Dublin Folktales (19 page)

Authors: Brendan Nolan

The Phoenix Park bomb landed beside Dublin Zoo with its caged stock of wild and ferocious animals. There were no casualties other than broken sleep for humans and animals alike. There was general alarm that some of the animals at the zoological gardens had escaped into the public park under cover of darkness. The wild deer herd in the park numbered some 800 animals who roamed free throughout the park’s 1,752 acres. They might have provided sport for wolves, lions and leopards if they had departed their lodgings in the gardens. But the zoo’s perimeter held on the night, even when a maddened bison charged the restraining fence from within. Just the same, a few months later, in the month of August, the zoo’s council gave an assurance that all dangerous animals would be destroyed in case of an emergency, lest they escape into the park and the city.

If, for any reason, the Germans were to have returned to threaten Dublin, the zoo had, by then, gathered together a secret air force of budgies and parrots that could have been released to cause confusion in the heads of any amount of Luftwaffe air crews. Budgies and parrots had recently been brought to the zoo by their owners for sanctuary, which is where Ireland’s secret weapon comes into the story. Bird feed became scarce and hard to source in the wider community as the Second World War wore on, so where better to park pets for the duration of the Emergency than the zoo, where they would be fed and watered. In 1941, the year of the bomb, twenty-six budgies were donated by one person alone, while another bird lover brought twenty-four budgies to the zoo. Someone else handed over fifteen birds for safekeeping. It must have been a very noisy place when they were all housed and chattering away. They were there ready to answer the call to flight at any time. If there is one thing that would confuse a flying Nazi, it would be a Dublin budgie filled with the rage of the Dubs for a job badly done. It was not for nothing that German pilots might have warned one another to, ‘beware of the budgies of Dublin on the way to Belfast’.

The Nazi pilots might not have been able to see in the dark but they would still have been frightened by the flying budgies of Dublin.

M

ARSH

'

S

L

IBRARY

AND THE

R

UNAWAY

T

EENAGER

The ghost of Narcissus Marsh, a Protestant Archbishop of Dublin, is said to haunt Marsh's Library. The library is situated near the thirteenth-century St Patrick's Cathedral in the old quarter of the city, where his remains are interred. How this came about is a strange tale.

Narcissus Marsh was an Englishman who came to Ireland to work and never returned home. He was educated in Oxford and ordained in 1662. He was sent to Ireland as Provost of Trinity College Dublin in 1679. He never married and was to find the younger generation a trial, particularly his niece who it seems was to become the reason for his spectral nocturnal wanderings after his death.

While in his position at Trinity, he wrote that he was finding Dublin very troublesome, partly because of the multitude of visits the provost was obliged to carry out, and partly by reason of the ill-education that young scholars had before they came to college and were therefore both rude and ignorant. Perhaps the rudest of them all was his nineteen-year-old niece, Grace. After he had taken her in to his home, she had agreed to care of him in his old age, but then embarked on a course of independent action that vexed him sorely.

He was appointed Bishop of Ferns and Leighlin in 1683, Archbishop of Cashel in 1691, Archbishop of Dublin in

1694 and then Primate of Armagh in 1703. It was while he was Archbishop of Ireland that niece Grace struck out on her own in what was hardly an act of obeisance to such a powerful personage.

As provost of Trinity, Marsh had a new college hall and chapel built on the grounds and developed the college library. In a move to improve the efficiency of the library and its staff, Marsh insisted that when a new library keeper took up his position, an inventory of all books in his care must be presented. The following year, when a new keeper was appointed, the outgoing keeper and the new library keeper had to check that all listed books were there. If not, the outgoing keeper was charged to replace the missing books or pay in their value. Marsh acquired a good knowledge of the Irish language and encouraged the scholars to learn it. He appointed a native speaker as a lecturer to teach them the language of the country.

It was not until some twenty years later that the first public library in Ireland was built on the instructions of Archbishop Marsh and at his own cost. Designed by Sir William Robinson, it is still being used as a library 300 years later. While the books were displayed on the upper storey, the lower storey was designed as a residence for the librarian, who lived on the premises and both administered the library and defended it against any and all dangers that might present. He also made sure his inventory was correct at year's end.

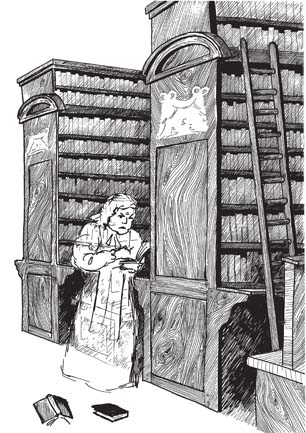

Through the library's early years, readers of rare books were locked into wired alcoves for security, while studying the valuable titles. Three of these cages remain as they were on the opening of the library. Many of the collections in the library sit on the shelves allocated to them by Marsh and by Elias Bouhéreau, the first librarian. Marsh's own collection of books was bequeathed to the library by a successor. Other librarians that followed continued the collection of suitable titles for the library. The present library contains more than

25,000 books in its catalogue from to the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, relating to medicine, law, science, travel, navigation, mathematics, music, surveying and classical literature.

It is said that the ghost of Marsh wanders about the library seeking one particular note in one particular volume. The incident that caused him so much angst in his living days occurred a few years before the library opened. So, it would appear that the note his ghost is said to seek is in a book that was in his possession before the library that bears his name was built at all.

Marsh had been appointed Provost of Trinity on the nomination of James Butler, Duke of Ormonde, Chancellor and Lord Lieutenant, who was the

de facto

ruler of Ireland in the king's name. Marsh resigned as Provost when he was appointed Bishop of Ferns. Narcissus, while still Protestant Archbishop of Dublin, lived as a bachelor in the Palace of St Sepulchre beside the Cathedral. He arranged for his niece, Grace Marsh, to take care of housekeeping for him. Grace bore the same name as Narcissus' late mother. Grace was aged nineteen and wished to enjoy life as a young woman might best do in seventeenth-century Dublin Church and academic circles. She may have found her new surroundings, lifestyle and the strict discipline of the archbishop's domain constricting and sought excitement from another gentleman of her acquaintance. For on 10 September 1695 Narcissus was discussing matters matrimonial with his diary. He wrote:

This evening betwixt 8 and 9 of the clock at night my niece Grace Marsh (not having the fear of God before her eyes) stole privately out of my house at St. Sepulchre's and (as is reported) was that night married to Chas. Proby vicar of Castleknock in a Tavern and was bedded there with him â Lord consider my affliction.

She was, according to Narcissus, married to Charles before they were bedded, and he was, it appears, an ordained minister of some Protestant persuasion, else he could not have married at all. The fear of God might be read then as fear of the archbishop as representative of God, a fear which Grace seemed to have had none of at all. Or perhaps, she believed that if she had informed Narcissus of her plan to marry the vicar of Castleknock the archbishop might have demurred. A popular twist in the story is that Grace left a note for her Uncle Narcissus in a book in his home before she eloped, telling him of her proposed course of action. But the learned man did not find that note in time, and never did, or so it would appear from his subsequent peregrinations through his huge collection of books.

The archbishop was to live on for a further eighteen years during which the story took another turn. Grace returned to live with him in his declining years, with or without Chas the curate we cannot say. Narcissus Marsh died on 2 November 1713 in his seventy-fifth year. Once dead, Narcissus began to haunt his library. The ghost is said to frequent the inner gallery, which contains what was formerly his own private library. The spectre moves in and out among the bookcases, taking down books from the shelves, and occasionally throwing them down on the reader's desk as if in passion, anger or frustration. Nonetheless, ever the neat scholar, he is said to always leaves the library in perfect order, when he is through with

his throwing. Some librarians occupying the rooms below believed in the ghost upstairs, others did not. Although such disbelief is subjective, for when one fears an unexplained movement or noise from above, it is difficult to shrug each time and say that it was nothing.

Grace, the runaway teenager of the seventeenth century, lived to be eighty-five years old. Her remains are buried in the same tomb as her uncle the archbishop. Which begs the question: why does Grace not just tell him in which book lies the note of elopement? If in fact there ever was such a note. What would she have done had her powerful uncle found the note and held her in the house while he had a word with the vicar from Castleknock about his marriage prospects? Then again, perhaps the ghost who shuffles through the library is not Narcissus at all. Perhaps it is the ghost of the unknown Dubliner. Whoever it is, the library was formally incorporated in 1707 by an Act of Parliament, a transcript of which reads:

An Act passed 1707 for settling and preserving a public library for ever in the house for that purpose built by His Grace Narcissus now Lord Archbishop of Armagh, on part of the Ground belonging to the Archbishop of Dublin's Palace, Near to the City of Dublin.

Amen to that.

F

ITS MAN

Bertie the baker lived on Dorset Street in the north of Dublin City. He was a generous person at heart and liked to help out his fellow man whenever he could. He was, however, a businessman first and foremost and he had to sell his bread and cakes at a profit. His customers knew this and graced him with their patronage. Bertie’s Bakery, with its small shop front, was willed to him by his father who started the business when Bertie was but a baby.

The shop prospered. Even people that had moved away to other places would travel to Dorset Street on Saturdays to buy Bertie’s brown bread to go with the weekend fry-ups. He found himself selling to the sons and daughters of the people that had bought from his father. But if he attracted the good customers, he also attracted the bad customers who moaned and complained about everything, in the hope that they would receive a discount or something for free. Usually Bertie made some little gesture to them when no one else was around. For he had learnt that such complainers were quite good customers if you thought about them in a different way. For them to have the right to make representations to him as the proprietor, they had to establish a relationship in the first place as paying customers. So, he would resist at first and then give in, saying that this was definitely the last time that this was going

to happen. Apart from their never-ending quest for a discount, they were excellent customers.

None of which went unnoticed by Charley the local fool who hung around the shop for the smell of freshly baked bread and the sight of the cakes in the glass-fronted display shelves. To look at him, you would not think there was anything amiss. Charley was a neat and tidy man, but that small piece of the jigsaw puzzle that creates a functioning mind was mislaid. Bertie tolerated, more than welcomed, Charley’s presence in the premises.

To remove Charley from the shop, Bertie occasionally asked him to do a small errand. Charley was always pleased to be asked. He always returned faster than Bertie would have thought possible or seemly. But since none of the people he sent bread or cakes to with Charley ever mentioned anything amiss, he continued to employ Charley in this way every now and again. This suited Charley, who was not a man that was in love with the concept of regular employment but who was pleased to serve as the baker’s ambassador as needs be.

One Saturday afternoon, as Bertie was winding up sales for the weekend, he asked Charley to deliver a special cake of brown bread to a gentleman that lived across the river on Eustace Street in Temple Bar. Off Charley went with the street address memorised in his head and a lift to his step. He was careful that one foot did not trip up the other on the way. It was the last time that Bertie could rely on Charley as a messenger. For Charley was the victim of a minor street riot that erupted on O’Connell Street following a protest march for something or other. Stones were thrown at the police for so long and in such a sustained manner that a snatch squad ran into the crowd to arrest the ringleaders, during which Charley received a blow of a baton to the head which felled him where he stood.