Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (35 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

The result of this order was a division of authority and inevitable friction. Indeed, the Reichsmarschall refused to delineate their authorities. Now, however, Udet’s huge agency had to have Milch’s cooperation to function. Friction increased, and so did the pressure on Udet.

Hermann Goering still cared for his old friend, however, and in August, 1941, advised him to go on a vacation. He even invited Udet to spend some time at his luxurious hunting lodge, Rominten. Udet, however, had lost interest in hunting and on August 25 checked back in to Buehlerhoene. He did not return from leave until September 26.

26

While Udet was gone, Milch continued his relentless drive to gain power at Udet’s expense. On September 7, he gained the authority to reorganize the Technical Office and the Office of the Chief of Supply and Procurement. Two days later, Milch fired

Generalingenieur

Tschersich. Later that month he dismissed Reidenbach and relieved Ploch, who was sent to direct Air Administrative Command II in Russia. Ploch left for the eastern front on October 1, 1941.

Meanwhile, Milch took energetic measures to put the air industry back on a firm footing. He ordered Albert Speer, the Fuehrer’s architect, to construct three aircraft factories at Bruenn, Graz, and Vienna. They were to be as large as the Volkswagen Works. He gave Speer eight months to complete them. Milch also reorganized the aircraft industry, put an end to trade secrets, reorganized Udet’s office, and, to reassure himself of the Reichsmarschall’s support, christened the whole project “the Goering Program.”

On October 4, 1941, a week after he returned from leave, Udet was forced to officially approve the new organization of his agency. There were to be four office chiefs: Col. Wolfgang Vorwald for the Technical Office, Maj. Gen. of Reserves Baron Karl-August von Gablenz for the Air Force Equipment Office, Ministerial Director Hugo Geyer for the Supply Office, and Ministerial Director Alois Czeijka for the Industrial Office. “By this time it was all over for Udet,” Colonel Pendele remarked later.

27

On November 15 General Ploch, on leave from the eastern front, visited his old chief. He told Udet about the mass murder of Jews in the East. Udet was terribly upset.

28

Whatever else he was, he was no monster.

Two days later Udet drank two bottles of cognac and telephoned his mistress, Mrs. Inge Bleyle. “Inge,” he said, “I can’t stand it any longer. I’m going to shoot myself. I wanted to say goodbye to you. They’re after me!”

29

She was still trying to talk him out of it when he pulled the trigger. He left behind a suicide note to Goering, asking him why he had surrendered to “those Jews,” Milch and von Gablenz.

30

Over the wall of his bed he had scrawled in red crayon a note to Goering: “Iron Man, you deserted me.”

Udet was officially reported as having been killed in a crash while testing a new airplane. Goering wept openly at his funeral, but later (on October 9, 1943) he said: “If I could only figure out what Udet was thinking of! He made a complete chaos out of our entire Luftwaffe program. If he were alive today, I would have no choice but to say to him: ‘You are responsible for the destruction of the German Luftwaffe!’”

31

Goering blamed Udet for the technological failure of the Luftwaffe, but he must share much of the blame himself, as his own people told him. In February, 1942, an investigation was launched against Ploch, Lucht, Tschersich, and Reidenbach—Udet’s chief of staff and his leading engineers. The investigation was headed by Generalrichter Dr. Kraell and Col. Dr. Manfred Roeder, both of the Judge Advocate’s Branch. It was stopped in the summer of 1942, twice resumed, and twice halted again. There were no indictments and no trials for four major reasons: first, the Luftwaffe General Staff could not be absolved of responsibility, because it had neglected to see the problem, apparently due to a lack of interest; second, there was no way to avoid implicating leading aircraft designers and industrialists; third, there was no evidence of criminal intent; and fourth, Goering himself would be implicated for having neglected his supervisory responsibilities.

32

The investigation was quietly dropped.

Milch succeeded Udet in all of his offices. He cut Udet’s 4,000-man staff by 2,000 men, removed the inefficient, cut out numerous useless projects (including the Me-210), streamlined the bureaucracy, cut paperwork in half, and improved production remarkably. Realizing that, despite the assurances of Dr. Koppenberg, the Ju-288 (or “B Bomber,” on which the General Staff placed great hopes) could not possibly be ready before 1944, he prevailed on Goering to cancel it, which he did in late 1941. Shortly thereafter, Milch sacked Koppenberg altogether. Because he realized that obsolete airplanes were better than no airplanes, the state secretary further decreed that existing aircraft be continued in production until their replacements were ready. He also called for the adoption of total war measures, but this recommendation was rejected by Hitler. Under Milch’s capable and ruthless leadership, aircraft production began to rise again in 1942.

33

Nevertheless, Milch was not able to make good five years lost to incompetence and neglect overnight. He faced the same problems Udet had, plus he had to straighten out Udet’s mess. He had to deal with a shortage of raw materials and the manpower drain to the eastern front, which made it impossible to demobilize workers for the aircraft industry, as Hitler had planned. He also had to compete with the other services—the navy, SS, and army—for resources and money, at a time when the fighting (and the manpower and equipment losses) on the eastern front was near its peak. Due to the needs of the armies in the East, the Luftwaffe lost its number one priority in raw material allocation. After he was captured in 1945, Gen. Karl Koller complained: “Air armament was placed way down the list; first were submarines, then tanks, then assault guns, then howitzers, and Lord knows what, and then came the Luftwaffe. We were smothered by the enormous superiority of Allied material, because the German High Command undertook too much on the ground in the East, and because it did not direct the main weight of armament right from the start toward air supremacy.”

34

As a result of the chaos in the Technical Office and of the shortage of raw materials, aircraft production in 1942 was only 32 percent above that of 1941,

35

and many of these were obsolete models. Britain had surpassed Germany in aircraft production in 1940, and Russia had done the same in 1941, if not before. On December 11, 1941, at the request of the Japanese government, Hitler declared war on the United States—the nation with the greatest industrial potential in the world. It did not take a genius to see that the handwriting was on the wall for Germany and the Luftwaffe.

An aerial photograph of Stalingrad after it had been pounded by the Luftwaffe, 1942.

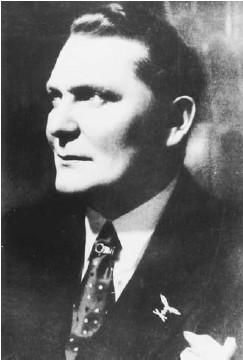

Bruno Loerzer, World War I flying ace and close friend of Hermann Goering. During World War II, he served as the Luftwaffe’s chief personnel officer, commander of the II Air Corps, and chief of personnel armament.

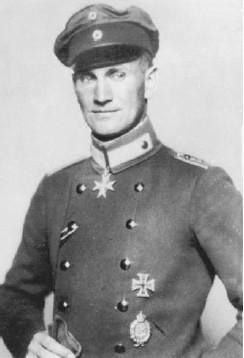

Erich Hartmann as a

Fahnenjunker

.

Lt. Hermann Goering, commander of the 1st (Richthofen) Fighter Wing, during World War I.

A Luftwaffe light mortar crew.

A Luftwaffe light mortar crew.