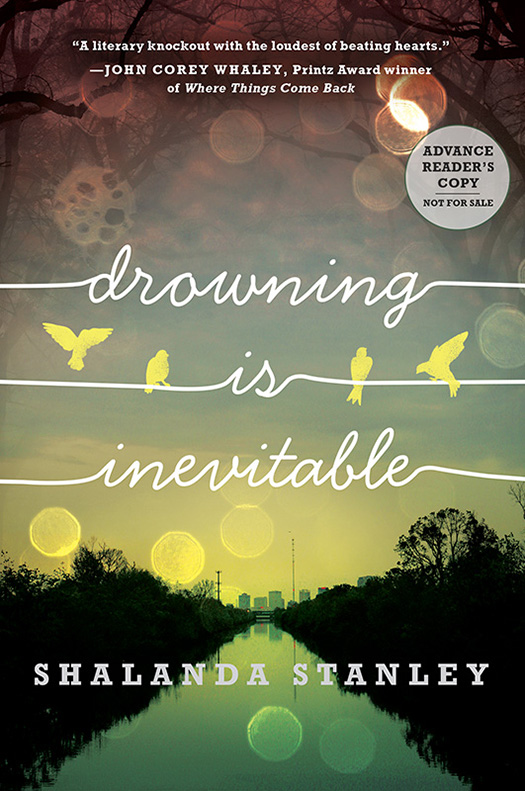

Drowning Is Inevitable

Read Drowning Is Inevitable Online

Authors: Shalanda Stanley

This is an uncorrected eBook file. Please do not quote for

publication until you check your copy against the finished book.

this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2015 by Shalanda Stanley

Jacket art copyright © 2015 by tk

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouseteens.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

tk

Printed in the United States of America

September 2015

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Random House Children's Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

I

think you've heard what happened. Most people have. We made national news. You don't know the truth, though. The newspapers didn't tell the whole story. They said horrible things about Jamie that I won't repeat. They said I made bad choices. But there are times in life when you tell your best friend you'll do anything for him, and you mean it. My dad says that's only true of high school best friends, and as I grow older, I'll realize there are things you shouldn't doâeven for a friend. I don't know about that, but I want you to hear the truth from me.

Forgive me for telling the parts you already know, but it's important to say everything. I should warn you, some of it might be hard for you to hear because of what happened on Fidelity Street. It'll be easier for me to tell you if we pretend we don't know each other, like this is a confession to a small-town priest.

St. Francisville, Louisiana, where I was on unofficial suicide watch, is hidden between green bluffs and the Mississippi River. I wasn't particularly sad about anything, but I was almost eighteen, and being that my mom killed herself on her eighteenth birthday, people were worried that suicide was genetic. To their credit, my life had paralleled my mom's up until I didn't get pregnant at seventeen.

My bedroom wasn't my own, but my mom's. It had stayed exactly the way she left it, down to my crib still standing in the corner. I sometimes thought about taking down her pictures and posters and putting up my own, or at least cleaning her clothes out of the closet, but it was easier to keep looking at her things. Now that I was her age and closer to her size, I even wore her clothes.

I hadn't always been allowed in her room. It was off-limits to me when I was younger, a shrine left untouched. I was eleven before I was brave enough to sneak inside, looking for answers to the questions I was too scared to ask. It was always in the middle of the night. I'd steal secrets from the folds of her thingsâher favorite CDs, books with highlighted passages that I'd read over and over by flashlight, too young to understand them but still searching between the words for clues to her. She was the ghost I was always looking for.

It was different now. I had open access, which in some ways was worse.

Standing in front of her closet looking at the proof that Seattle's fashion trends had once made their way south, Jamie said, “You'd probably have more friends if you stopped wearing your mom's nineties grunge clothes.”

It was true that I didn't have a lot of friends. Not because I didn't want more friends, but because everyone's parents remembered

her.

Apparently people were worried suicide was somehow both genetic and contagious at once. My mom was St. Francisville's only suicide. No one in town had died unnaturally since her, unless you counted the boating accidents, which nobody did. I guess death by boat couldn't be unnatural, seeing that the Mississippi River pressed against the town and the False River was just a ferry ride away. Drowning was inevitable.

“What good would changing my wardrobe do?” I said. “Nobody can tell us apart anyway.”

“You don't help,” he said. “Now come on and pick out something to wear tonight.” He yanked a flannel shirt off its hanger and threw it at me, but he missed and knocked a picture off my mom's dresser. It was one of her and my dad. Pictures of the two of them were all over the room. In almost all of them, he was looking at her instead of the camera, his love for her burning in his eyes. My mother was beautiful, and not in the all-mothers-are-beautiful way, but in the look-at-her, what-is-she-doing-in-this-town way.

“Fine, but it's too hot for flannel.”

Jamie looked back in the closet and smirked. “Good luck.”

I shoved him out of my way and snagged a dress off a hanger. “I'll be quick.”

I went into the bathroom to change. There were pictures of my mom and her friends stuck around the edges of the mirror. She was always smiling. She was a liar. Happy people didn't kill themselves. My dad said she had “a way” about her, said she had a way of believing in you so you felt like you were special. She could convince you to do anything with her eyes. She was beautiful, with poor impulse controlâa combination that did nothing but keep her in trouble.

My mom walked into the Mississippi River at night wearing only her nightgown. I was three days old. She didn't leave a note. Sometimes I followed her trail from the back door to the river, imagining which trees she might have touched, wondering if she paused before stepping into the water.

On coming out of the bathroom, I found Jamie flipping through her CDs. “We've got to get you some new music.”

Jamie was my favorite person in town and friend number one. He'd always lived next door, but we didn't officially meet until the first day of kindergarten, when he had been sporting an unfortunate shorn look. His mom had shaved his head to combat his obsessive hair twirling, a thing he did when he was nervous or sleepy. This had caused a huge problem at naptime, so I had scooted my mat close to him.

“You can twirl my hair,” I'd said.

He'd returned the favor by giving me his bag of chips at snack time, because my grandmother had forgotten to send me to school with a snack. We'd been taking care of each other ever since.

From that first day of school onward, we spent every afternoon playing together. What started as a friendship born of proximity became something deeper. Jamie never treated me like the daughter of the town's most infamous dead girl. He only saw

me.

He even let me keep his secrets.

When I was little, I used to pretend I was Jamie's sister, because I thought his family was perfect and I wanted to be a part of it. My grandmother's kitchen window looked right into their dining room, and I would watch them eating dinner, talking and laughing. His parents would look at him like he was the most important person in the world, and Jamie would look like he agreed. I'd watch them like they were a TV show.

But that was “BDD,” as Jamie would say. Before his dad became a drunk.

“We're gonna buy you some new music,” Jamie said. “Today. We fix this today.”

He pulled a CD out of the stack. It was The Smashing Pumpkins. “Here, put this in your box. This proves your mom had terrible taste.”

I looked everywhere for answers to the question of who she was. Some people collected rocks or stamps. I collected clues about my mother. I put everything in a box, a collection of evidence. Every clue was a piece of the mosaic I was building, hoping one day it'd reveal a clear picture of her.

Exhibit A: A newspaper clipping detailing a hunger strike she had organized when the Tackett boys didn't have money to pay for their school's hot lunches and the cafeteria lady had served them peanut butter sandwiches. She got all the other kids to agree not to eat until the Tackett kids could eat the regular lunch. It worked. Exhibit A showed she was kindhearted and passionate.

Exhibit B: A picture of her taken at Thompson's Creek, which had been stuck to her dresser mirror. She once went cliff diving there when the water was too low, and someone had taken a picture of her right before she'd jumped. On the back she'd written,

The rush was like nothing else.

Exhibit B showed she was impulsive and reckless.

I took the CD from Jamie. “I'll be sure to add this piece of information.”

Jamie nodded, his face serious.

There was a knock on the door. My grandmother stuck her head in the room. “Lillian, that other boy is here. He's on the porch. I told him you didn't want to see him, but he won't listen.”

“That other boy” was Max Barrow, my on-again/off-again boyfriend since sophomore year. My grandmother couldn't remember names. Jamie was “that boy” and Max was “that other boy.” By the way, my name isn't Lillian. Lillian was my mom's name. My grandmother started calling me it when I was in the sixth grade. At first it was a tiny slipup that she quickly corrected:

“Lillian, will you bring me theâI mean, Olivia, will you bring me the paper?”

Soon she was slipping up more and more. Then one night she caught me sneaking out of my mom's room, and the “Lillian” had escaped from her mouth in one loud breath.

Her eyes were distant with sleep. “What are you doing up? You couldn't sleep?”

I was scared stiff, unable to find any words. I braced myself for what I thought would be a verbal lashing for being in my mom's room. Instead, she reached for my hand and led me to the bed.

“Lillian, you need your rest.”

My grandmother had pulled back sheets and covers that had not been touched in eleven years and tucked me in snugly. She hummed a lullaby and rubbed her hand across my hair, and my eyes burned when she dropped a kiss on my forehead. Just like that, I became

her.

I didn't sleep that night. I thought about getting up and sneaking back to my bed, just pretending it hadn't happened. It was only a two-bedroom house, so I slept on a twin bed in the corner of my grandmother's room. I didn't budge, though, just stayed wide-awake in my mom's bed, under her dust-covered quilt, doing my penance. After that night, my grandmother stopped seeing me altogether: this was the consequences of my curiosity.

Jamie hated it.

“Her name's Olivia,” he said now.

He corrected her every time. It didn't make any difference. My grandmother would look at him with slightly unfocused eyes that never saw the things in front of her clearly, and go back to calling me Lillian.

My grandmother was old, but my dad said losing Lillian had aged her even more. She didn't have my mom until she was in her forties. They hadn't been trying for a baby. My grandfather didn't want kids. He was a traveling salesman who'd come through town and swept her off her feet. They got married, and he stayed for a few years, but he was a “wanderer,” according to my grandmother. He wandered into town and then wandered out of it. “He left me on a Tuesday,” she'd said. She found out she was pregnant a couple of weeks later.

“I don't like it when that other boy comes over, Lillian,” she said now. “He's no good for you. Boys like that can make a girl change her plans.”

That was funny, since the reason for our more recent breakup was that I didn't have any plans. My grandmother came into the room and picked up the shirt Jamie had thrown at me, then put it back on the hanger and hung it in the closet. On her way out of the room, she bent to pick up the picture on the floor. She put it back in the exact spot Lillian had left it in.

Jamie stared at the shut door for a time and then said, “You need to go talk to that other boy.”

“I don't want to.”

“Sure you do,” he said. “Go tell him you love him and you're ready to have his babies.”

“But I don't and I'm not.”

“You do love him.”

“I'm not ready to love him.”

“That's the first true thing you've said all day. Go ahead, go talk to him. I know you've already forgiven him.”

“How do you know?”

“Because you're always forgiving him for the wrong things.”

“Fine, I'll go talk to him.”

“Do you mind if I hang here?” he asked.

“No, of course not.”

These days, Jamie avoided going home at all costs.

Everyone

avoided going to Jamie's house. There were many reasons for this, the main one being that his dad was unpredictable. Jamie picked up the magazine on the nightstand and plopped down on the bed. It was a

Rolling Stone

from 1995.

“Cool, Soul Asylum is planning another tour.”

It was the June edition. I'd read it cover to cover. I'd read everything in the room cover to cover.

Max was sitting on the swing, his head in his hands. His clothes had that slept-in-look. At the creak of the screen door, he lifted his face to mine. Max was beautiful, in the same hard and brown way as a lot of boys in St. Francisville He was the size of a man, but when you looked in his eyes, a boy looked back at you. When he was near me, he made it hard to breathe. And not in that he's-so-dreamy-and-perfect way, but because he was the physical reminder of the last bad choice I made. He was the kind of boy you could make a lot of mistakes with. He was also magnificent and fearless. He loved me too much.