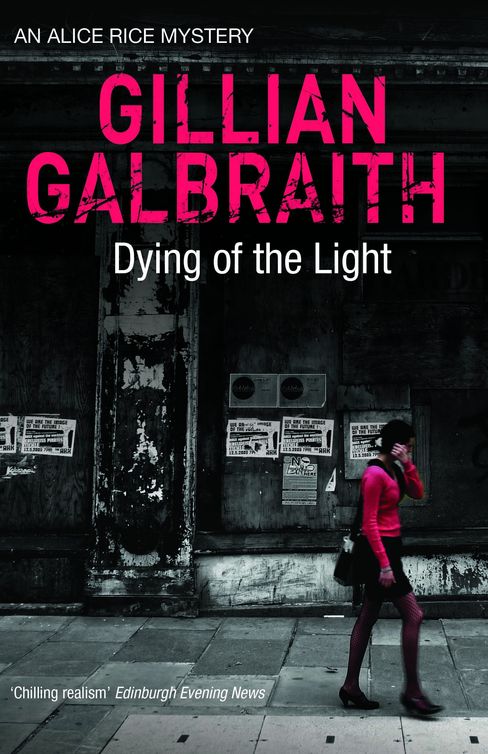

Dying of the Light

Read Dying of the Light Online

Authors: Gillian Galbraith

YING OF THE

L

IGHT

Gillian Galbraith

Maureen Addison

Colin Browning

Douglas Edington

Lesmoir Edington

Robert Galbraith

Daisy Galbraith

Diana Griffiths

Tom Johnstone

Johanna Johnston

Jinty Kerr

Dr Uist MacDonald

Dr Elizabeth Lim

Roger Orr

Aidan O’Neill

Dr Garth Utter

Any errors in the text are my own.

To my sister Diana, with all my love.

Annie Wright licked her parched lower lip. At the same time, she touched the packet of cigarettes in her pocket, stroking it slowly, as if to draw the nicotine into her system through her fingertips. A bead of sweat began to trickle down her spine until, deliberately leaning back against her chair, she allowed the material of her blouse to absorb it, bringing relief from its tickling descent. Looking at her shoes she panicked, realising she had made a mistake. They were too red, too shiny and the heels far too high. In a word, cheap. And what had possessed her to combine them with black tights and a skirt that did not even reach the knee? Sweet Jesus! She rose quickly, determined to leave, but before she had taken a step the door opened and a tall fellow, his black gown billowing in the draught, crooked his index finger at her, beckoning her to follow. As if in a trance, she did so.

Pushing the menu card to the side of his notebook in disgust, the Lord Ordinary waited patiently for the

witness

to arrive and the trial to resume. In the expectant silence a whispered conversation between two jurors became audible to him. Under all that horsehair, was his lordship bald? Casually, as if still absorbed in the business of choosing his lunch from the card, he tipped his wig to one side, revealing copious grey ringlets. Honour had been satisfied.

The sound of Annie Wright’s shoes as she clicked across the parquet to the stand transfixed everyone, and all eyes were on her as she teetered up the few steps

leading

to it. From her elevated vantage point she surveyed the courtroom and then, surreptitiously, stole a glance at the judge. His headgear appeared to be distinctly squint, its front edge at a diagonal rather than parallel to his

eyebrows

. As she turned to look at the faces of the jurors, an elderly man with food stains on his jacket gave her the slightest nod, but the others, heads bent as if scrutinising something on the floor, pretended not to have noticed her entry.

Suddenly, she became aware of Lord Culcreuch’s deep voice and forced herself to concentrate, raising her right hand as requested and repeating the words intoned before her. As she was mouthing them, their meaning sank in. The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. A noble enough sounding phrase, but one uttered only by fools and lawyers. In her experience, the whole truth rarely went down well, and even careful

approximations

of it cast her as less than human, someone unworthy of respect or sympathy. Scarcely a woman at all.

The first few questions asked by the Advocate-Depute, the prosecution counsel, were easy to answer, and she could hear her own voice becoming louder, more assured, as her confidence began to grow. And as the man

continued

to probe, turning now to the stuff of her nightmares, the chaotic mass of her recollection began to take on some kind of understandable shape. A proper narrative formed from the shards of memory that had been

whirling

around her brain for the past few months.

Yes, it had been dark, and yes, rain had been falling heavily. In fact, it had been bucketing down on Seafield

Road as she returned from the corner shop with the night’s tea, heading home, soaked to the skin and keen to get out of her wet things. Tam’s appearance outside the pub on the Portobello Roundabout had been welcome, he had shared his umbrella with her and his suggestion that they take shelter in his flat on Kings Road until the worst of the downpour was over had seemed a good one. So she had happily chummed him along as he wove his way down the street, joining in his beery rendition of ‘Flower Of Scotland’. The wine he had offered her had been welcome too until he had edged up the settee,

jamming

himself against her and putting his arm around her shoulder, hand dangling uninvited over her left breast. Tam was Thomas McNiece, the accused. The man sitting between the two officers.

The Advocate-Depute continued speaking,

questioning

her, and she managed to respond, but the description that she heard herself giving seemed to be of someone else’s experience, someone else’s ordeal. It concerned a woman who had been raped by a man she knew and considered a friend, her bruised body then hustled down the tenement stairs before being bundled out, like a bag of litter, onto the drenched street. A woman who had, somehow, got herself home, only to collapse outside her own front door.

As she spoke she glanced again at the jury box,

inadvertently

catching the eye of a well-dressed older woman, who was dabbing her eyes discreetly with a little white hankie. Annie Wright had not expected to evoke

sympathy

in anyone, and the sight of the lady’s tears surprised and heartened her. Maybe these people would understand after all. Maybe her own fears would be proved

groundless

, and the police sergeant’s prediction come true.

While she was distracted, gathering her thoughts, the prosecutor cleared his throat, keen to regain her

attention

, and start the ‘new chapter’ he had just promised the jury. And she knew exactly what it would be about, and prayed silently that it would be over quickly.

‘Now, Ms Wright, it may be put to you by Mr McNiece’s Advocate, that on the night in question you were working as, er… a sex worker… eh… a prostitute. What would you say to that?’

‘Eh… nah, I wisnae. I wis havin’ a nicht in… at hame, ken. I wisnae workin’ that nicht, I was spendin’ it hame wi’ ma lassie.’

‘But,’ the Advocate-Depute interjected, ‘you are a… sex worker? A prostitute?’

‘Aye.’

‘And you have told us already, I think, that you did not consent to having sex with Mr McNiece?’

‘Aye. It wisnae a job. He jist jump’t me.’

‘Did Thomas McNiece know what your job was, what you worked as?’

‘Aye. Tam kent.’

‘And on that night, did any money change hands?’

‘Fer Christ’s sake!’ she almost shouted, her voice tinged with despair, ‘I wisnae oan the job, ok? I jist telt ye. Tam jump’t me. He wis supposed tae be ma friend… ah, wis beggin’ him tae stop!’

She looked hard at the jury, defiantly, daring them to disbelieve her. But every face was turned downwards, studying, once more, the floor below their feet. No-one wanted to meet her eye.

Sylvia Longman QC, the Defence Counsel, stood up, hitched her gown onto her shoulders, and strode

purposefully

towards the witness box. She knew exactly how

the moves should go in this particular stage of the game, and had anticipated the Crown’s attempt to lessen the impact of the disclosure of the woman’s profession. They had raised the matter themselves to rob it of the shock value it might otherwise have had, in her skilful hands. An expected ploy, and one that would not succeed if she had anything to do with it. Conscious of the expectant hush in the courtroom, she began her performance by looking Annie Wright boldly in the face.

‘Ms Wright, would you be interested to know that the meteorological report for the night of Friday the fifth of October indicates only the presence of “light drizzle” in the Edinburgh area?’

The witness looked momentarily shaken, but managed to answer.

‘Eh? Well, a’ I can say wis that oan Seafield Road it wis pourin’ doon. Cats n’ dogs.’

‘Indeed?’ – a theatrical pause to let the doubt sink in – ‘and I think you have been a prostitute for about ten years or so. Is that correct?’

‘Aha.’

‘Thomas McNiece would know, of course, that you were a prostitute?’

‘Aha. I said he kent.’

‘And you also said that the two of you were friends?’

‘I thocht so. Aha.’

‘In fact, so friendly that I understand that you and he had a drink together before you went for your shopping?’

‘Aha.’

‘And the night of fifth of October you willingly accompanied…’

‘Aye! Accompanied!’ Annie Wright cut in, only to be interrupted in her turn by the languid tones of the lawyer.

‘If I might finish? You willingly accompanied Mr McNiece up the stairs to his flat?’

‘Aha, I said I done that, but I didnae expect him tae attack us!’

‘So. You both had a drink together. Then he invited you up to this flat, knowing that you were a prostitute, and you willingly accompanied him there?’

‘Aye.’

‘Mr McNiece will tell the Court that you, his friend, agreed to have sex with him.’

‘I niver done.’

‘And that you willingly did have sex with him?’

‘How come then I got they twa keekers tryin’ to fight him oaf?’ Annie Wright interjected angrily.

‘I was coming to that, to your “injuries”,’ the QC replied smoothly, brushing imaginary dirt off her fall. ‘Mr McNiece will maintain that after the sexual

intercourse

had finished you demanded money from him. He declined to pay you, no question of payment ever having been discussed between you beforehand, and you

physically

attacked him. In the course of defending himself he lashed out, accidentally hitting you on the face.’

‘Rubbish! That’s rubbish!’ The witness shook her head and then said, plaintively, ‘Miss, if it wisnae rape then why d’ye think I’m here, eh? Why’d I go along wi’ the polis an’ all?’

Sylvia Longman smiled. Things were working out

better

than she could have hoped. ‘Mr McNiece’s evidence on this matter’, she said, ‘will be that these proceedings, or at least your part in them, arise as a result of your desire for revenge. Revenge for the “freebie”, I think it’s called. What would you say to that?’

‘Me?’ the witness sighed, recognising defeat. She

tugged nervously on a chain around her neck, pressing a small, gold crucifix between the tips of her fingers. ‘Me? I’d say nothin’ to it. Nothin’ at a’. No point. Yous hae got it a’ worked oot.’

Only the well-dressed matron noticed the smirk that flickered momentarily across Thomas McNiece’s

features

. But the Judge immediately stopped his note-taking and replaced the cap on his fountain pen.

‘Ms Wright,’ he began in his sonorous baritone, ‘I need to be absolutely clear about this. Are you accepting

Counsel’s

suggestion that you complained about Mr McNiece raping you in order to get revenge on Mr McNiece?’

‘Naw, yer Honour. I wisnae the wan who reported it oanyway. It wis ma daughter, Diane. She got the

ambulance

an’ the polis came at the same time.’

Lord Culcreuch nodded his head. ‘So your position remains that you never consented to sexual intercourse with the man?’

‘Aha.’

‘And that no question of payment by him ever arose?’

‘Aha.’

‘And your explanation for your injuries is what, exactly?’

‘Like I said. He belted me when I wis tryin’ to get him oaf o’ me. He slapped me, ken, richt across ma face.’

The older lady, Mrs Bartholomew, listened intently to the Judge’s charge to the jury. Only with such

guidance

would she be able to discharge her duty properly. Conscientiously. The onus, or burden of proof, it had been explained, was on the Prosecution to establish beyond reasonable doubt, that the accused had engaged

in sexual intercourse with the witness and without her consent. And after three whole days of listening, she thought, three utterly exhausting days, they had better get it right. Of course, it was far too late now. She had already missed her own ‘surprise’ birthday party, not to mention the promised theatre matinee. So, justice had better be damn well done.

Out of the corner of her eye, she caught sight of her closest neighbour doodling on a notepad. Some kind of motorbike or push-bike or other wheeled thing. Well, really! The lad looked too young, too immature, to be on jury service, fulfilling an important civic duty, and now appeared to be wilfully deaf to the guidance issuing from on high. Before she realised what she was doing, she

surprised

herself by releasing a loud ‘Tut, tut,’ only to be met with an amused grin and the closing of the pad.

Neither the dry address delivered by the Prosecutor nor the emotional appeal made by the female QC

clarified

anything for Mrs Bartholomew. And no wonder, she thought. She had, after all, heard all the evidence for

herself

, already formed her own impressions of the witnesses and knew exactly whom she believed. And, as importantly, whom she did not. But, of course, one could not be sure. How could one be unless one had been in the very room, at the very time, with the two individuals concerned? Had she been in the victim’s unhappy predicament she would have tried to fight off the Neanderthal and sustained bruising, abrasions and so on at his hands. A creature, she noticed, now so relaxed, that he appeared to be dozing during his own trial.