Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir (17 page)

Read Dynomite!: Good Times, Bad Times, Our Times--A Memoir Online

Authors: Jimmie Walker,Sal Manna

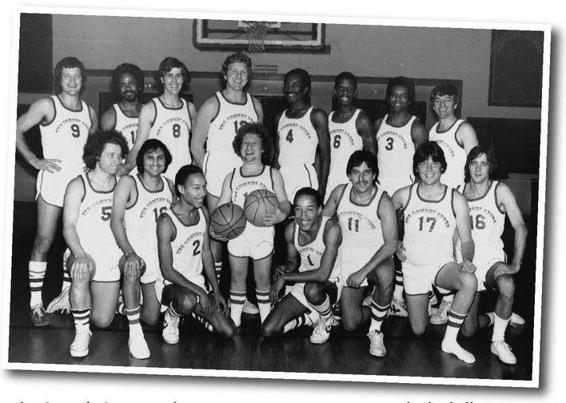

The Comedy Store Bombers, 1978. We were a very serious basketball team, as you can see by our center, Corky Hubbard, holding the basketballs. Standing (left to right): David Letterman, Tim Reid, Lue Deck, Big Roger, Darrow Igus, me, Johnny Witherspoon, Tom Dreesen. Kneeling: Jimmy Heck, Joe Restivo, Daryl and Dwayne Mooney (aka The Mooney Twins), Roger Behr, Jimmy O’Brien, Bobby Kelton.

Courtesy Jimmie Walker

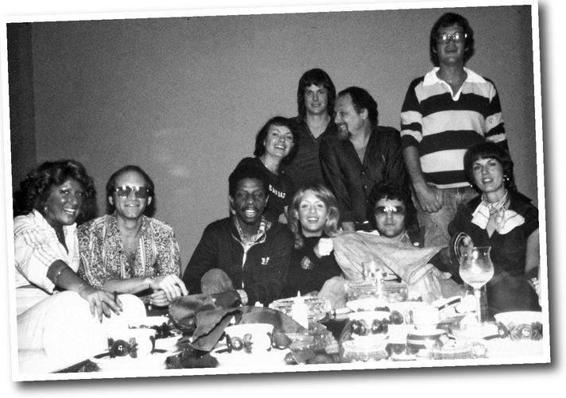

Friends and others, circa 1976. Seated (left to right): Elayne Boosler, Gene Braunstein, me, Adele Blue, Jay Leno, Michelle Letterman (Dave’s wife). Standing: Helen Kushnick, Wayne Kline, Budd Friedman, David Letterman.

Courtesy Jimmie Walker

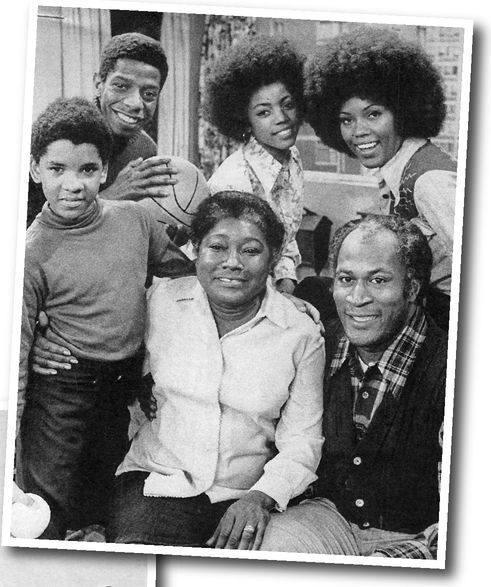

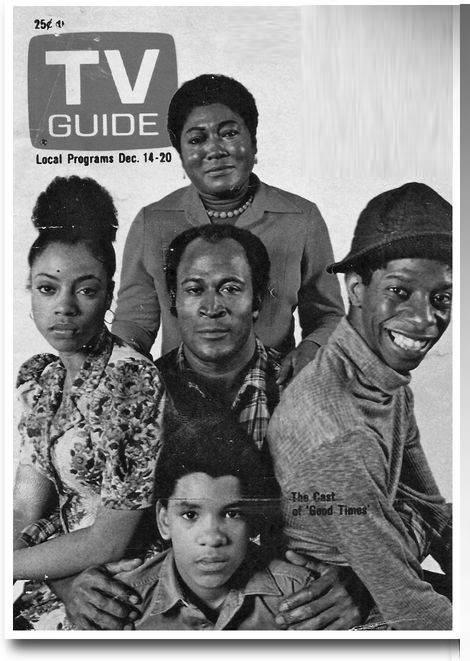

One happy family on

Good Times

with the original cast. Top row: Me, Bern Nadette Stanis, Ja’Net DuBois. Bottom row: Ralph Carter, Esther Rolle, John Amos.

The only one who seems to be really happy is me!

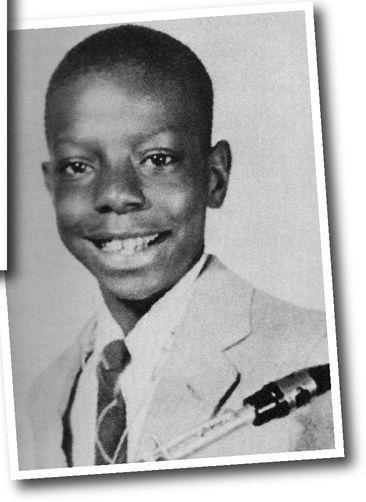

Sax with his beloved sax, which I still have today.

Courtesy Jimmie Walker

You have to wait forever to see a doctor. Had the forty-eight-hour virus. Went to see my doctor. It cleared up in the waiting room.

(February 8, 1976)

Unusual for Letterman would be a sex joke, such as this one:

The University of Washington conducted a study that proved girls with big chests get more rides when hitchhiking than flat-chested girls. Used to be all you needed was a thumb. Now you’ve got to have two handfuls.

(February 8, 1976)

Occasionally he offered a joke that embodied that sharp wise-ass attitude of his, a joke that would probably kill on his show today:

I love professional golf. Only game in the world where a guy gets applause for his putts.

(February 8, 1976)

Leno, his idol, rarely submitted any jokes. He would riff on the fly or comment about someone else’s joke. He and Mitch were like jazz musicians, playing off the other instruments. Leno was the absolute best punch-up comic. Many times a joke would be close but not quite there. Something would be missing or needed to be tweaked for it to work. Jay was a master at that. He could save a joke like no one else.

However, Jeni and Schimmel were not enthusiastic about writing for me and did not contribute much at the meetings. But they needed the money. That was okay; I was doing well. If I could help them feel as though they were in show business and keep them from having to take a day job, then I was glad to do that. Sometimes, when they needed it, I would just give them $100. I considered it an investment in my career, one that might pay off later. Sometimes, such as when Schimmel needed money to help pay medical bills for the birth of a daughter, it was just the right thing to do.

Jeni was one of the best stand-ups comedy has ever had. Schimmel wasn’t far behind, with a stunningly outrageous and explicit act. They thought, why are we writing for this guy? We’re better than he is! Schimmel would tell me, “I’m writing jokes for J. J.? I’m not doing any fuckin’ dyn-o-mite stuff!”

Louie Anderson was among my second wave of writers, but he was reluctant to come on board because he did not consider himself a joke writer. His style was closer to that of Cosby—more a storyteller. Mitzi Shore, who ran the Comedy Store, didn’t think he was much of a stand-up at all and refused to put him in the line-up. “He’s just a fat guy,” she said. “I can’t stand the fat stuff. All he does is the fat stuff and I can’t stand the fat stuff.”

I knew Louie was better than that, so I encouraged him to focus more on his stories about his large family and growing up in Minnesota. When he was ready, I forced Mitzi to watch his act again. The next week Louie became a regular. He would later pay it forward when he discovered Roseanne Barr when she opened for him in Denver. I then suggested to Mitzi that she team them up at the Comedy Store’s new room at the Dunes in Las Vegas. Both became major stars.

I had a few women comedy writers on staff, though Boosler, my all-time favorite female stand-up and a friend from the New York Improv days, was the only one of note. Without question, the women had the dirtiest, funkiest jokes. When they told them, all the guys would cringe. One of Boosler’s more mainstream lines was:

Some guys expect you to scream “You’re the best” while swearing you’ve never done this with anyone before.

Byron Allen was one of the black writers on my staff and the youngest of anyone. He was only sixteen years old. Wayne Kline had seen him perform at the Store, told him I was looking for people to write jokes, and invited him to a writers’ session. He came with his mom! He pitched and pushed his jokes like everyone else—while his mom waited patiently in my kitchen.

Teachers always say if you cheat you only hurt yourself. I say, “That’s okay, I can take the pain.”

(Byron Allen, date unknown)

The best pure joke writers were not performers: Wayne Kline aka Wayne Wayne the Joke Train and Steve Crantz.

When Wayne entered the room, everyone thought, “Oh shit. We can’t beat this guy.” He was so fertile that if you said, “I need a couple of jokes on trees,” he would ask, “The bark or the root?” Among his contributions at the meetings:

Black folks have a hard time getting credit. The first question they ask is, “Is this the first time you’ve been turned down for credit?”

(December 10, 1975)

I love to watch how men pick up women. Some guys are so uncool. You know how guys brag they never paid for it? I’ve seen guys out there look like they never got it free.

(March 26, 1976)

Used to be black folks couldn’t get jobs. Now look in the paper. They got ads just for us. Wanted: bright industrious black college grad. Must have own shovel.

(April 14, 1976)

Steve Crantz was even more prolific, as if that were possible. I met him via fax. He was about twenty-four years old and living in Pittsburgh with his parents. He faxed me a few jokes and I used them. He also sold jokes to Joan Rivers and Rodney “I Get No Respect” Dangerfield. Rodney used this one from him:

Oh boy, everybody’s got a family stone. I found out what my family stone was. My family stone was gravel.

Crantz would send me fifty jokes—not a week . . . a day. No other writer would do that. He was amazing. Finally I asked him to come out to Hollywood to write for me and travel as my road manager. He was hesitant because he had never been away from home. But I had my lawyer, Jerry, call his dad, Dave, and assure him that Steve would have a place to live and be taken care of. When he arrived, I put Steve up in an apartment and gave him the use of a car.

The first time he came to a writers’ session he fit right in. He was so funny, and he was funny all the time. His business card read: “Comedy Writer . . . I buried more people than Forest Lawn.” He was a joke writer, not a sitcom or movie scriptwriter, not a performer. But he was so gregarious—talking all the time—that some people thought he was doing an act. He even looked offbeat—short and, though a young man, completely prematurely gray, and he was a chain smoker, two packs a day. He was totally out there, always “on.”

Because he talked constantly, was always doing jokes, having Steve on the road was great because he took the pressure off me. I could just sic him on whoever was talking my ear off, and pretty soon they said, “Okay, I gotta go.” But as much as Steve disliked living in LA—it was way too different from Pittsburgh for him—he hated being on the road even more. Two days here then move, one day there then move—that was not a lifestyle he enjoyed. Also, when he was away from LA, he was worried about everything—his apartment near Hollywood Boulevard, his car, anything, and everything.

Most of all, he deeply missed his family. After he was in LA a few months I took a call from his dad. He told me that Steve was afraid to tell me that he had moved back to Pittsburgh the previous day. Steve wanted me to know that he had left the keys to the car in the apartment and that the door was unlocked. Obviously, Crantz and LA were not a match. When I finally talked to Steve, he wondered if it would be okay if he sent me jokes once in a while. I said, “Of course.”

Along with traditional comedy writers like Crantz, I wanted wildman comics like Allan Stephan, Jeff Stein, and Mitch Walters at the meetings. I needed to hear that voice of craziness, people who would break the rules, even mine.

A couple of oddball Jeff Stein jokes (dates unknown):

I travel a lot . . . tried to save some money . . . took one of those no-frills airline flights. It was terrible—they made me row!

I meet some strange girls. I asked a girl out the other night and she asked if she could bring a friend. I said, “Sure.” She brought her probation officer.

I needed to hear what was wrong for me, too outlandish for me, so I knew not to go there. Allowing that spectrum in a meeting was important because if I didn’t, I would never know what was being done on the sharp edges of comedy, even if that was not a place I wanted to go. I also needed a voice of reason in the room, like Mister Geno or, later, Jimmy Brogan, who understood comedy and I could trust to say to a writer, “Love that but, really, no.”