Dynamic Characters (22 page)

Read Dynamic Characters Online

Authors: Nancy Kress

THE DESIGNATED READERS:

WHAT AUDIENCE ARE YOU WRITING FOR?

Your intended audience is probably the most important factor determining how unsympathetic your main character can be. Certain kinds of commercial fiction—romance, ''cozy'' mysteries, romantic suspense, young adult—demand a sympathetic protagonist because of the identification phenomenon mentioned above. ''Literary'' fiction, however, which frequently aims to examine its characters rather than encourage identification with them, allows much more unpleasant protagonists. Even so, Thackeray, a very popular author in his day, was widely criticized for creating Becky Sharp. She was seen as an unflattering portrait of sacred womanhood. And Toni Morrison has not escaped criticism for providing very few portraits of black men that any black male reader would want to identify with.

The bottom line here is that your chances in commercial fiction are better with a sympathetic protagonist. You can save the unsympathetic characters for secondary roles. Until the movie version of his novel

The Silence of the Lambs,

Thomas Harris did not sell anywhere near as many copies—by an order of magnitude—as Danielle Steel, whose most prominent characters are always sympathetic. At the other end of the literary spectrum, the ''little'' magazines often seem to me to be bored by ordinary, nice, loving people as protagonists. Know your prospective audience when you plan your unsympathetic character.

THE NOVEL'S EYES: IS YOUR UNSYMPATHETIC PERSON THE ONLY POV CHARACTER?

It's easier to pull off an unpleasant protagonist if somebody more sympathetic is the POV character. This gives the reader someone else to identify with. For instance, we see Captain Queeg's story through the eyes of a likable young officer on his ship.

In a novel, you can also try a multiple POV. The amoral Becky

Sharp shares her multiviewpoint novel with the saintly Amelia Sedley. On the other hand, George Babbitt is both protagonist and POV character in his eponymous novel. However, Sinclair Lewis tells the story from a great enough distance, and with enough authorial comment, that we don't feel we're locked into this dim and tedious man's head all the time. The author becomes a second POV.

Can you tell your nasty character's story just as effectively from another POV, with a shared POV or using a fairly distant third person? Will what you lose in immediacy be redeemed by a more balanced perspective—and by some reader distance from a distasteful mind? Only you can make that decision.

THE ACCEPTABLE LIMITS: IS YOUR CHARACTER JUST TOO NASTY TO BE BELIEVABLE?

Sometimes the problem with an unsympathetic character isn't that she's a bitch but that she's not a believable bitch. Losers have just as complicated motives as anybody else. Bitter old women get that way because of real-life events. Children who pull wings off butterflies may be fiercely loyal to a friend or a pet dog. Ask yourself whether your unsympathetic character might become more plausible if you showed us her softer side, her history or her inner beliefs. Even if we still don't like her, believability may make us more willing to hear her story.

THE BIG CHANGE: WILL YOUR CHARACTER BECOME MORE SYMPATHETIC BY THE END OF YOUR STORY?

Many readers are willing to accept an unsympathetic protagonist if they sense that during the course of the story he's going to change. A character who learns great truths and becomes more human as a result can make a satisfying tale. I did this in my science fiction story ''Mountain to Mohammed,'' in which a young doctor works illegally among the uninsured poor for the danger, self-aggrandizement and thrills. Only after he gets thrown out of the medical establishment does he realize the real rewards of practicing medicine.

To pull this off, your character has to be deluded or callow, not genuinely nasty, or the change won't be believable. Even so, you'll lose some readers unwilling to stick with the story long enough to discover that the protagonist changes. At least one reviewer has compared ''Mountain to Mohammed'' unfavorably to some of my other work because of its ''unappealing protagonist.''

JUST DESERTS: IS THIS A COMEUPPANCE STORY?

Many readers like stories about distasteful people—provided they get squashed in the end, restoring moral order to the universe. When the distasteful person is the protagonist, however, and not merely a supporting character, there are two pitfalls for the comeuppance story.

One is that, as with the protagonist-who-changes story, readers may not stick around long enough to find out there

will

be a comeuppance. To ensure they do, you have two choices. You can signal from the beginning that your unsympathetic protagonist not only is riding for a fall, but will get it. Do this through a prologue that hints at the ending, or through making it clear that the author also dislikes the villain, or through telling the story as a flashback, with the comeuppance a settled thing.

Or, you can make your unsympathetic protagonist seem harmless for the first part of the story, so that by the time we realize he's unsympathetic, we're already hooked on finding out what's going to happen. The second choice is more common.

A classic example is Edith Wharton's short story ''Roman Fever.'' In the beginning its two middle-aged widows, Mrs. Slade and Mrs. Ansley, seem equally benevolent. They watch their two daughters, brilliant Barbara Ansley and mousy Jenny Slade, go off for an afternoon of pleasure in Rome. But as the ladies reminisce, we slowly realize that Mrs. Slade is an amoral and jealous woman who, twenty-five years ago, tried to have her friend killed because Grace Ansley was in love with Alida Slade's fiancee. Mrs. Slade mocks her friend, reminding her that Delphin Slade loved her and not Grace, that ''I had him for twenty-five years, and you had nothing but that one letter he didn't write.'' She bullies Grace and admits she hates her, even though she believes Delphin never cared about Grace. It isn't until the last line of the story that Mrs. Slade gets her comeuppance: Taunted with having nothing of Delphin, Grace Ansley says quietly, ''I had Barbara.'' It's a quietly devastating line.

The other danger of the comeuppance story is that it can seem contrived. Every adult knows that the universe doesn't always punish the bad guys. So if your universe is doing just that, it must seem to grow naturally out of the human forces opposing your bad guy, and not just from the author's desire to provide moral justice. Your unsympathetic character must stumble because he's too shortsighted or too ambitious or too cold to understand other people's strengths and alli-ances—not just because he's doing unsympathetic things.

THE STINGING EXAGGERATION: ARE YOU TRYING TO MAKE A BITING POINT ABOUT THE WORLD?

Sometimes the unsympathetic character isn't actually the protagonist; his world is, and he exists mostly to direct our attention to it. In this case, if the texture of the world is compelling enough, or relevant enough, or horrifying enough, many readers (not all) will accept the unsympathetic protagonist as an inevitable product of the environment you're showing them.

Consider two very different examples. George Babbitt, an uninteresting man in himself, succeeds as a character because Sinclair Lewis uses him to hold up a mirror to the (then contemporary) world of small-town American business. Lewis's aim is to show how boring, petty, stifling and mean-spirited that world was. Babbitt is its emblem, but it was the portrait of a way of life that made the book so hotly controversial, so much discussed—and so successful.

Similarly, Harlan Ellison's science fiction story ''A Boy and His Dog'' features a protagonist, Vic, as horrifying as Hannibal Lector— and for much the same reasons. But Vic is the logical product of a horrifying future, and that future is both the story's justification and its real protagonist.

A FINAL GOOD JUSTIFICATION FOR MR. REPULSIVE: DOES HE HOLD US RAPT?

This is the bottom line: If your character is unpleasant, unrepentant, unpunished, implausible, and atypical, is he just so sheerly fascinating that we'll want to read about him anyway? If so, it won't matter that he's unsympathetic; the story or book will sell. But he'd better be

really

fascinating.

And there's another caveat here: What's fascinating to one person may not be to another, no matter how well written. Case in point: Bret Easton Ellis's

American Psycho,

told from the POV of a psychopathic serial killer. The first publisher, alarmed by adverse publicity, dropped the book. But when it eventually came out, a great many people found the profoundly unsympathetic protagonist fascinating enough that they read the novel. Many others did not. Similarly if less dramatically, many readers praised John Updike for his four-novel series about Rabbit Angstrom, who is crude, selfish, misogynistic, and irresponsible. Others have disliked Rabbit from the beginning, refusing to spend one entire book with him, let alone four (one early reviewer called Rabbit ''repulsive''). It's worth remembering that

unsympathetic

and

fascinating

are both subjective terms.

THE LAST WORD: TRADE-OFF

To return to the bewildered writer's question:

Can

a story or novel survive if the main character is disliked? Yes. Not only survive but flourish, provided the story gives us something else—perspective or change or justice or point or sheer fascination—to offset our dislike. As with so much else in writing fiction, an unsympathetic protagonist is a trade-off. Are you gaining more than you're losing?

If so, you don't have to invite him to dinner. Celebratory cocktails— say, in an editor's office—are quite enough.

SUMMARY: CREATING DISTASTEFUL PEOPLE WE'LL HAVE A TASTE FOR

• Unsympathetic protagonists work best in ''literary'' fiction, while unsympathetic secondary characters are a staple of commercial fiction. This is even more true if the unsympathetic protagonist is also the POV character.

• Unsympathetic characters need to be as fully developed as likable ones. Nastiness is not, in and of itself, sufficient characterization.

• In fact, unsympathetic characters probably need to be even

more

interesting than sympathetic ones, since the writer loses the interest-garnering technique of reader identification.

• If unsympathetic protagonists are going to get a comeuppance at the end, either disguise their nastiness early on, or hint that this is a just-wait-he'll-get-his story.

• If an unsympathetic protagonist is used to make a comment on a particular time and place, make sure the connection is very clear from the beginning.

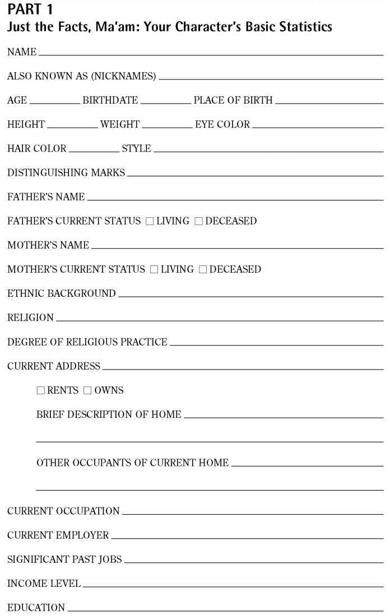

FBI agents need to know everything they can about the people who are key to their cases. So do novelists.

The FBI meets this need by keeping intelligence dossiers, adding to each as new information becomes apparent. Some writers do the same thing. They write biographies of their major characters before starting a book, add to these during the writing and refer to them often. To other writers, this whole idea is horrible. These are the seat-of-the-pants writers who rely on intuition, moment-to-moment inspiration and surprise to construct believable and interesting characters. They also rewrite extensively on the second draft, since they change their minds so often during the first one.

It doesn't matter which kind of writer you are. Different methods work for different people. But if you are the methodical, preplanning type, you might find this chapter useful before you begin writing a book. If you are the flying-blind type, this chapter can be used after you've finished the first draft and are ready to reconcile all your course changes into a single smooth trajectory.

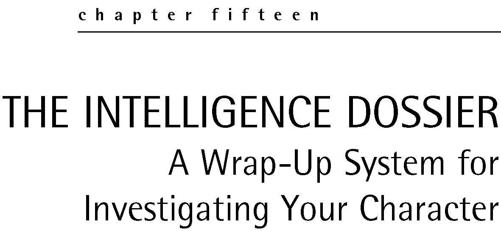

What follows is one way to better understand your character: the dossier. It covers information that you should know about your protagonist, and probably should know about the other major characters as well. Different sections of the dossier concentrate on different kinds of knowledge. All sections have the same goal: to stimulate your thinking about your character. You may do only that with the dossier: think about some section(s) of it. Or you may decide to photocopy some, all or none of the sections as they seem to apply to your particular characters in your particular book, and fill them out. If you do, keep them for later reference.