore’s bean field. We all sat watching the movies and eating buttered popcorn made in the black-and-white-speckled pan that was always greasy, no matter how many times you scrubbed it. The disasters took up more reels than we did, and Dad narrated them like a pro.

So why was Dad skimping on the details about this dead girl? Maybe it wasn’t bloody enough for him.

I couldn’t get that school picture out of my head. I needed to know what had happened to that girl. If she was dead, something had killed her, and I wanted a heads up just in case whatever it was might be lurking nearby.

That night I casually swiped the newspaper off the cluttered coffee table and headed down the hallway to find my brother, Jamie. Nothing scared him.

He was sitting on his bedroom floor putting together a plastic model of a ’69 Shelby Cobra Mustang.

“Can you read this out loud?” I held up the paper.

“Why can’t you read it?” he asked, looking up from his project. He had most of the chassis put together.

“I

can

read it, but I want you to.” He stared at me. I held up a Milky Way left over from my Easter stash.

I couldn’t tell Jamie I didn’t want to read the details of that girl’s death by myself, especially with her staring out at me from the front page. I didn’t want him thinking I was chicken.

“It has to be right now?” he asked.

“Mom says I have to go to bed in a minute,” I said.

He twisted the lid back onto the blue-and-white tube of Testor’s glue and wiped his hands on the filthy dishrag he kept in his supplies shoe box.

“Let’s go,” he said. I followed him to the dark landing of our musty basement, where the four of us kids congregated for secret business.

“Here,” I said, handing him the paper and the candy. I was glad Jamie wasn’t too curious. He hardly ever asked questions about anything.

We sat crouched on the landing. I held the silver flashlight with the words “Black and Decker” printed down the side. Dad owned a hardware store in downtown Elk Grove and earned the flashlight selling ten hammers in two months, but he tossed it to me when the lens cracked. Jamie and I sat facing each other cross-legged with our foreheads touching, staring down at the white circle of light. He began to read: “‘Driver Faces Charges in Bike Rider Death’—”

“Bike rider? She was killed on her bike?” I craned my neck to see the paper right side up.

“Do you want me to read this or not?” Jamie tore open the candy bar wrapper.

“Go ahead,” I said, thinking of my own bike, a gold Schwinn with a leopard-skin banana seat. I’d spent hours running it up the wooden ramp Jamie had built beside the alley behind our house. Cars ripped through there without ever slowing down.

Jamie took a bite and began reading again: “‘Mason County’s fourth traffic fatality of the year occurred Tuesday afternoon with the death of Sarah Rebecca Keeler, eight-year-old daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Keeler.’”

Eight years old? I was eight. I grabbed the paper to take another look. She was my age, but I didn’t recognize her from school. I felt a pang of disappointment as I handed back the paper.

Jamie continued, “‘Sarah Keeler was a member of St. Mary Catholic Church and was a third-grade pupil at St. Mary School.’”

That’s why I didn’t know her; she was Catholic. Catholics were considered the equivalent of snake handlers in our small Ohio town. I didn’t know much about them except that they made Methodists like my parents nervous. This made Sarah more mysterious. Anyone who unnerved my parents was interesting to me.

“‘Sarah was en route on North Highway 26 when struck by a car driven by Nowell Linsley, sixty-one. The report states death was apparently instantaneous, due to a basal skull fracture and a broken neck.’”

“What’s a ‘basal skull fracture’?” I asked.

“I guess her head broke open,” Jamie said. He knew death. He’d buried dozens of small animals he’d found dead in the field behind our house, or cats and squirrels squashed by cars speeding through town on Highway 64.

I contemplated how hard I’d have to be hit by a car to have my head crack open like an egg. My oldest sister, JoAnn, had her head split open on the corner of the coffee table when we were little. Dad deliberately stuck his foot out and tripped her. He thought it was hilarious until bright red blood began trickling down her face.

I was trying to picture someone’s

whole

head laid open, hair and brains and blood on the asphalt, when I began feeling woozy and sweaty.

“Hold the flashlight still,” Jamie said. I shook my head and steadied the light. “‘A Breathalyzer test was taken on Linsley, and he was charged by the sheriff’s department for driving under the influence of alcohol.’”

“The guy was drunk,” Jamie said, handing me the paper. I thought of Uncle Ernie, the only person I’d ever seen drunk. He’d come to our front door one night after running down the street from the dilapidated Galesburg Tavern, where another drunk had been hitting him over the head with a pool cue. Dad wasn’t home.

Ernie’s forehead was bleeding and Mom looked pale and nervous, especially when he asked to use one of her good bath towels. The next morning I heard Mom call him a “sweet drunk,” so he’d probably never kill anyone on a bicycle. Even so, I’d be on the lookout for his white pickup.

That night I lay in my small wooden bed and relished the attention Sarah Keeler must have received. I fantasized that it had been me on that bike and I’d been struck from behind. I hoisted my arms above my head on the pillow and pretended to be lying on the road. In my fantasy my dad drove by and stopped, not because he recognized my bike (my dad had no idea what color my bike was); he stopped because it was potentially gory. He jumped out of the truck with his movie camera but realized it was me lying there—bleeding and dying.

Double jackpot

, he thought: one less mouth to feed

and

he’d get all the attention. People would feel so bad for him.

Dad resisted the urge to film the scene, opting instead to bend over my limp body, pretending to be struck with grief. He was surprised when he could actually squeeze out tears. Everyone closed in around him…and that’s when I canceled that fantasy.

If Dad shoved me out of the limelight even in my death scene, if he couldn’t even love me while I was lying on the asphalt, there was no hope.

Maybe others would have been sad to see me dead in the street. I thought of Mom curled up in the nubby orange chair reading

Rich Man, Poor Man

. Surely she’d have been devastated. But Mom was a human cork; she floated to the top of any awful situation. My mom, who’d told me the earth was flat, always created her own reality. She would have been fine.

I was beginning to wonder if dying was such a good idea.

It wasn’t as if I wanted to be dead; it was just that I was miserable and felt in the way most of the time. There was something wrong with me. I always knocked over my milk, I got sick every time we drove long distances in the car, and I wet my bed every night, even though I was in third grade. But when Dad started in on us, knocking Jamie across the kitchen and then kicking him in the side, or jerking my pants down in front of strangers, that’s when death seemed possible, even preferable.

If God could make me normal like everyone else in my class, or pull me out from under the rage of my own father, I might be happy instead of nervous and ashamed all the time.

I remembered the funeral details Jamie had read:

Friends may call on Saturday at Kilner and Sons Mortuary between 4:00 and 8:00 p.m. On Sunday there will be Mass at St. Mary’s, with burial following at Maple Creek Cemetery.

Until Sunday, when Sarah Keeler was sunk in a deep, lonely hole and the world forgot and moved on, I could pretend I knew her. I could wallow in the glow of her spectacular departure. Sunday was years away.

I woke up the next morning to sunshine and bushy green trees rustling outside my bedroom window. I rolled over and felt under my pillow for the newspaper. Still there.

I crawled out of bed to change my wet sheets and pajamas. Bed-wetting kept Mom from buying me a spiffy twin bed like the ones my older sisters, Becky and JoAnn, had.

Their fancy twins were on either side of mine, decorated exactly alike with smoky blue comforters trimmed in fluffy white ball-fringe. Their white wrought-iron headboards twisted into elaborate curlicues that mirrored each other.

My bed was narrow with white wooden rails that went halfway up on either side. The mattress was slick, quilted, and smelled of urine. It was a bed to be embarrassed by. A baby’s bed. A peed-in bed. I’d slept in it my whole life.

I walked into the bathroom and threw my pajamas and sheets into the tub.

I thought of Sarah Keeler as I looked in the mirror and imagined my own face on the front page of the

Elk Grove Courier

. More than anything else, I wanted to see her on Saturday between four and eight p.m. lying in her pink (I imagined my favorite color) coffin, her freshly washed hands folded over her lap, shoes double-tied for oblivion. I had to find a way to go to that viewing. And I knew the person to take me there was Granda.

Granda was my mother’s mother, but the opposite of my mom in every way. Granda was a realist, and that’s how she needed to be approached. She could be very sentimental and loving, but she’d also killed her own cat. He bothered her. She had a bad hip and she’d gotten tired of getting up and down out of her chair to let him in and out of the aluminum door of her trailer. So she’d locked him in her freestanding garage that the pole barn company had built for her right beside her trailer; she’d lured him in with a raw hot dog, closed the door, and left the Buick running for three hours.

I felt she could be persuaded to attend a funeral.

After breakfast I walked across Whitmore’s back field to Granda’s green-and-white double-wide. Granda was sitting at the kitchen table peeling new potatoes. I needed to be convincing but not too eager. I sat down across from her.

“A girl I knew died,” I said.

“Oh, honey, who was it?” Granda stopped peeling.

“It was in the paper yesterday.”

“That little girl on the bicycle?” she asked.

I nodded. I was glad I didn’t have to say her name as if I really had known her. “Mom doesn’t think I should go to the funeral home.” Granda started peeling again. “I feel like I should.”

“If your mom says you can’t, then you can’t.” Granda pointed the silver potato peeler in my direction for emphasis.

“Yeah, I guess so. The whole town’s going.”

Granda salted a piece of raw potato and handed it to me. I ate it slowly, the salt stinging my chapped lips.

“I was hoping maybe you could take me over there.” I looked at the table as my face flushed red.

“Honey, you don’t want to see that. It’s a terrible thing, very upsetting.”

“Well, I might go with Suzanne Beckner’s family, but I’d rather go with you. Mrs. Beckner said the entire county’s going.” I rested my hands on the table and put my chin on top. Granda was scrutinizing me.

“Didn’t that girl go to the Catholic school?”

“I guess so.”

“And you knew her?”

“Not very well,” I lied, “but enough to feel like I should go. Suzanne does too.” I ended with the one line I knew would really get her. “Mom can’t understand.” Granda prided herself on wholly understanding me.

She said she’d think about it, which was a good sign. When Granda had to think about something, it usually meant yes sirree. Besides, Granda rarely passed on any kind of local drama. It ran in the family.